For some reason, Cavite cuisine has played second fiddle to other regional dishes, including those originating from other Southern Tagalog provinces like Laguna and Batangas, until now. Ige Ramos explains why.

By Alex Y. Vergara

Book designer and food writer Ige Ramos, a true-blue Caviteño from Cavite City, never doubted for once how delicious and varied Cavite cuisine is. The province’s coastal and lowland towns and cities alone have been able to produce a virtual feast of dishes by harnessing and combining the bounties of the sea—from fresh oysters and mussels from Bacoor and Kawit to daing and tuyo from Rosario—with Cavite’s rich agricultural yield.

But for reasons known only to Ige and certain Caviteños, Cavite cooking has always played second fiddle to other regional cuisines, including those originating from other Southern Tagalog provinces like Laguna and Batangas.

“No one had championed Cavite cuisine in the past,” Ige explains. “I also discovered that in places like Cavite City, for instance, the food business is quite sustainable. Our dishes didn’t become known outside the city because we saw no need to sell them to other people. Sa amin pa lang, ubos na (We already have a ready market within our community).”

Proximity to Manila

Cavite’s proximity to Manila, Ige adds, also proved disadvantageous to Cavite cooking. People in Metro Manila, for instance, tended to unwittingly “snub” Caviteño dishes by going further afield to more remote corners of Laguna, Batangas and even Quezon. Although there are plenty of similarities between Cavite cooking and that of, say, Batangas, there are certain nuances that belong solely to the former.

Cavite, for instance, has its own version of Batangas’ bulalo, which Caviteños’ simply call nilagang baka. In lieu of sweet yellow corn, the beef dish, which is basically soup, makes use of starchy white corn, says Ige. Like almost every province in the Philippines, Cavite also has its own version, several, in fact, of adobo.

Achuete, which we all know came from Mexico via the galleon trade, is widely used in Cavite, says Ige. Being a coastal province, Cavite was one of the first provinces in the country that gained access to many of the ingredients and products sourced from all over the world during the Spanish times. One of the dishes the natural red food coloring has spawned is adobong pula.

But Caviteños also know how to adapt and even appropriate a dish from another place by giving it their own take. The province, for instance, also has its version of adobong dilaw, a dish, which, Ige says, originated from neighboring Batangas. It derives its unique color from the use of turmeric or luyang dilaw. But unlike the Batangueño version, which is a bit dry, Caviteños prefer their adobong dilaw a tad “soupier.” And how did such a dish from Batangas end up in Cavite in the first place?

Some like it saucy

“When (Emilio) Aguinaldo remarried during peacetime, his new wife Maria Agoncillo was actually from Taal, Batangas,” says Ige, who researched extensively on the history of Cavite cooking. “She didn’t like the food in Kawit, so she brought with her a coterie of cooks and servants from Batangas. Over the decades, the dish became ‘Cavitized’ because Caviteños want their food masarsa.”

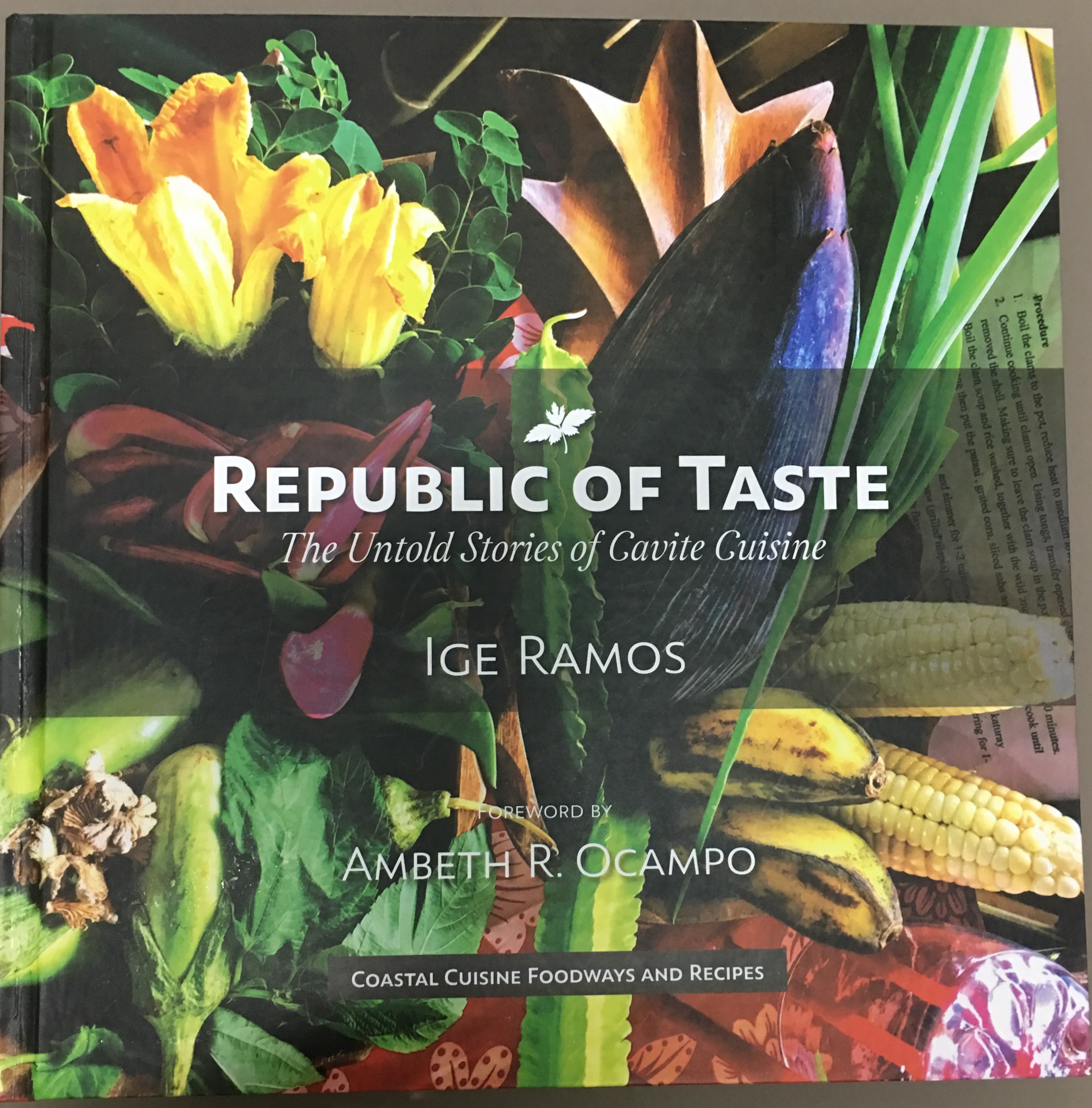

The result of 10 years’ worth of research and interviews Ige conducted, including actually sampling and photographing the dishes from various towns and cities in Cavite before replicating them in his kitchen, is compiled in a handsome 160-page coffee table book dubbed as “Republic of Taste, the Untold Stories of Cavite Cooking.”

Written by Ige himself with foreword by historian Ambeth Ocampo, the book is more than the usual recipe book, as it aims to explain both historically and anecdotally how Cavite cooking came about.

“It’s a recipe book with a backgrounder behind each chapter. There are more than 70 dishes featured in the book,” he says.

Since the province is fairly vast, Ige purposely limited the scope of his research mostly to older, coastal towns and cities, including Bacoor and its Digman halo-halo, Naic, Imus and its famous longganisa and his native Cavite City. Several essays, which introduced certain chapters, were culled from magazine and newspaper articles and columns Ige wrote in the past.

The dishes of Tagaytay, Trece Martires and certain mountain towns such as Maragondon, Amadeo and Alfonso as well as newer ones like Carmona aren’t included in the book. If ever Ige comes out with a follow up to his maiden effort, he might focus more on these towns and cities, he says.

Project collaborators

To realize his vision, he also collaborated with several photographers, mostly colleagues he worked with as editor in chief of Sans Rival, Rustan’s Supermarket’s in-house food magazine, as well as seasoned food editors and longtime friends and fellow Caviteños like restaurateur Sonny Lua.

Lua is the son of the late owners of Asiong’s Restaurant, a must-go-to place in Cavite City. A byword in Cavite cooking, the restaurant has since moved to a quieter, more obscure corner of Silang.

“Since all of us had jobs or were busy during weekdays, we did most our research, which, of course, involved a lot of eating, during weekends,” says Ige. “It was fun, actually. We were like one big barkada bound together by our love for new, delicious finds. Those days were devoted to almost non-stop eating.”

And since it’s a self-published book, Ige, with no publisher to please and commercial considerations to be mindful of (“I’ve invested a good part of my life’s savings in this book,” he shares), finally decided to include Cavite in the title. His initial fears were unfounded. Instead of turning away readers, Ige, to his pleasant surprise, found that there are a good number of non-Caviteños who are genuinely interested in what Cavite has to offer in terms of food.

To make the book truly representative of Cavite cooking, Ige set a number of rules he consistently applied in selecting the dishes to be featured.

First, the dish should be cooked and eaten locally, meaning within the province of Cavite. Second, since the recipes should be doable, the ingredients should also be readily available or easy to source. And, lastly, to prove a dish’s “universality,” at least within the province, at least five people or families from Cavite who don’t know each other should know the dish and how to cook it.

“I had to cook all the dishes that are featured in this book for a good number of reasons,” says Ige. “I had to because it’s a recipe test to know if the recipe really works.”

Ige also needed to know if a dish is doable and as palatable as the one he and his team had sampled in a restaurant, carinderia, or in someone else’s home. When you publish a recipe, he shares, every stage of the cooking should be timed.

“You can’t just pause and cook at your own leisure,” adds Ige. “You have to have an assistant timing you. In a way, it’s like doing a time-and-motion study.”

But by far the hardest part in doing the book, he adds, is getting information, especially the correct and complete version of certain recipes, from people on the ground. After all, you don’t readily share a family’s prized recipe or method of cooking, especially if your livelihood depends on it, with a total stranger.

Before he could obtain some of the recipes and tips from cooks and restaurant owners, says Ige, “I had to engage with them and build a relationship,” over the years. In time, he was able to get quite a number of recipes from people who remember him as a regular diner or suki in their eateries.

Apart from dishes he grew up with in Cavite City like the bacalao made of labahita, Ige discovered a number of new dishes along the way. The talabobo, for instance, a fish dish from Naic has become one of his favorites. The fish is usually garnished with chopped tomatoes, onions and garlic and wrapped in alagao leaves before it’s fried.

“And unlike other provinces,” says Ige, taking a page from his deep and unassailable knowledge of Cavite history. “We didn’t have so-called pagkaing pang mahirap at pang mayaman. This stems from the fact that there was no tradition of haciendero food because we had a proper land reform early on.”

“Republic of Taste, The Untold Stories of Cavite Cuisine” by Ige Ramos is available in hardbound (P1,500) and softbound (P1,000) versions. For inquiries, email ige.ramos@gmail.com or visit the online portal The Kitchen Bookstore.