Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in the Philippine STAR’s Feb 25, 2021 issue and on Philstarlife.com.

If the 1986 EDSA people power revolution — the three-day people power revolt that put an end to a 20-year totalitarian regime — were a human being, he/she, at 35, would have settled down by now, no longer a newbie in his/her craft but an expert at it. He/she probably would have already taken off in his/her career, despite the initial baby steps, the hurdles, the setbacks.

However, after 35 years, the EDSA people power revolution, as far as its fruits are concerned, is not quite the mature adult it should have grown up to be. It is not yet a robust success.

And yet, without it, I believe things could have been worse for the Philippines. The country would still be taking baby steps towards democracy, a cherished state for all peoples worldwide, from the recently democracy-tested United States, to Myanmar.

“With EDSA, we made an effort,” my husband Ed, who lived through the First Quarter Storm, marched to Mendiola with my mother in 1986, and held by hand on EDSA, answered when I asked him if EDSA still mattered.

EDSA married the words “people” and “power” in order to spawn change: the restoration of free speech, Congress, freedom of the press, regular elections, and, arguably, a level playing field for all.

EDSA was a template that many freedom movements and marches — from Berlin to Beijing (remember the man who stopped the tanks in Tiananmen Square?), from Poland to the Middle East (the “Arab Spring”) — took inspiration from. A colleague, a millennial, told me, “EDSA and its gains even go beyond the country where it all happened.”

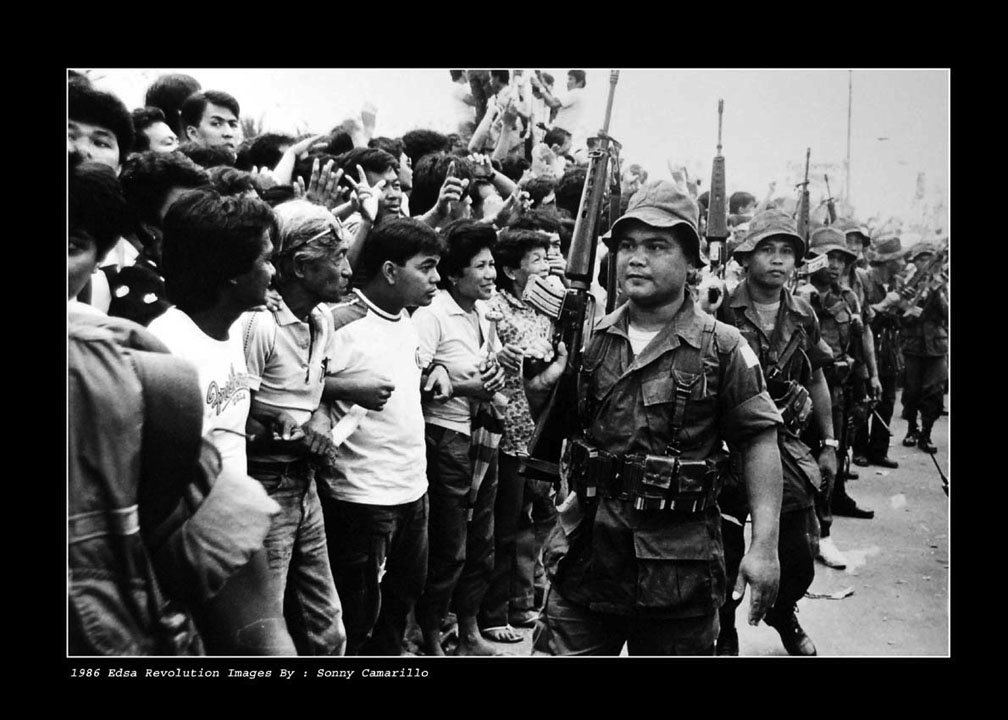

Unarmed nuns, clutching rosaries, stopped gun-carrying soldiers in tanks. Civilians pushed back the tanks, tears in their eyes.

The rich, the poor, they all gathered on EDSA, the former bringing food, enough to feed an army, the latter bringing all they had to lose in the name of freedom and democracy — their very lives.

I choose to honor EDSA. So, this is my EDSA story.

My parents did not discourage their four daughters from attending pro-democracy rallies in the mid-’80s. My husband Ed, then a creative director for advertising firm Bates Alcantara, shared my parents’ political sentiments.

Just before EDSA, he accompanied my mom and my sister Valerie to Mendiola, where they joined the crowd calling for Marcos to step down. They brought home a piece of the barbed wire from the barricades, and that piece of barbed wire is reverently stored in my mother’s Las Piñas home to this day.

But I wasn’t with Ed in Mendiola — because I was heavy with our child Chino, who was born three weeks after EDSA. (He was born on a Sunday, and the centerfold of the newspaper that was brought to my hospital room at the Makati Medical Center had a uniformed Col. Gringo Honasan on it.)

So while my family was on the frontlines, I was busy in another battleground, the Cory Aquino Media Bureau, set up in the Jose Cojuangco and Sons building in Makati. Here, we fought the propaganda war against the dictatorship with guts and imagination and some borrowed typewriters.

Like millions of Filipinos, I had reached that point in my life when I wanted to see change and was willing to not just be a “witness” to it, but also a “weapon” to usher it in. So I said, “Count me in.”

Recruited by my UP classmate Isaac Belmonte to help out in the Cory Media Bureau, I reported every day to our headquarters as a volunteer writer and took instructions from Billy Esposo, Popoy Juico, Ed Zialcita, Teddyboy Locsin and Rene Saguisag.

We issued daily press bulletins to compete with those issued by the well-oiled Marcos machinery. (In the beginning, supporters sent us day-old donuts and tuna sandwiches. After EDSA, they sent food in silver chafing dishes, with matching white tablecloth!)

Though I missed Mendiola, I wanted to be counted at EDSA. I was doing it for myself and for my unborn child. When he grew up, I didn’t want him to live in fear of being sent to prison if he disagreed or opposed the powers that be. I wanted him to vote in clean and honest elections wherein his vote would be counted.

I’m sure my doctor would have been horrified then if she knew that I was at EDSA. My concern then was not that I would be injured — I had faith that I wouldn’t — but that there wouldn’t be a nearby toilet when the need arose! I hurdled all obstacles, thankfully.

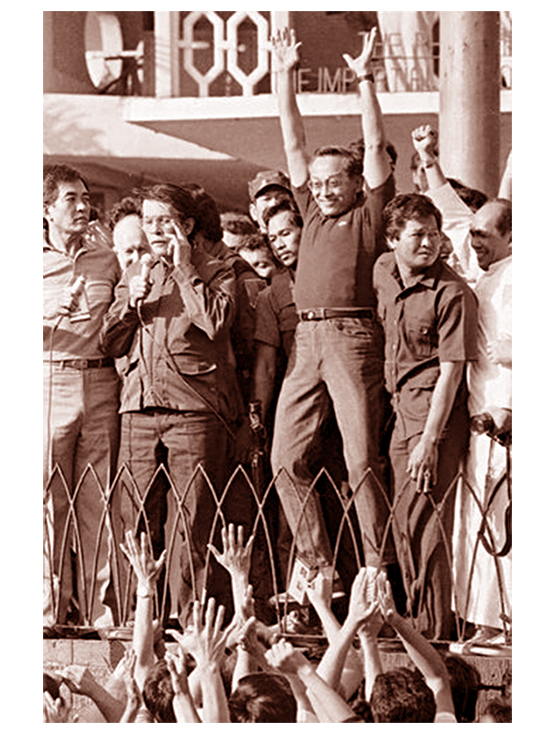

The euphoria I felt when Ferdinand Marcos fled, and the distinction I still feel now at having participated in a moment that changed the course of history, not just Philippine history, made it all worthwhile.

You didn’t go to EDSA with a death wish — you wanted to live more than ever, that’s why you were there — but you were willing to risk your very life for a cause greater than yourself.

EDSA is still a work in progress, and expectedly, disappointment abounds because many are still poor, rights are transgressed, there are documented instances when basic freedoms are not respected. Graft and corruption persist.

But as former President Fidel V. Ramos said in an online interview addressed to millennials, one should not have expected EDSA to serve all the gains of democracy “on a silver platter.”

EDSA shouldn’t be the punching bag for our disappointments for what we have NOT become compared to our Southeast Asian neighbors.

EDSA was a miracle, but the morning after, we should have stopped expecting miracles from it.

So, will people pause and remember those three days in 1986 when the world stood in awe of a peaceful revolution that ended 20 years of totalitarian rule, without blood on the streets?

You don’t have to march on the streets to commemorate EDSA. By marching on to rebuild this country amid this pandemic, using the gains of democracy — honest elections, freedom of the press and speech, among others — we are people, with power. Let’s not waste it.