Despite being on par with Western Europe in terms of attractions, there are two elements that have further enriched and sometimes changed the fortunes of certain towns and cities in Eastern and Central Europe, including Prague, Budapest, Cesky Krumlov and even Berlin: the direct and sometimes lingering effects of World War II and the Cold War.

Text and photos by ALEX Y. VERGARA

Ah, power and its many manifestations and coded messages.

Symbols of power in the West, through elevated and larger-than-life statues of deceased rulers in triumphant poses, from leading an army on horseback to standing astride a chariot, are often in your face and designed to strike awe, even fear. But certain symbols can also be shrouded in layers of subtlety, requiring a trained eye to unwrap hidden meanings behind each element.

Take the case of one of the featured paintings at Schönbrunn Palace in Vienna, one of the biggest and grandest structures in the Austrian capital, which used to be the summer digs of members of the Habsburg monarchy, especially during the reign of Empress Maria Theresa in the mid-18th century.

Set on a series of sprawling French- and British-inspired gardens, which once also featured a mini zoo and botanical garden, the palace itself teems with Rococo and Neoclassical flourishes resulting from the whims of its many occupants as well as the styles that were in vogue over a 160-year period, from Maria Theresa’s time up to Franz Joseph’s reign. As Austria’s longest reigning emperor, he died at Schönbrunn in 1916.

Built in 1896, Budapest’s Heroes’ Square has been the site of important public gatherings among Hungarians for over a century now

One of the best ways to see Budapest’s 11 bridges is to take an hour-long river cruise along the Danube

Designed by Gustave Eiffel, the same architect behind Paris’ Eiffel Tower, this bridge, one of 11 that spans the Danube River, connects the city’s Buda to its Pest side

By 1918, the 390-year-old Habsburg monarchy became history. Soon after, the palace became the property of the newly formed Austrian republic, which eventually turned it into a museum and tourist draw that it has become today. Of its 1,441 rooms, 20 are featured in an hour-long tour focused mainly on the life of Maria Theresa and her 40-year-reign and marriage to Emperor Francis I. Their union produced 16 children, 10 of whom, including the ill-fated Marie Antoinette, survived into adulthood.

Although on the surface, Francis, by virtue of his title as Holy Roman Emperor, was supposed to call the shots, (at least, that was what most commoners were made to believe then) the real power behind the throne was Maria Theresa. Beneath her motherly image, she was a cunning woman who helped expand the boundaries of her empire’s territory without firing a single shot.

Politics is addition

How did she do it? An early adaptor of the age-old maxim that politics is addition, she married off her many daughters to some of Europe’s leading Catholic royals of the day. The move not only expanded the Habsburg family’s territory, making it the second biggest empire in Europe in the 18th century, it consolidated the empire’s grip on power to rival for a time that of Czarist Russia.

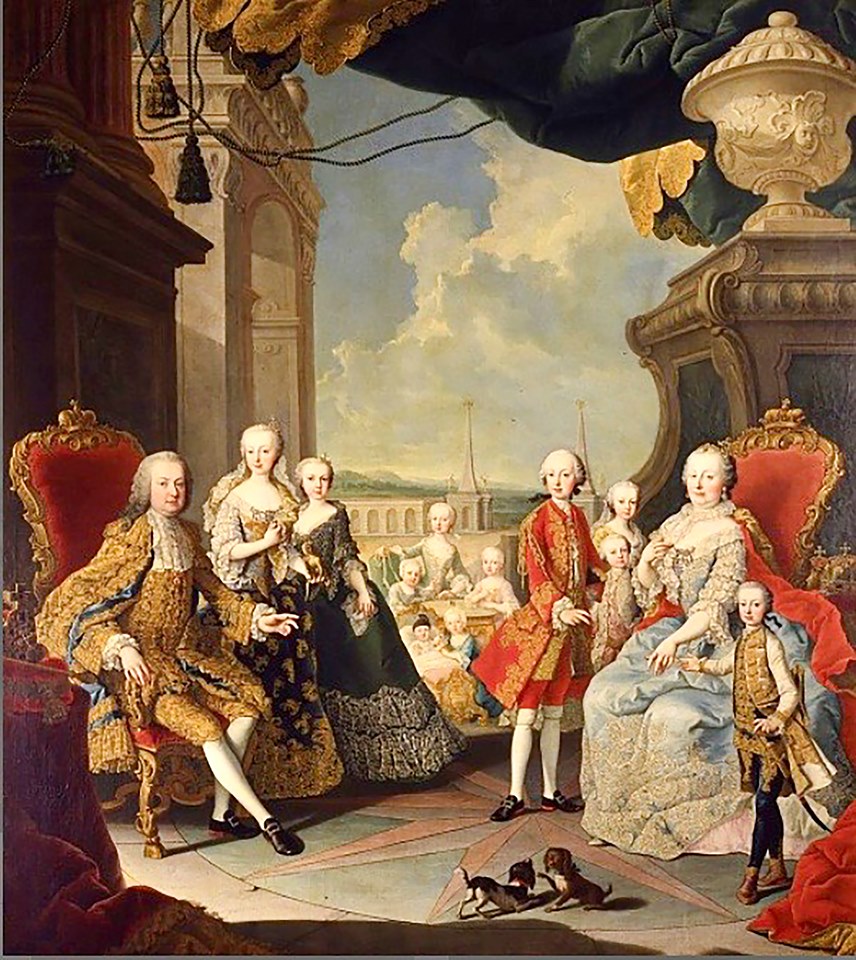

The said painting of the imperial family, which is the focal point of the Schönbrunn Palace tour’s last room, features Francis and Maria Theresa, and their numerous children in what seems like a typical family portrait. At first blush, says our tour guide, there seems to be nothing extraordinary about the painting until you start focusing on a number of telling details.

Prague, capital of the Czech Republic, is arguably one of Eastern Europe’s most charming “walking” cities

“Even illiterate people could decipher these messages,” he says. “Francis and Maria Theresa sit on opposite sides of the canvas, he on the left-hand side, she on the right. While Theresa’s feet and those of her sons rest on a huge star pattern that form part of the floor, Francis and their daughters are either sitting or standing beyond it.”

But the most noteworthy elements that practically tell the world who calls the shots are made by the two principal subjects themselves. Not only is Francis pointing to Maria Theresa, as if telling everyone she’s the boss, the latter is also casually pointing to herself. The only thing missing is Maria Theresa’s talk balloon: “I know, Francis, I know.”

Frequent travelers to Western Europe know for a fact how historically rich and scenic the region is. Those who are fortunate enough to have journeyed through Eastern Europe would come to the same conclusion: the region, despite being lesser-known to the average Filipino tourist, has its fair share of historic plazas and monuments, majestic castles and palaces, magnificent artworks and awesome Gothic and Baroque churches that tower from the ground up as expressions of man’s feeble attempt to pay homage, make sense of the idea and even virtually touch the face of an unseen God.

But there are two elements that, for the most part, are absent in the West that have further enriched and sometimes changed the fortunes of a good number of towns and cities in Eastern and Central Europe: the direct and sometimes lingering effects of World War II and the Cold War.

For 10 days, including travel time from and to Manila, this writer traveled with some of the country’s leading travel executives through fairly familiar (Budapest, Vienna, Prague and Berlin) as well as quaint destinations (Bratislava, Chesky Krumlov, Dresden and Potsdam) this side of the Old World.

Organized by E-WinEr Travel and Tours and dubbed as the “Winner Experience,” the five-country road trip (with scheduled one- and two-night stops in a number of key destinations) through well-paved roads and quiet, postcard-pretty countryside villages, seeks to introduce and showcase Eastern Europe in a different light to today’s Filipinos.

Unlike not a few towns and cities in Eastern Europe, the postcard-pretty Czech town of Cesky Krumlov (above and below) managed to survive World War II and the Cold War, thanks to its rather obscure location

The Soviet bloc

These days, Germany may be very much a part of Western Europe, but at the height of the Cold War, such German cities as Dresden, Potsdam and nearly half of Berlin technically belonged to Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union’s sphere of influence.

If you dig a bit deeper, the region’s history, particularly that of present-day Austria, Hungary and the Czech Republic, is tied to the centuries-long Habsburg monarchy and, much later, its short-lived union with the smaller, less powerful Hungarian monarchy, which gave birth to the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

If our history and geography play a great deal in how we are eventually shaped as individuals, the same thing applies to a particular town or city, especially in a continent as compact and as interdependent as Europe.

Designed by famed German architect Gottfried Semper, the Dresden Opera House was originally built in 1841 before it was rebuilt in 1878 after being damaged by fire

Dresden artwork survives intense heat from bombs dropped on the city during the war

Take the case of the Czech town of Cesky Krumlov. Tethering near the country’s border with Austria and three hours away by bus from Vienna, the little town and its cobbled streets, gabled and brick-roofed houses, Gothic church of St. Vitus and looming castle adorned with frescoed walls seem frozen in time, making it easily one of the most beautiful old towns in Eastern Europe and a leading tourist destination in the Czech Republic, next only to Prague. Now, in a continent with more than its fair share of quaint and charming little settlements, that’s quite an achievement.

And while not a few towns and cities in what was then known as Bohemia were either leveled to the ground by bombs during World War II or later demolished by Czechoslovakia’s Soviet-backed government to make way for drab, space-saving apartment buildings, Cesky Krumlov remains almost unscathed to this day.

“Sans, Souci” or “No, Problem,” an 18th-century palace in Potsdam built by Francophile German king Frederick the Great

Built in the early 20th century following the English Tudor style, the Palace of Cecily in Potsdam, Germany was where Winston Churchill, Joseph Stalin and Harry Truman signed a treaty officially ending World War II.

Even St. Vitus Church, a Gothic structure built in the Medieval period, but teeming with neo-Gothic and Baroque furniture pieces belonging to succeeding centuries, has remained intact in a once devoutly Catholic country where 70 percent of its citizens now describe themselves as atheists. Everything had to do with location, location, location.

“Cesky Krumlov eventually became a town when people started flocking here in the 13th century, right after the castle was built,” said Blanca, one of our many tour guides during the entire trip, referring to the town’s towering and omnipresent castle. “Because it’s far away from Prague and located within the country’s fringes, it was spared from bombs from both sides during the war.”

The country’s socialist government, which came after, didn’t confiscate land and turned houses built on it into apartment blocks patterned after the era’s “socialist” architecture. Again, it wasn’t interested because it considered Cesky Krumlov a remote town.

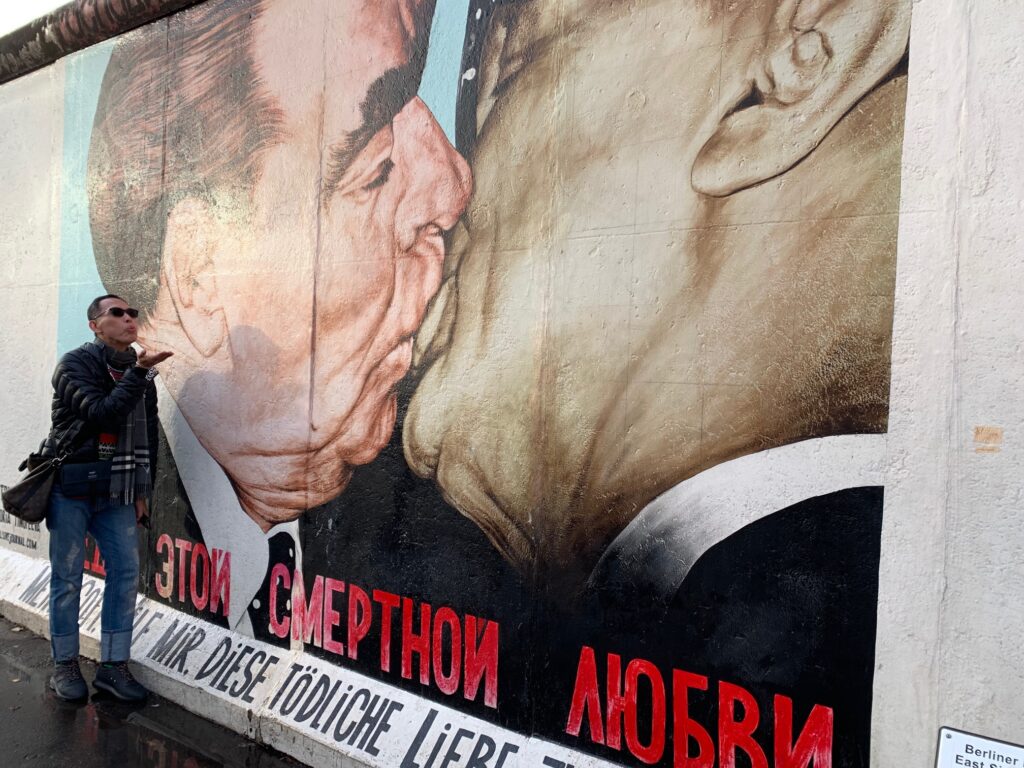

Russian artist Dimitri Vrubel’s “Kiss of Death,” one of many huge outdoor artworks splashed on the walls that once divided East and West Berlin /Photo from Mobisium Market Place

In short, it didn’t offer any strategic importance to anyone—from the Nazis and the Allies, to the country’s socialist government prior to Czechoslovakia’s embrace of democracy in 1989 and its peaceful division between Czech and Slovak Republics soon after. Today’s tourists, all two million of them who visit Cesky Krumlov annually, have this collective apathy from various powers to thank for sparing the lovely town from being erased from the map.

Paris of Eastern Europe

A mere two hours away by bus from Cesky Krumlov is Prague. It’s easy to understand why certain writers have dubbed the city as the “Paris of Eastern Europe.” But unlike the French capital, which is grander and a tad more organized, Prague is smaller in scale and, we dare say, more charming than Paris.

It’s for the most part a walking city, what with its leading attractions such as St. Vitus Church (another Gothic gem dedicated to the Sicilian martyr), Our Lady Victorious Church, Charles Bridge, St. Wenceslas Square and the iconic Prague Astronomical Clock within walking distance of each other.

Boasting of nearly 7,000 towers, spires and various pointy elements, St. Vitus Church was built over a period of five centuries beginning in 1344 and ending in 1929. Wars, changes in leadership and the sheer immensity of the project were to blame.

Set on a hill and built alongside the Prague Castle, St. Vitus Church literally stands out from afar. Perhaps the only church that could rival it in terms of popularity is the relatively newer and smaller Baroque church dedicated to Our Lady Victorious. Within its walls is the diminutive icon of the Holy Infant Jesus of Prague, the inspiration behind the Sto. Niño, making it a must-go-to pilgrimage site for many Filipinos.

As a pedestrian-friendly city, Prague offers a great deal of walking opportunities for tourists. A trip to the city won’t be complete without walking through its 14th century stone bridge named after King Charles of Prague. Boasting of 30 statues of Jesus Christ and the saints, the foot bridge spanning the Vltava River is also a haven for artists, craftsmen and peddlers of various souvenirs.

Finally, if you’re pressed for time and have to choose from the many attractions the city has to offer, a visit to St. Wenceslas Square is a must. Not only is it the site of one of Prague’s biggest Christmas markets during the holiday season, the area hosts the picture-perfect Prague Astronomical Clock, which chimes during certain hours of the day. Every time it does, tourists are rewarded not with the appearance of a giant cuckoo bird, but the emergence of statues representing the 12 Apostles.

If Prague has its Charles Bridge, picturesque Budapest has 11 bridges crossing the Danube River and connecting the city’s Buda side to its Pest side. Two of these bridges designed by the Scottish Adam Clark and Frenchman Gustave Eiffel (yes, the same man behind the Eiffel Tower) are destinations in themselves.

You could either drive over these bridges or sail under them—still, for us, the best way to appreciate these architectural masterpieces consisting of slabs of massive concrete and webs of twisted steel set against a gray autumn sky—during an hour-long river cruise of Budapest.

And if you want a bird’s eye view of the city without stepping inside a helicopter, the best place to soak it all up is by driving to Gellert Hill on the Buda side. Considered as the city’s highest point, the hill, with the Danube River and a number of its more noteworthy bridges and buildings as backdrop, offers plenty of photo opportunities for tourists in a hurry.

Unlike compact Prague, Budapest is more spread out, its wide boulevards lined mostly with attractive buildings that neither follow the Art Nouveau nor Art Deco style. Teeming with a mix of influences perhaps unique to the city—from Neoclassical to Oriental touches, the buildings’ general style, for lack of a better term, is called “eclectical.”

Bridge of spies

Speaking of bridges, the one leading to the small German city of Potsdam, an hour away from Berlin by car, features the famous bridge that figured in the Steven Spielberg movie The Bridge of Spies. Yes, such a bridge, a sight of prisoner exchanges (and most likely plenty of suspense and drama) between NATO and Soviet bloc forces during the Cold War, exists.

Potsdam, which was part of East Germany, may be a small city, but it once hosted a Soviet military base, which explains its importance in German history. During an earlier time, just as World War II was exiting the scene to give way to the Cold War, a palace in Potsdam dedicated to an early 20th century princess named Cecily became witness to another important moment in world history.

Built in the English Tudor style, there’s nothing really spectacular or postcard-pretty about the 180-room palace compared to countless structures of its kind all over the continent. This includes nearby Sans, Souci, which literally means “no problems”—a much older but whimsy-laden palace built by Frederick the Great in 1784 following the Rococo style.

The Palace of Princess Cicely, however, holds the distinction of hosting three World War II leaders—Great Britain’s Winston Churchill, Russia’s Joseph Stalin and America’s Harry Truman—and their respective parties, as they sign a treaty ending the war. The victorious Allies then divided the spoils of war amongst themselves and the countries they represent.

The end of the war soon saw the beginning of another: the Cold War between former allies the US and the newly formed USSR. And these all started in a palace at Potsdam.

In the heart of Saxony

The tour’s German leg started a day earlier with a morning visit to the city of Dresden, the capital of Saxony, a state in the heart of the former East Germany. Apart from its proximity to the city of Meissen, the center of Europe’s porcelain industry, Dresden is known for its magnificent 16th and 17th century Baroque and Rococo architecture, many of which were faithfully restored after being damaged during World War II.

Two of these standout structures are the Catholic Cathedral of the Holy Trinity, a quaint development in itself considering that the city is predominantly Protestant, and the Church of Our Lady, a Lutheran place of worship that’s noteworthy for its visual flourishes.

Who’s the boss? Maria Theresa is pointing right at her. And Franz Joseph can’t agree more.

Despite being a cradle of Lutheran Protestantism (a statue of Martin Luther has a special place of honor in the city square), Dresden is able to hold on to its Catholic heritage because among its many rulers were devout Catholics such as Augustus the Strong and his son Augustus III.

While the father converted to Catholicism to help consolidate his hold on Saxony and its neighboring regions, the son, to his Protestant mother’s dismay, embraced Catholicism with the fervor of a flawed saint.

“Since Augustus III didn’t like bumping into his Protestant subjects, he had a covered overhead walkway built between the palace and the cathedral to avoid them as he went to church,” said our tour guide.

The cathedral’s aisles are also notably wider than most churches and free of any obstructions. How come? To minimize the likelihood of street brawls between Protestants and Catholics, members of the Catholic monarchy held their processions inside the church, which explains the rather wide walkways.

But the nearby Lutheran church wasn’t completely spared either from being influenced by Catholicism. In lieu of a more modest, no-frills altar, the standard look in most Protestant places of worship, is a fairly ornate one typical of Catholic altars save for the missing Corpus Christi on the cross.

Former and present German capital

Finally, the 10-day road trip culminated in Berlin, the once-divided city and the former and present capital of a united Germany. A trip to the city, of course, won’t be complete without stopping at Brandenburg Gate, remnants of the Berlin Wall, which during the height of the Cold War stretched 155 kms. from end to end, and Checkpoint Charlie.

Using prefabricated materials, the seemingly monumental barrier was erected within three short days by the East German government in 1961 to stem the massive flow of East Germans crossing the border to seek asylum in the west.

“When parts of the wall came down in 1989, the German government invited artists from more than 100 countries to turn the remainder into one giant open-air gallery,” our tour guide shared.

Thus, the East Side Gallery was born. And one of its most iconic paintings is “Kiss of Death” by Dimitri Vrubel. Through it, the Russian artist was able to depict the strange, often dysfunctional love affair between East Germany and the USSR through communist leaders Erich Honecker and Leonid Brezhnev locked in a torrid kiss.

During the Cold War, the real dangers lurked before the wall, as East German escapees would have to elude man-made trenches, guard towers armed to the teeth with sensors and machine guns and electrified fences before they could even begin scaling the three-meter barrier. Stretches of the wall even ran parallel to a river laden with booby traps that could easily impale even an Olympic-caliber swimmer.

While countless East Germans died in their quest for freedom, countless others were also able to breathe in the sweet scent of hope, capitalism and democracy on the other side through luck, timing and various ingenious and improvised contraptions—from a family of eight riding a hot-air balloon in the dead of night to a woman fitting into a car’s carved backrest and staying still for hours until the driver, armed with a special permit, was able to make the border crossing from East to West.

All these exploits, including carefully preserved artifacts from the period, are featured in Berlin’s Wall Museum. Indeed, there’s no easy road to freedom, but to a determined soul suffocating under the yoke of communism and tyranny, anything less than freedom is tantamount to death.

The “Winner Experience” group (from left) Ian Kirby Solpico, Marius Cobarrubias, Gerry Concepcion, Ellen Cobarrubias, Cecil Concepcion, Kristine Gonzales, Rolando de Castro, Marl Dupaya, (seated) group leader Erwin Mangaoil, (holding a Philippine flag) the author, Julie Maballo, Glodz Alviar, (seated) Reamaur Bruno Webb, Daisy Ocampo, Marie Yñaga, Ross San Diego, Vicky de Guzman, Catherine Santos, Paulyn Fernando and Irene Binag

For inquiries, contact E-WinEr Travel and Tours at +63 82940088, +63 9178911435 and sales.ewinertravel@gmail.com