The lockdown has brought this Brussels-based journalist-turned-chef back to her mother’s table, as she tries to assuage feelings of nostalgia, homesickness, frustration, fear and guilt. Like millions of people, including countless Filipinos now living abroad, seeking refuge at home during this pandemic, she’s using the extra time to push the boundaries of creativity while discovering more about herself every day.

By LOUISE BATERNA

I eat my rice and tuyo with a ripe banana. A strange combination, a strange meal on a spring day in Brussels. It’s not as if I don’t have any other choice or that my pantry is reduced to the barest of essentials. I eat it because it brings me back home. My madeleine of Proust.

The lockdown has unexpectedly brought me back to my mother’s table. It was where the spoiling began. A haven of contentment, where caprices were permitted like eating bananas instead of vegetables. This habit comes from childhood when my mother substituted bananas for vegetables I refused to eat. From the public market, she would pick several hands of señoritas, the sweet miniature variety, half the size of the tasteless cavendish. I would slice it in advance, circles of pulp neatly arranged on my plate. And with each spoonful of rice and fish, a wedge of señorita. Sweet and salty came together in a mouthful.

Mommy thought it was the only way to lure me into eating vegetables. Despite earnest prodding, tantrums flared in front of slimy okras, bitter slices of, well, bitter melon or bland green papayas. Peace would reign when the cook served my mother’s specialties with bananas as a savory ingredient. What a joy it was to scoop saba in Ilonggo dishes such as puchero or humba, chicken and pork stews inspired by the traditional recipes of the peninsulares.

My mother’s table was where much of my happy childhood memories were nurtured. It was the heart of our home, of satiated hungers, of epicurean communions, of sibling squabbles over bangus (milkfish) belly or mango cheeks, which were won by the first who sat before the table. Fortunately, nobody else was interested with my trophies: the tail of a fried fish, the juicy seed of a ripe mango and señorita banana.

I can talk about my mother’s food for hours. But it’s not really her food that I missed.

I miss her.

Emptiness in the time of corona

That emptiness has never been as poignant as it is now in the time of corona. The uncertainty of not seeing her again looms like a kapré (giant tree demon) in my childhood nightmares. I might never see her again and the forced separation makes me sad and afraid. The virus has unilaterally handed out shackles of regret, remorse and a premature mourning for lost time. The physical distance between us has never been so evident, so dramatic. How can it be imaginable when six months ago, it just took an 18-hour flight from Europe to the Philippines to be with her. And yet, on that last homecoming, we fought. I had allowed pride to take over my love for her, thinking that there would be endless opportunities to show her that I truly care. Remorse. And then worries.

My siblings and I are worried sick about her. She’s approaching 84 and still recuperating from a recent major hip surgery. Not only is she diabetic, she also relies on nebulizers every evening to alleviate her breathing. In the face of COVID-19, she’s an ideal candidate to fall victim to the horrible contagion.

Since the lockdown began, my siblings have whisked her away to the family home in Iloilo, far from the city and “hidden” from her usual parade of visitors. Fortunately, one of her yayas has a smartphone. We are connected technologically with her so we can be virtually connected to my mother. These virtual contacts ease the worries, the loneliness.

The online conversations are more animated. I can show Mommy anything, from what I was doing in the kitchen to the flowers in my garden. Sometimes, my daughter peeks in to say hello and that makes her eyes twinkle. I’ve never thought that Facebook Messenger or Skype could be as important as ventilators. These short video calls have become part of my mother’s lifeline.

As to mine, it’s the memory of her generous table.

The virus has plagued even my positive thoughts. So, like the millions of people who have been asked to stay home, I seek cure in comfort food. It seems that the number one activity during the COVID-19 lockdown is eating. Netflix is a mere accessory. Food has reaffirmed its place as the most essential thing during a crisis (toilet paper comes second). It spells survival. And comfort food has become the biggest source of mental security.

Alternative food shopping

When rumors in Brussels spread about a possible lockdown, I avoided the mad rush at mainstream supermarkets. Instead, I went to ethnic shops to stock up even more on what I already had in my cupboards: soya sauce, cane vinegar, noodles, canned sardines and, most importantly, extra kilos of rice. Unashamedly, the hoarding fever got to me, too, so I went to specialty stores to buy flour, bottled vegetables, jams, olive oil and tomato sauce in languages I barely understood: satatka obiadowa (a Polish dinner salad), pan rallado (breadcrumbs in Spanish) or un (flour in Turkish).

This might sound snobbish, but that was my only way to have avoided the crowds and, perhaps, avoided the virus. Besides, in borderless Europe where food trade has created shelves of international offerings, I was simply buying essentials and not luxury products. My pantry became a disarray of cans and bottles, a jumble of origins, except for the absolute mainstay: tuyo in olive oil.

My work as the chef of a diplomatic residence requires me to go out of the house at least two short days a week. There are no events, but my boss insists that I use the downtime to experiment. A recipe a day. And I do, looking for very complicated recipes from renowned chefs that require half a day of concentration, devoid of pressures from producing a perfect plate served at the perfect time.

Work has become a playground and my meticulousness has gained surprisingly fantastic results. That would have been impossible if my time had to be divided preparing three types of gourmet French dishes for at least 30 people, five or six of whom would have had special dietary requirements, the way it was during pre-COVID-19 diplomatic social events.

Back home on non-working days, I’m at my most productive. Though I keep a regular stock of ingredients for Asian dishes, I rarely tackle Philippine cuisine. Yes, I can whip up multiple servings of adobo with my eyes closed, but then, anyone can. Our meals at home are very Belgian.

Taste of home

This is the moment for a culinary reconversion or rather, going back to my culinary roots. And to honor her, I wanted to try my hand on my mother’s recipe of kadyos, baboy at langka (KBL) or pigeon peas, pork and unripe jackfruit. Fortunately, I have a stash of the secret ingredient: batuan, a sour fruit that has travelled from Iloilo’s public market to a Brussels freezer.

Digging from the recesses of my childhood food memories, my heart skipped a beat, as I experienced a sudden craving for my father’s favorite snack: boiled sticky rice mixed with a syrup of coconut milk and muscovado sugar. I was generous with the ginger, just the way he liked it, added a pinch of salt and squeezed a quarter of lime.

My kitchen has taken a nostalgic air. I’m back in the house where I grew up, except that I’m not. I’m in my home away from home of more than 20 years. It’s also full of warmth and love, of disputes and reunions, of giggles and frustrations, but food on the table is something else: 101 ways of preparing potatoes, foul-smelling cheese, beef carbonnade, smoked ham and new vegetables that I have come to like, celeriac and parsnips.

Like my pantry, my vegetable patch is also fusion. From seeds, I planted butternut, zucchinis, leeks and celery and put them side by side with okra, ampalaya, string beans and kadyos. My garden has never been more robust and prettier than it is with extra free time, thanks to the lockdown,

The lockdown reminds me of how lucky I am to have a regular job, where we’re reassured of continuous full pay despite minimal presence at the worksite. In addition, though not perfect, the social security system is reassuring: temporary unemployment is allocated compensation, considerably reduced but the majority of the amount will be paid; health bills are generously covered; and the healthcare system is up and ready in case we’re not able to flatten the curve.

Belgium and the Philippines

What touches me the most are solidarity initiatives from both parts of the world. But unlike in the Philippines where major interventions come from big companies, solidarity in Belgium was born mainly from the grassroots. From free textile and acetate masks to children storytelling via Skype, from online psychological support to love letter-writing for seniors in care homes, from food baskets to clapping our hands for front liners, solidarity actions are expressed differently.

I join the clapping each evening, my thoughts and prayers go to our Filipino nurses and caregivers, especially to one named Flor who was bashed and bullied by members of the Filipino community after the story of her COVID-19 trauma was aired on Philippine TV. She was accused of fabricating a story to get attention. I am furious! Many of us may have settled on new soils, built different lives, reached out to compatriots for fun and company, but sadly, our crab’s claws are ever ready to pinch and pull down, even in times when death from a highly contagious virus is just a breath away.

And during such moments of incredulity and frustration, soon after my anger starts to dissipate, my thoughts slowly turn to my mother’s cooking. And for a few hours, everything is all right again with me in my little corner of the world.

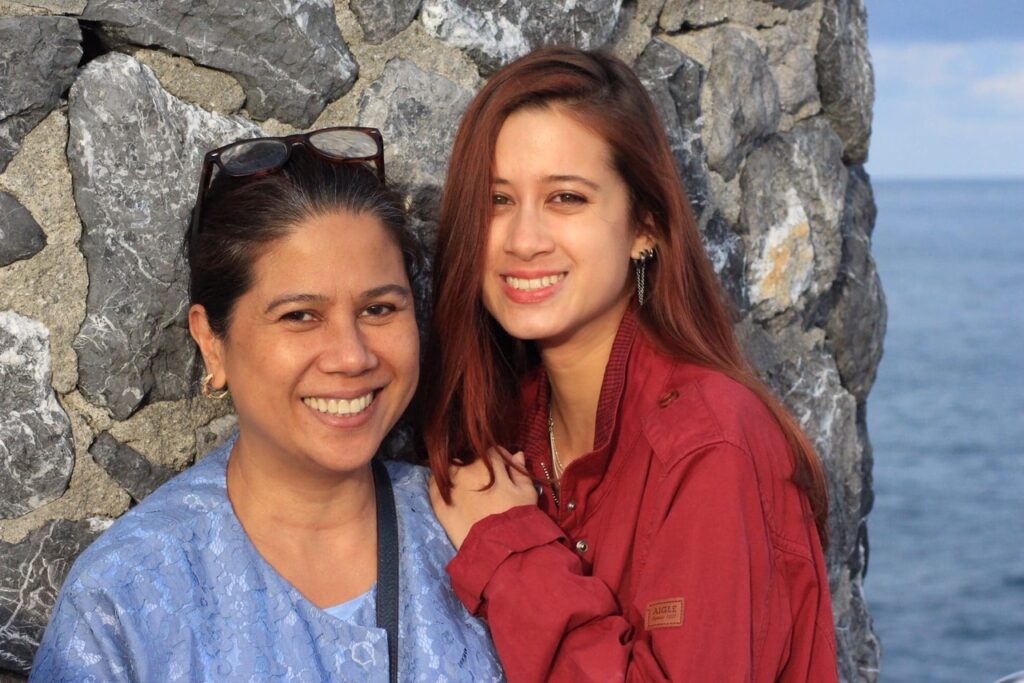

Belgium-based Louise Baterna, a graduate of the University of Santo Tomas, wife to a veteran Belgian broadcast journalist and mother of one, is a writer and former lifestyle journalist in Manila. A woman of many talents and interests, Louise is also an entrepreneur, gourmet and chef who’s equally passionate about her beef carbonnade as she is with her kadyos, baboy at langka.