In November, we remember our friends, loved ones and people we admired and respected that have passed on to the next life. PeopleAsia pays tribute to Max Soliven — one of the founders of The Philippine STAR, and certainly a real blessing to the world of Philippine journalism who will never be forgotten.

By KAP MACEDA AGUILAÂ

It’s hard to believe that a decade has passed since the last By The Way column of The Philippine STAR‘s founding publisher appeared on newsprint – November 24, 2006, to be exact – and we were left to our own devices as he succumbed to a heart attack at the Narita Airport in Japat. Ironically, Soliven was “rushing to board his flight back to Manila,†relates National Artist for Literature F. Sionil Jose.

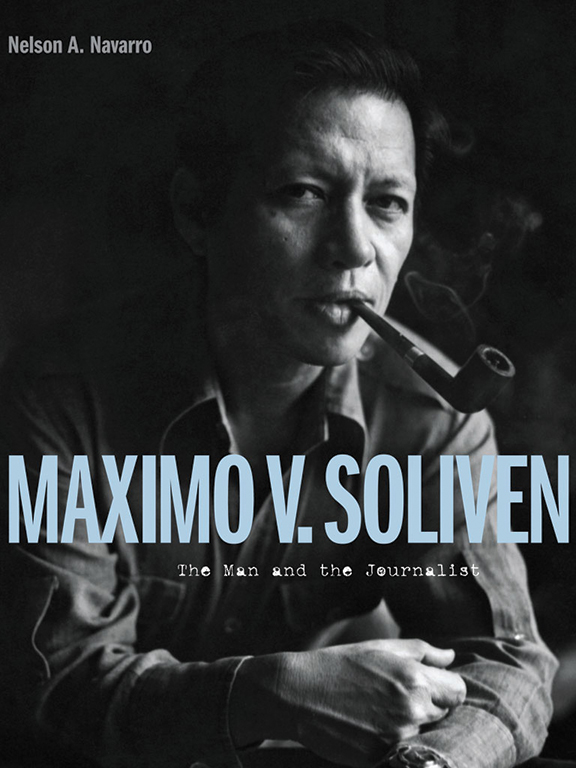

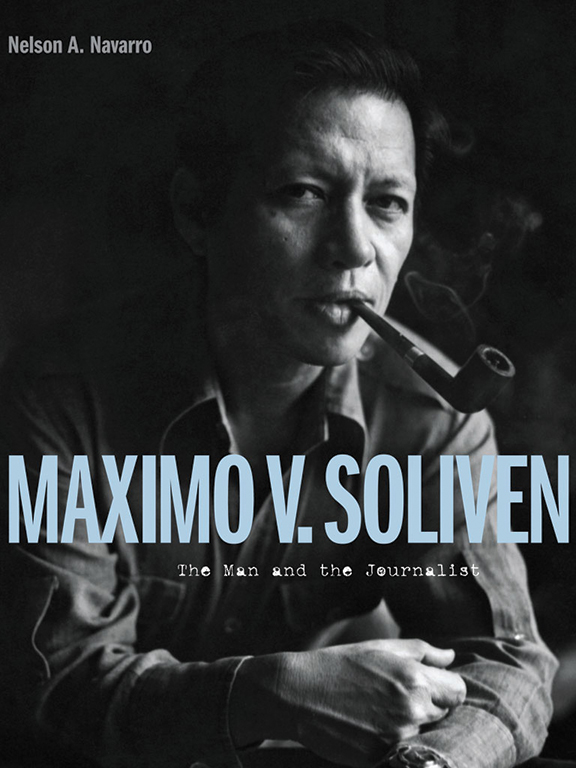

As he described Max in the foreword of Maximo V. Soliven: The Man and the Journalist — a tome penned by Nelson Navarro — “he was an astute writer with an innate grasp of what was important, meaningful but topical.”

Navarro says: “With the passing of Maximo V. Soliven, the Golden Age of Philippines Journalism came to a belated and final close.â€

It is hardly an overstatement. Max Soliven was a true champion of the written word, and he would wield his uncanny mastery over it for almost eight decades. This calling, even at an early age, was something not lost on his beloved father, the late Assemblyman Benito Soliven.

What draws us into Max’s story is that it couldn’t have been better imagined by an accomplished novelist – yet the twists and turns were real. A writer is often called upon to plumb the depths of misery or scale the peaks of pomp and power. But we largely do it vicariously. Even the most skilled non-fiction writer can only hazard a guess at the beauty of a breaking dawn if he himself hasn’t witnessed the lavender, orange and yellow hues beat back the gradients of blue into hasty retreat.

Fate bestowed Max with ultimate lessons of suffering, loss, love and victory. If experience is the greatest teacher, then Max had diplomas aplenty.

He was born, almost appropriately, during a period of great promise and impending tribulation for the country he grew to love so much. As many great men seem to be, Max was, Navarro writes, “in (an) apparent hurry to be born.†Three weeks from full term, Max was first to arrive in a brood of 10 to Ilocanos Benito Soliven and Pelagia Villaflor.

An ode to the father

Max was able to enjoy a charmed life as a politician’s son (among other positions throughout his career, Benito in 1928 won the congressional seat of Ilocos Sur at age 30). There was the privilege of power, to be sure, but the very principled Soliven patriarch never spoiled his kids in it.

Max had said: “Papa could have been President. But more than that, he was a good man with brilliant ideas, he loved our country very passionately and he would’ve been a great President. We could have been a great nation.â€

On Max’s grave at the Libingan Ng Mga Bayani is a quote from the 19thcentury American writer Horatio Alger, one that he held dear from the young age of 12. Max could never forget this piece of inspiring wisdom shared with him by his beloved father: “If I would have my name endure, I’ll write it in the hearts of men.â€

On his deathbed, Benito left his eldest the advice that ultimately steered the course of Max’s career: “If you are thinking of moving into politics some day,†he had said, “my advice to you is not to do so. You are good at writing. Use your skill in the service of God and country.â€

Benito also told Max to spare himself “the heartache and disappointment that come with politics.†That imbued in Max “a sharp distaste for traditional politics but with an even stronger passion to serve the country, in the fashion of Rizal, as a committed writer and journalist.â€

Navarro writes that Max had one hero in his life, and it was his father – and he did the work to do him proud and keep his legacy and way of thinking alive.

Life of the son

Observes Sara Soliven-De Guzman, Max’s youngest daughter: “My papa absorbed Don Benito’s ideas like a sponge, as if by osmosis. The very words they used, the poetry they quoted, the patriotic and religious principles were practically the same, almost like carbon copies.â€

Max was educated at Ateneo (at one time, he was a messenger-errand boy at the Jesuit residence on San Marcelino Street to earn an income). After college, Max, upon encouragement by his mother, sought a college scholarship in the United States. “Max so impressed the (screening) committee that he was awarded, not one, but two scholarships,†writes Navarro.

Max left on the USS President Wilson in August 1951 for a “20-day journey to San Francisco en route to New York via train.†He would start schooling at Fordham University in September. His stint at Fordham and, later, Johns Hopkins University would shape a “US-nurtured political cynicism and hard-nosed view of the world,†even as he stayed true to his own ardent Catholic pride and Marian devotion.

Just like his father, Max abhorred “communism, fascism, and any form of state control.†He would jest: “My politics are to the right of Genghis Khan.â€

Of all the places he traveled to, Vietnam (even before the US debacle there) held a special interest for Max. Perhaps it reminded him of the Philippines, opined Navarro.

Meanwhile, Max’s journalism career continued to blossom. The New York Times, Newsweek, the South China Morning Post, the Bangkok Post — Max had at one time or another acted as correspondent for these.

(In 2000: PeopleAsia founding chairman and publisher Max V. Soliven with the magazine’s current president and publisher Babe Romualdez to his left, and Choy Cojuangco to his right)

When he got back to the Philippines (it was his younger brother Willie’s turn to study abroad), Max tried his hand on a desk job work as a manager even as he arranged a unique “flexi-time†agreement that freed up his afternoons to teach at the Ateneo. For more than a year, he had 18-hour workdays.

But Max’s heart truly lay in journalism. Shunning a lucrative corporate career, he made his way into the local press, working his way up from a beat reporter.

Max once found himself briefing a group of third-year St. Scholastica students on the plant production process of a newspaper. “He was very articulate, very knowledgeable and he answered all our questions. He was so guapo and charming. He was flirtatious and all of us had a crush on him,†said the former Preciosa Silverio – who would one day be Preciosa Soliven.

There are many more stories of Max’s exploits and climb to the top of several newspapers. He was among the founders of The Philippine Daily Inquirer, before he went on in 1986 to open The Philippine Star in a vibrant post-EDSA era.

With all of eight pages and with no advertisements, only a few copies hit the streets. Future STAR president Miguel Belmonte remembers it was a “leap of faith.†But just like its publisher and founder Max Soliven, the STAR – and even PeopleAsia – were not to be taken lightly. To this day they have not been.

By the Way has not appeared for almost six years. That thinking man’s column that featured an “avalanche of data and information, historical context and background†is no more.

Max was, after all, Max – a son of the great Don Benito, for sure – but himself, says his good friend Sionil Jose: “the man and the journalist whom countless Filipinos and other people come to admire or abhor but never ignore.â€

(The original article featuring these excerpts was first featured in PeopleAsia April – May 2012 issue.)Â