By Alex Y. Vergara and Jose Paolo S. Dela Cruz

As we celebrate the 36th anniversary of the Edsa People Power Revolution, PeopleAsia readers share their memories of the four-day revolution that toppled a dictator and restored democracy in the Philippines.

People who were either too young or weren’t born yet in February 1986 might think that the abrupt change in government at that time could simply be explained away as the result of a “family feud between the Marcoses and the Aquinos,” as one prominent politician so cynically put it.

Some may ascribe it to a “soft” coup led and supported by the then military establishment. What many seem to forget is this: the historic event, which soon inspired similar peaceful uprisings all over the world, was the culmination of a 14-year struggle by the Filipino people under the yoke of tyranny, oppression, mismanagement and corruption. A long and arduous struggle that began with the declaration of martial law in 1972, leading to the death of our democracy and the birth of People Power, which later saw an overstaying dictator and his family being booted from power more than a decade later.

To those of you who were old enough to remember, where were you during those four brief, heady days in February? As we celebrate the 36th anniversary of the Edsa People Power Revolution, what memories stood out for you as the entire country’s future, as well as our very lives, was on the line?

***

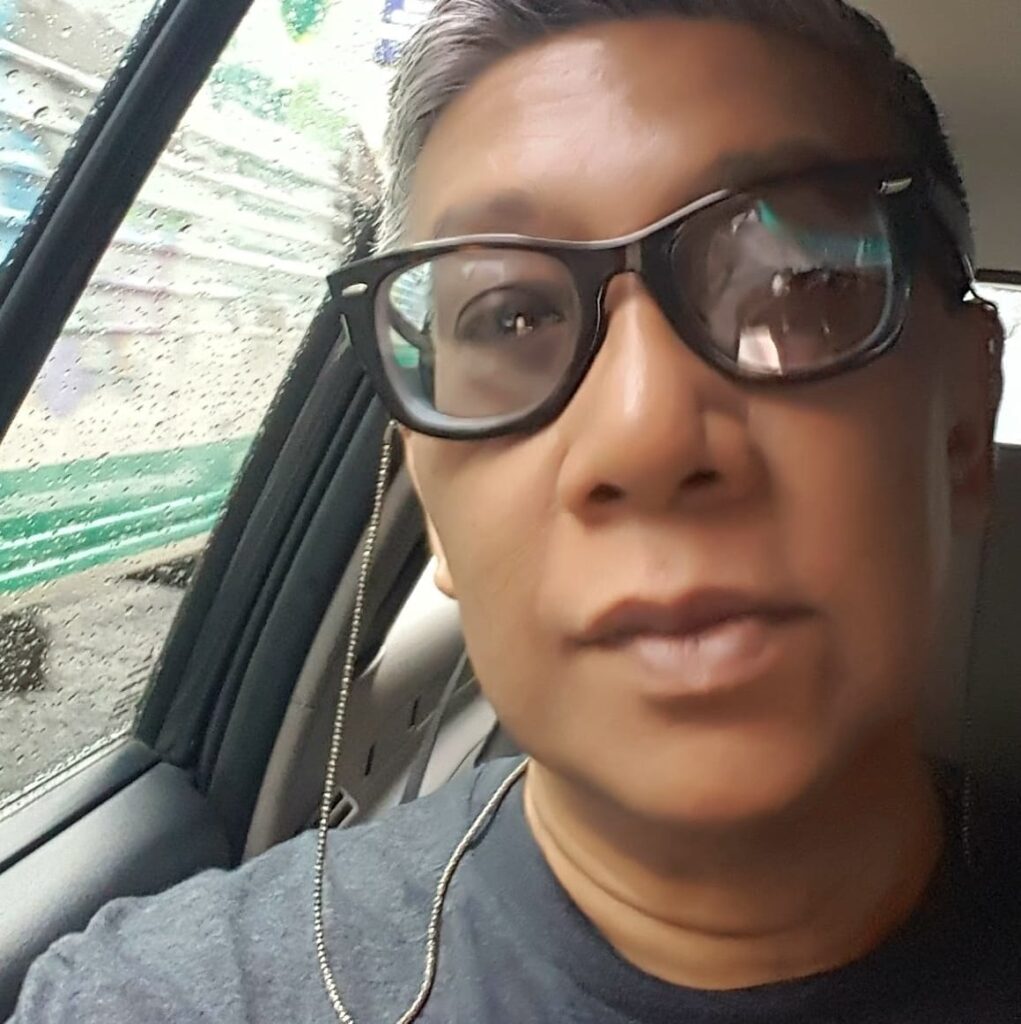

I was six years old at that time. Months before February 1986, I had already joined my parents in countless motorcades and noise barrages all over the metro wearing a yellow shirt and gray joggers. I would usually stand at the back of a pick-up vehicle. The most memorable part for me was how we were flashing the ‘Laban’ sign and shouting the same wherever we went. We thought that if our leaders were disrespecting and dehumanizing us, who else would defend us but ourselves? Glad those days showed “magkaisa” in many forms, to regain our dignity, respect for one another and democracy. — Jeffrey O Tarrayao, president of One Meralco Foundation

I was at home taking care of my three little children (aged seven, five, and two) and was thoroughly scared. Still, I kept on monitoring June Keithley’s broadcasts and also trying to get word about some colleagues at MBS-4, including Menchu Dalusong and Ed Finlan. I think June’s shrill voice was forever etched in my memory, along with an anecdote about another colleague of mine screaming his head off at Ronnie Nathanielz in Malacañan at the time the Marcoses were about to flee. And who could forget Cardinal Sin’s dour voice on the radio appealing to the faithful to rise up, go out and make a stand? —Susan Isorena-Arcega, PR consultant

***

I left the country for Australia the day after I cast my vote for Cory Aquino. Then, all of a sudden, the People Power revolution exploded! I wanted to go back home and join the movement, but all flights to Manila by then were already cancelled. So, I just stayed glued to the TV. Since international broadcasts were uncensored, I believe we got more information on what was really happening on the ground than most people back home. I just couldn’t sit and do nothing, I recall telling myself then. So, together with other Filipinos in Sydney, we organized a mass, which was covered by the Australian media. We also picketed the Philippine consulate in Sydney. I even got interviewed by the local media.—Jomar Fleras, executive director, Rise Against Hunger Philippines

***

I was already in college back then, but my high school friends and I spent our days at Edsa during the revolution, although we got there on Day 2 or Feb 23. We also went to PTV 4 when we heard that they called on the people to help liberate the government station. There, we saw a soldier killed in the tower. His body was tied to a rope and lowered. He was among the handful of casualties in the generally peaceful People Power revolt.

Looking back, my friends and I didn’t consider ourselves heroes. Even to this day, I still feel that way. We went there because that was our chance to stop the dictator from claiming he won the snap elections. We did not want him to steal this one again from the people. So, we were fired up not with a sense of heroism, but with a sense of mission—our generation’s mission—to grab this moment to finally kick out the despot and his greedy family.—Chito dela Vega, veteran journalist and senior editor, Rappler

***

I was a volunteer inside the old Marcos-era Channel 4, now back as ABSCBN. I knew my way around the building because I’ve already been doing shows there since 1984 during my UP college years.

Everyone did their bit to help. No distinction if you were a celebrity or production person. On Day 2 of the revolution, singer Joey Albert stepped in as the floor director, while the other celebrities were doing production work.

One of the perks of fighting for our freedom was the range of good food sent to the studio by various hotels and restaurants — hefty sandwiches from Mario’s and Sheraton. So, amidst the stress and uncertainty, we were, at least, well-fed.

There was a palpable sense of excitement, like some sort of electricity racing through the air, when news broke out that the Marcoses had just left Malacañan. People inside the studio were cheering, crying and hugging each other out of sheer joy and relief.

I remember going home, walking along Quezon Ave, and seeing spontaneous jubilation—drivers honking their horns, strangers smiling at each other and flashing the Laban sign.

As a newbie starting in the business, I was suffused with hope and excitement for what the future holds not only for my industry, but for the entire country. The future was indeed bright. And the succeeding years leading to the next decade proved that. I was able to build a career for myself. Indeed, Edsa, was a turning point in my life. One that I shall never forget.—Eric Pineda, fashion designer

***

We live in Blue Ridge. I remember spending the first night at EDSA. But the next night, we heard word that the tanks were going to take a “back route” through Santolan. To get up to Santolan , they would have to pass through the back route of Libis . Word went out that there needed to be warm bodies on the road up from Libis leading to Santolan.

Libis wasn’t Eastwood then. And the C5 road had yet to be built , along with the cavernous underpass. If EDSA on those nights was busy and alive, the road we were asked to guard was dark, lonely and threatening.

I remember the mood was grim . And the crowd equally grim but determined.

Whispers and hushed exchanges warned of tanks and, worse yet, truckloads merciless marines driving through the passage we were guarding. In the dark, I estimated that we were about 300. If the tanks and the marines were going to come, we were roadkill.

I don’t remember at what time exactly we heard the news that the Marcoses had fled. I remember the the cheers and the embraces . I just wanted to go home. Home was a five-minute walk into the village. I remember my mom and dad were ecstatic and wanted to meet up with the rest of our clan. I just wanted to sleep.—Floy Quintos, award-winning scriptwriter and stage director

***

The first day of the revolution coincided with my political science mid-term exam in UP. At that time, we were still residing in Bicutan, so I always had to leave the house early to make it to my morning classes. Despite leaving early enough for my exam that day, my elder brother (who drove me to school then) and I, were so annoyed with the traffic, which flowed oh-so-slowly—making an already jittery student all the more nervous. Things got worse as we headed further north as we had to be rerouted to take the side-streets to make it to the campus.

Failing to make it to my 10am schedule, I insisted on still coming to school hoping that my prof would give allowances and consideration for the horrendous traffic that I had to go through to make it to class. Noontime came and we were still nowhere near our destination. There were still no cellphones at that time for me to check with other classmates while my brother’s car radio was busted. We had no idea what was going on. By the time our watches said 2 pm, I decided to “give up the fight” and head back home.

Reaching the house close to early evening, we managed to catch the news and understand what actually was going on. The traffic was all because of an ongoing people’s revolution in EDSA, which in just a few more days, won back for the country its democracy. The bad traffic we had to endure was all worth it, after all. And yes, thanks to the delays caused by the revolution, I managed to get extra review time for my exam and got a flat 1.0 for the midterms which, by the way, was also about our reflections on the bloodless movement. — Joee Guilas, director of Communications at Resorts World Manila

***

What I remember vividly during that historic February was the role of media in ending Marcos’ repressive regime. Marcos controlled all media outlets since 1972, but through the heroic acts of a few, truth found its way. On radio, Jaime Cardinal Sin called on his flock to support and defend the renegade troops at Crame and Aguinaldo. We were suspicious at first because we thought it was another of Enrile’s dirty tactics.

June Keithley set up Radyo Bandido after Radio Veritas was shut down. She was reporting in her charming, little girl’s voice what was happening on-ground, from an undisclosed location. That buoyed our spirits, otherwise shaken by the loud whirring choppers circling EDSA. A hard-hitting weekly-turned-daily was churning out prints frequently to capture the deafening dissent against Marcos. Its “Marcos Flees” issue on February 26th was a perfect exclamation point. Courage and integrity in journalism. We must bring that back.–Boboy Consunji, marketing consultant for retail and property