As the Philippines and Spain celebrate Philippine-Spanish Friendship Day today, June 30, a Spanish journalist and frequent visitor to the Philippines before the pandemic tries to put into context the long shared history between the two nations.

By Jesus Valbuena

On March 2021, 500 years had gone by since the Spanish expedition, led by Ferdinand Magellan, arrived in the archipelago of what is now called the Philippines after 17 months of sailing into the unknown in search of a new route to the Spice Islands (Malaku or the Moluccas).

That first meeting between the East and the West on the islands of Suluan and Homonhon was, in fact, very cordial. The chronicler Pigafetta described the meeting between Magellan and the king of Samar as follows: “… to celebrate a ceremony of our worship. The King approved everything and sent us two recently slaughtered pigs.” Pigafetta was referring to that Easter Sunday, when the first Christian mass was celebrated in what is today the third country with the most number of Catholics in the world. This great adventure, completed by Juan Sebastian Elcano, proved, among other things, the sphericity of the Earth, leading to a redrawing of the world map.

Spanish rule over the Philippine archipelago ─whose name originates from King Philip II─ ended almost four centuries later, when the United States shattered the young nation’s desire for independence and occupied it as its new colonial master during the Disaster of 1898, as this period is referred to in Spanish history books. The Spanish fleet was destroyed by the Americans in May of that year in the naval battle of Cavite and Manila; It was forced to capitulate three months later.

But such news didn’t reach Baler, an isolated town between the northwestern coast of Luzon and the Sierra Madre mountain range. Blinded by hunger, disease and the continuous threats from the Katipunan rebels, the Spanish Expeditionary Hunters Detachment No. 2, made up of three officers, 50 soldiers, and a medical lieutenant and his assistant, locked themselves in the small church of Baler while waiting for reinforcements from Manila, stoically refusing to believe that the twilight of the Spanish Empire on which, for centuries, the sun never set, had in fact taken place in just a few weeks.

Having overcome their agonizing adventure towards unreason for 337 days of confinement in subhuman conditions ─19 soldiers died inside the church─the 33 starving and emaciated survivors, in addition to two Franciscans, finally laid down their arms and left the church on June 2, 1899.

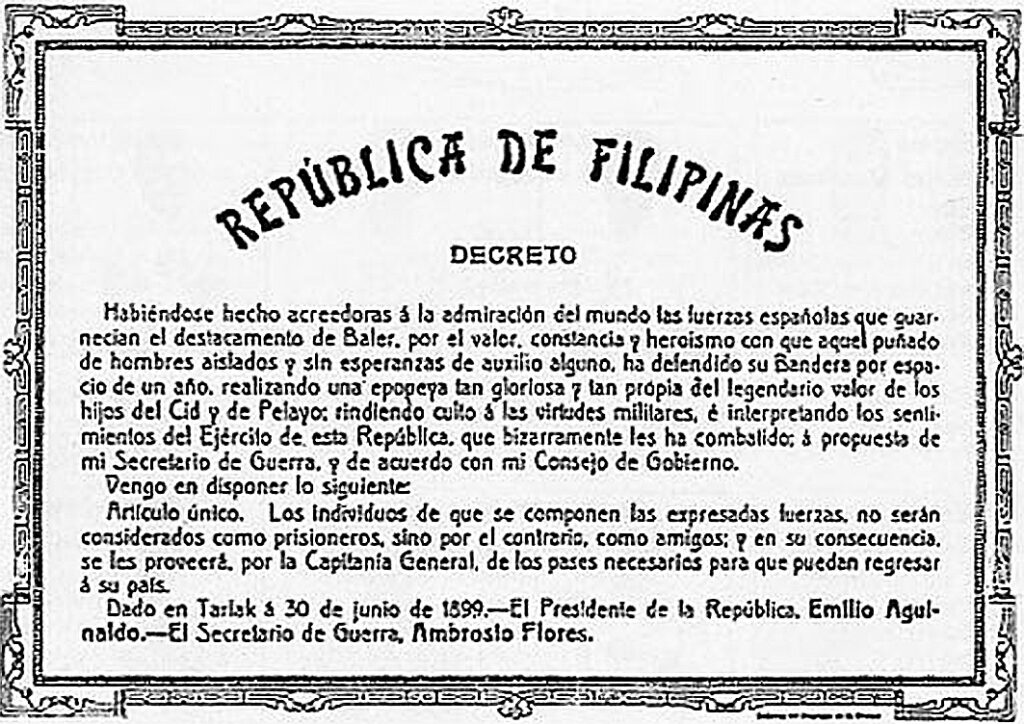

By then, Manila was no longer officially Spanish territory for 10 months. Fearful of possible reprisals from the Katipunan insurgents, it was the leader of the Philippine Revolution himself, Emilio Aguinaldo, who best defined Filipino magnanimity in a famous safe-conduct pass, a noble concession made by victors over the defeated that, during the time, had no precedent in world military historiography.

He decreed that they were to be considered “not as prisoners of war, but as friends.” Aguinaldo added: “… the valor, determination and heroism with which that handful of men, cut off and without any hope of aid, defended their flag over the course of a year, realizing an epic so glorious and worthy of the legendary valor of El Cid and Pelayo.”

Philippine-Spanish Friendship Day

The legacy of the heroes of Baler—better known as the Last of the Philippines—contains a universal code of honor based on imperishable values such as empathy, sense of duty, attachment to life, magnanimity, gratitude, dignity in defeat and humility in victory. This is how the late Sen. Edgardo J. Angara interpreted it in 2002, when he promoted the Law of the Republic No. 9187, which establishes June 30th as Philippine-Spanish Friendship Day to strengthen the relationship between two nations that share so many memories and traditions.

In the words of Sen. Sonny Angara, son of the elder Angara, “we commemorate that what began with death, war and fatality [and] ended in friendship and mutual respect. Instead of commemorating how the colonists surrendered after a siege of 11 months, it is better that, as a nation, we remember that almost four centuries of Spanish rule concluded with reconciliation, friendship, compassion and camaraderie”

.

Both countries now look into the future on the basis of their enormous background of coexistence, with its lights and shadows, like all history worthy of being prolonged for several centuries. The recent inauguration in Madrid of a statue dedicated to the heroes of Baler, located in the same district as the monument that the Spanish capital dedicated in 1996 to the poet José Rizal, the Philippines’ national hero, is another step forward to rescue from oblivion the universal legacy locked in the distant church of San Luis de Tolosa that began during dawn of the 20th century. The documentary The Last of the Philippines. Return to Baler is dedicated to that noble purpose.

***

Based in Madrid, Jesús Valbuena is a well-traveled journalist and communications specialist. He has lived and worked for several firms in the United States, China and the Philippines, where he traveled to Baler for the first time in 1993.

He is the great-grandson of Corporal Jesús García Quijano, the first Spanish soldier who was wounded on June 30, 1898, during the first day of the Siege.

In 2003, he wrote and directed the TV report The Sons of Baler for the Spanish public network TVE. Since then, he has participated in numerous events on Philippine-Spanish relations in a wide variety of media.

In 2004, he promoted the Sisterhood Agreement between the province of Palencia (where Corporal García Quijano was born and buried) and the province of Aurora, an act aimed at developing new areas of collaboration and exchange of experiences.

In 2005, Valbuena was actively engaged with the visit of the Spanish Minister of Defense José Bono to Baler and with the promotion of the first-ever collective homage to “Los últimos” in Barcelona.

That year, he became the recipient of the Cross of Military Merit with white distinction as a recognition for his efforts in fostering stronger Philippine-Spanish ties.

He was also proclaimed Adopted Son of the Municipality of Baler for “serving in his own ways as a bridge towards the continued relations between Spain and the Philippines” and for “his personal capacity to preserve the history of the Siege”.