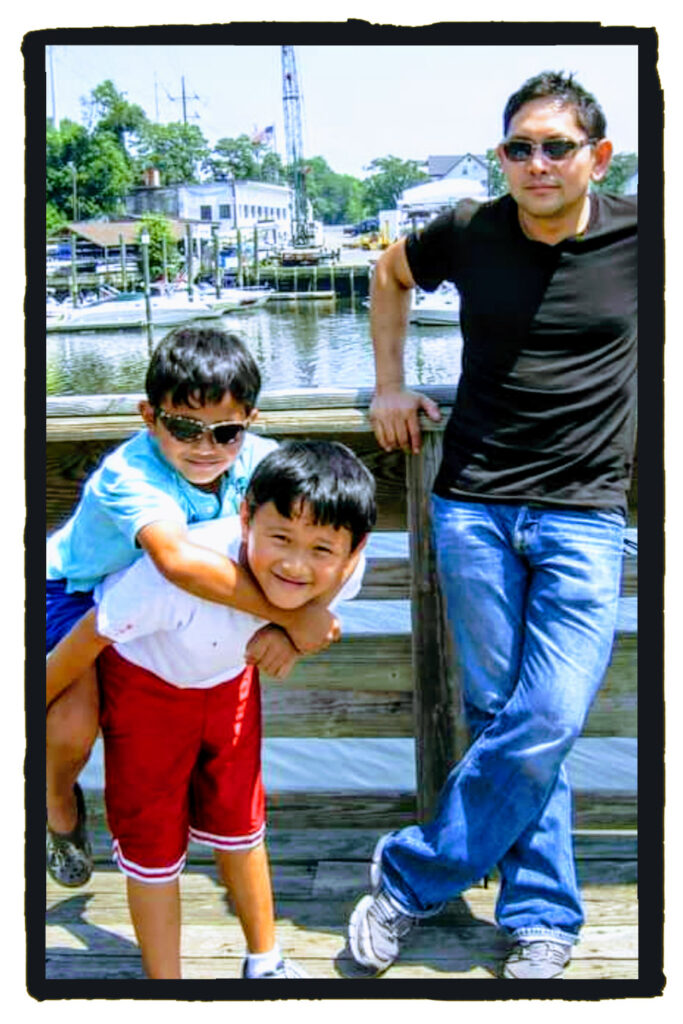

Now that the devastation caused by the coronavirus pandemic is on full display, this US-based Filipino doctor has found new meaning even in his after-work hikes: walking slower, putting more care in taking pictures and savoring the fact that he could still do so. His decision to turn his back on a prestigious career in Boston in 2013 just to be near his two boys in Philly has never been more right.

Text and photos by JAY MOBO, MD, MPH, FACOEM

Last March 12, the day after the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a pandemic, I came face to face shield with SARS-CoV2. I evaluated and tested its human host, a young patient who enjoyed the spring break in Europe the week prior. I was calm. I had been tested fit for such a task. I knew the process that I helped craft, which I had rehearsed over and over in my mind. And I exercised abundance of precautions. The only thing that betrayed my cool was the warm breath fogging the face shield.

I knew that this is what I signed up for. My training and clinical experience dates back to my University of the Philippines College of Medicine days, when I dealt with victims of the 1990 North Luzon earthquake and the 1991 Mount Pinatubo eruption. It continued soon after my graduation, as I attended to doctor-less barangays in Aklan as part of my community project.

My encounters with disease and death proceeded apace when I chose to settle in the United States with HIV/AIDS cases in New York and the 9/11 first responders’ long-term health complications after being exposed directly to both harsh elements and the tragedy of human suffering. These, along with the SARS and H1N1 epidemics during my days at Yale, the local quarantine of a patient ward in a Harvard-affiliated hospital while in Boston and the mumps epidemic in the university last year have, despite my having minimal knowledge about the new viral infection itself, all helped shape my initial response and attitude towards the pandemic.

Thoughts of his sons

And the late Dr. Li Wenliang, the Chinese ophthalmologist in Wuhan who was silenced for being one of the first healthcare professionals in his country to tell the world about the virus, was in my mind, too. Add to those the fact that my two sons go to the same university where I work.

In the ensuing weeks and months, I tried to continuously learn as much about COVID-19 from the US Centers for Disease Control, WHO, peer-reviewed journals, academic symposia, medical grand rounds and through communications with my peers. And since the initial epidemiology and clinical experience had come from the Philippines and neighboring countries, I leaned heavily on my colleagues and classmates back home for advice. Never in my professional life has information changed and been relayed at lightning speed.

The week the WHO declared the pandemic, the university decided early and decisively to go online for the remainder of the spring term. The students and staff in the Tokyo and Rome campuses were recalled back to Philadelphia. By the end of the following week, I picked up my younger son, Christian, to bring him to his mother, as he had to leave his dorm.

His big brother Peter, who was finishing his last semester, wanted to stay in his off-campus apartment. I supported his decision, in large part, because my office is only a couple of blocks away and I could keep an eye on him. But when Philadelphia started to surge in the number of COVID-19 cases and deaths, I strongly advised him to move out of the apartment and to stay with me. By middle of April he moved out.

In my capacity as the university employees’ health physician, my task is to keep the essential employees safe. To this end, I have to identify, test and quarantine symptomatic clinical staff, researchers, law enforcement officers, and the maintenance staff. (The vast majority of the employees have already been working remotely from home.)

Work duties

To date, I have evaluated and tested about 50 symptomatic patients with around a quarter testing positive. The other part of my job is to help ensure the university has adequate staffing, which means I have to monitor the staff who had fallen ill for their safe return to work, as well as to identify and track the co-workers they may have been inadvertently exposed.

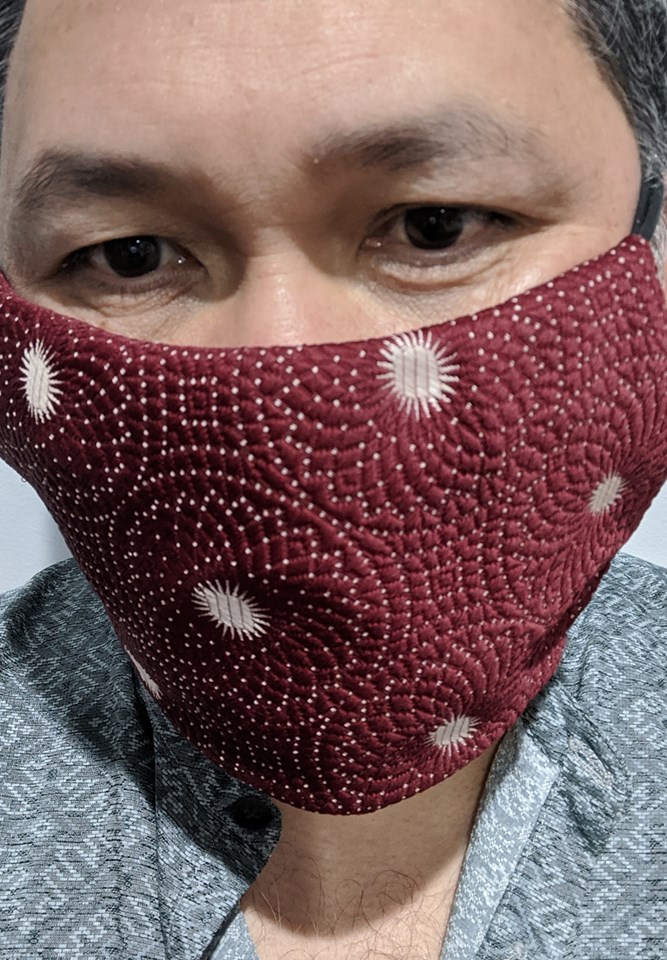

And because recommendations change practically daily based on the latest science, I have to ensure adjustments in my protocols, as well as in the enforcement of the best available safety recommendations (such as universal use of face masks or respirator and regular symptoms monitoring). So far, no one needed to be hospitalized since all have recovered or are recovering nicely, and no workplace transmission among the university essential staff has been documented.

As I also sit in the university biosafety board that oversees research protocols, I make sure provisions for the safety and protection of both the researchers and the human subjects are in place. It’s amazing to witness the unprecedented research collaboration worldwide and the collapse of academic silos, as the best scientific minds rush to understand the mechanism and ramifications of the infection and to develop vaccine and discover treatment, both prophylactic and curative.

From my professional vantage point, I’m also a witness to the generosity of spirit among the staff and students in trying to help out in whatever way they could. A group of students, who were still doing online classes, had volunteered to fabricate 5,000 face shields for the use of hospital healthcare workers. Healthcare workers whose clinics were cancelled had volunteered to set up and man the converted arena into a spill-over step-down hospital. The disastrous Philadelphia experience during the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic more than a hundred years ago must have been instructive on how the city prepared this time around.

On the home front, I, early on, gave my sons a PowerPoint presentation on COVID-19 just because. Since then, we have had discussions about the racial and ethnic harassments stemming from this epidemic among people of color, in particular among those who look like us—Asian-Americans!

We also talked about the disproportionate health impact of COVID-19 on those already marginalized (by race, age, gender and socio-economic status) and on those who have pre-existing conditions, as well as the daunting mental health cost and financial ruins from the pandemic. These concern both of them, but have affected Peter more. He now talks about wanting to be a human rights lawyer. And despite all the pandemonium, or maybe because of it, Christian remains determined to pursue a career in medicine. I gather we will continue to talk about the “new normal” for the foreseeable future.

Finding meaning in everything

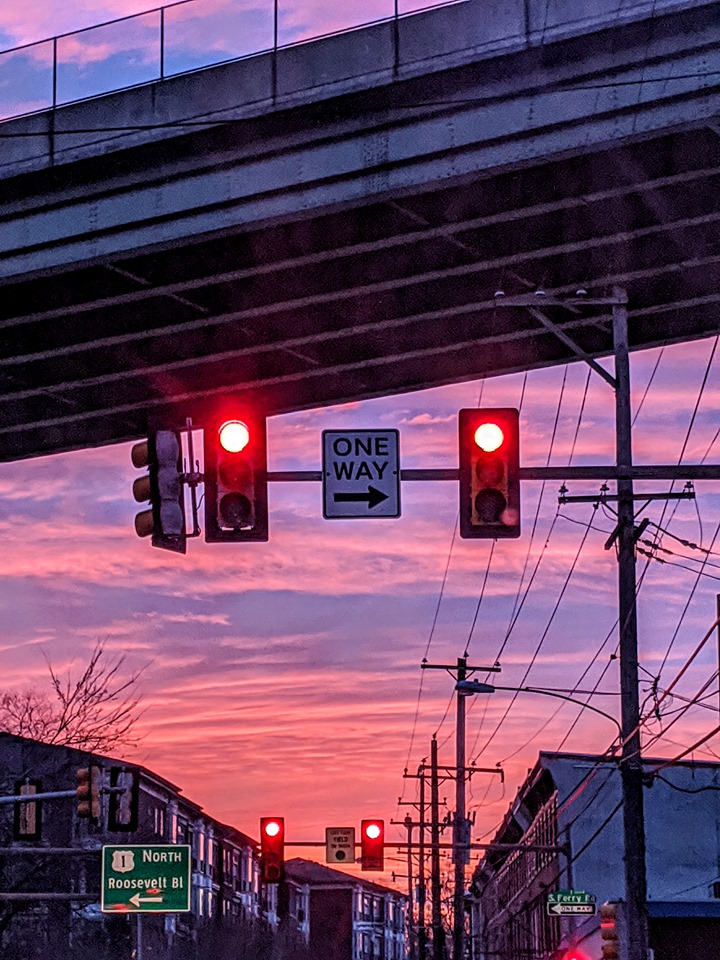

On a personal level, I find starting my mornings playing the video of “The Prayer,” which my mom sent, comforting, even uplifting. On my late dad’s birthday a couple of weeks ago, I fashioned a face mask out of his old wide tie. During my shortened and less frequent after-work hikes, I find myself walking slower, as if trying to savor the simple fact that I could still do so.

I started taking more care in snapping pictures, as if trying to capture more fully the beauty in everyday little things. I once saw a rainbow at the far end of the trail and felt hopeful. I felt the same way when the cherry blossoms finally bloomed and when the Pope celebrated Easter mass alone in a near-empty cathedral.

And on Peter’s supposed graduation day, I took the afternoon off from work to honor his little moment and not-so-little achievement, after all he graduated with honors!

We would have been in Prague and the neighboring places by now to celebrate his graduation. And in mid-June, I would have been in Paris to celebrate Mom’s birthday. Neither is going to happen soon, at least until a safe and effective vaccine or prophylaxis has been developed and made widely available.

Instead, a virus of only about 30,000 base pairs has been weighing down on the world and has utterly upended our collective notion of normalcy. As of this writing, 5,389,949 people have been afflicted worldwide and 343,467 of them have died, including colleagues and fellow frontline workers. To them who had given their last full measure of devotion to serve and protect, they have my utmost respect and admiration.

There’s nothing natural or normal during this pandemic. Yet, I know life still exists and, with it, moments of clarity and joy—however fleeting—co-exist. In one of those lucid moments, I have come to recognize and appreciate this: I left Boston and Harvard in early 2013 to be near my sons following the divorce. I saw it then, as I still see it now, as my paternal duty and moral obligation to be as physically and emotionally present for them as much as possible. I never regretted that decision to leave the highest echelons of the American academia. But this whole pandemic—if there is any upside to it—has made me realize why the decision came too easily.