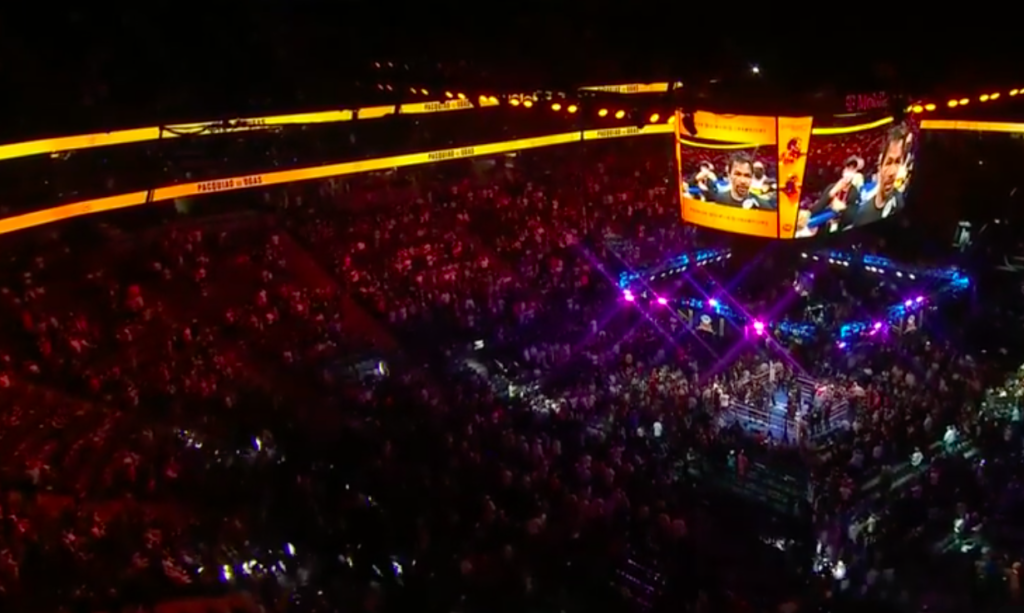

With the entire T-Mobile Arena in Las Vegas chanting his name, this Filipino modern-day gladiator gallantly conceded defeat and declared, “Let’s face another tomorrow.” Losing to Cuban Yordenis Ugas for the (super) welterweight crown, Sen. Manny Pacquiao said with his head high in an interview with sports reporter Heidi Androl :”I did my best. I am sorry we lost tonight but I did my best and I apologize.”

“I want to invite all the fans to watch this fight. It might be my last fight, or there’s more… You’ll never know.” This was eight-division world boxing champion Manny Pacquiao’s response when reporters asked him about his future as a boxing professional at the “Pacquiao vs. Ugas” final press conference last Wednesday in Nevada, Las Vegas.

When Pacquiao climbed the ring at the T-Mobile Arena on Saturday evening (Sunday morning, Manila time), Ugas, the Cuban professional boxer who holds the WBA welterweight title since January 2021, found himself pitted against one of the world’s most prominent sports icons. It is a challenge – and privilege – that the 35 year-old boxer earned, after Pacquiao’ supposed opponent, Errol Spence Jr. backed out of the fight some 10 days ago due to an eye injury. After 12 rounds, Ugas won via unanimous decision.

In his post-fight interviews, Pacquiao said that his legs cost him the belt. “I’m having a hard time in the ring, making adjustments about body style and I think that’s the problem for me because I didn’t make adjustment right away, and also my legs is [sic; tight,” he said.

“It only took me two days to adjust to fighting Ugas. I have fought a lot of right handed fighters before. It would have been harder switching from preparing for a right hander to a southpaw. Most of my opponents have been right-handed, so there’s nothing to worry about,” said the 42 year-old ‘Pacman’ in his recent interviews.

The Boy from GenSan

Stories have been written and told about the days he roamed the streets of Sarangani and General Santos City, looking for anything he could make a buck on. Pacquiao was born to a very poor family on Dec. 17, 1978. He was seven or eight when he felt obligated to help bring food to the table. He brought fish to the market, sold bread, doughnuts, refreshments on the streets. “I also sold popsicles when I was young,” Pacquiao said some time ago, during one of his rare unguarded moments as a superstar.

The problem then, he recalled, was that too many of them sold the frozen snack in their community. “So, I walked as far as I could, every day, to places where I was the only one selling them. I always went home with an empty box,” Pacquiao said. His eyes beamed with pride as he shared his story. “Diskarte (tactic),” he said. Pacquiao also tried to be a good student in elementary in General Santos City. But because of poverty, he eventually dropped out. Again, as a child, Pacquiao had dreams of having an entire buffet table lined up before his family.

In real life, they never had enough to eat.

Pacquiao was eventually introduced to boxing, and he found a better or easier way to earn. Against his mother’s will, he boxed his way around town. In one of his first fights, he earned the equivalent of $2.

When he turned 14, Pacquiao couldn’t take it anymore; he decided it was time to leave the province. By then, his parents had separated. All he wanted to do was give his mother and siblings a better life.

Earlier rounds

In 1995, as a 17-year-old who weighed no more than a hundred pounds, he turned professional, winning his debut fight against a fighter named Enting Ignacio. The fight was held in Mindoro Occidental.

Pacquiao fought everybody thrown in front of him. His style, aggressive and at times reckless, endeared him to boxing fans. He started to gain a following.

He flew overseas for the first time on May 18, 1998 and scored a first-round knockout on Shin Terao at the Korakuen Hall in Tokyo. The Japanese went down three times. That earned him a crack at the WBC flyweight title, and it came just seven months later, against Thailand’s Chatchai Sasakul in Phuttamonthon just west of Bangkok.

Again, the 20-year-old Pacquiao stunned the hometown crowd, knocking out the Thai warrior inside eight rounds. Finally, Pacquiao became a world champion.

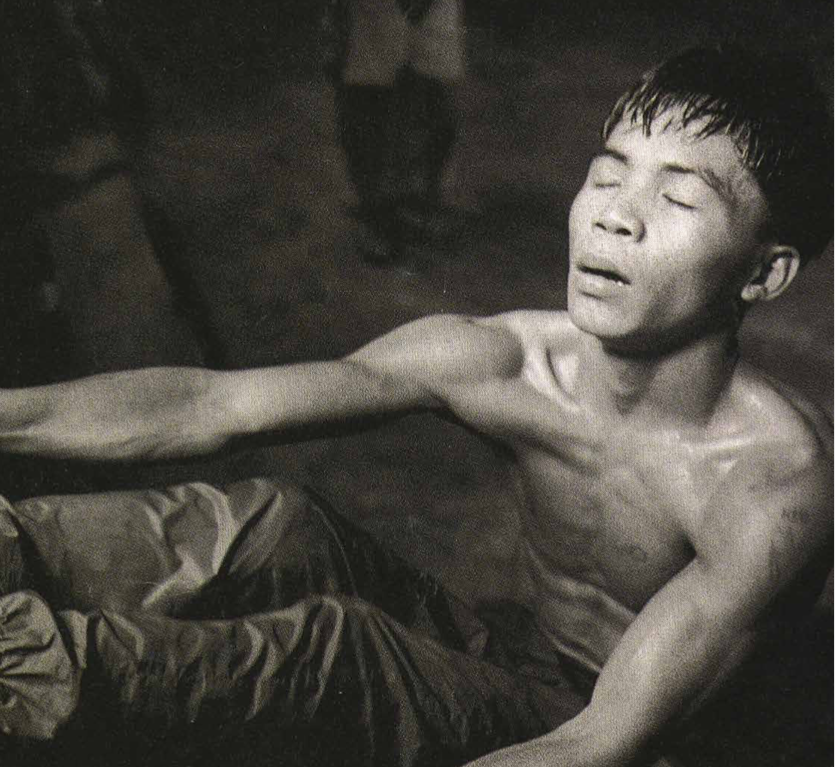

But it all came to a screeching halt in September 1999 when Pacquiao had trouble making weight against another Thai boxer, Medgoen Singsurat. Pacquiao stripped his clothes off to make the 112-pound limit but it didn’t work. After losing his title on the scales, he climbed the ring completely dehydrated.

Big break

Then, the big break came along. His handlers, led by the late Rod Nazario, wanted him to train in the United States. And so, they went. The doors to the Wild Card Gym in Los Angeles opened for Pacquiao, and Freddie Roach, the owner and trainer, welcomed him with open arms.

As a late replacement, Pacquiao, who impressed his American trainer the first time they shared the ring, was pitted against South African Lehlohonolo Ledwaba in 2001. It was the first time Pacquiao climbed the ring at the MGM Grand—as an undercard fighter for an Oscar dela Hoya fight.

Again, he produced the same result—a knockout inside six rounds for the IBF super- bantamweight title. Pacquiao earned $40,000 for the Ledwaba fight. But it was just the start of something big, because soon after, he was bound to make millions.

The world started to recognize Pacquiao as a true world champion. Back home, he became an instant superstar. The former street vendor got used to traveling to the United States and facing tougher opponents like Agapito Sanchez, Jorge Julio and Emmanuel Lucero.

Just after the Ledwaba fight, Pacquiao dropped by The Philippine STAR office, on board a run-down L300 van. The next time he came, for the newspaper’s anniversary party a couple of years back, he arrived in a brand new Hummer, with motorcycle police escorts.

In November 2003, he was pitted against Mexican star Marco Antonio Barrera in the “Battle of Alamodome” in San Antonio. No one from outside his small circle gave Pacquiao a chance to win this one. But he did. Again, by knockout.

Bigger fights then came one after the other, and his earnings grew beyond expectations. For the Barrera fight, he earned $500,000, to be followed by the spectacular draw against Juan Manuel Marquez, netting him an even bigger purse.

The trilogy with Mexican legend Erik Morales came along, and by this time, Pacquiao had built his first mansion in General Santos City and gave his mother and siblings homes of their own. He also reunited with his father. It was a dream come true for the Pacquiaos.

The “Dream Match” with De La Hoya took place in 2008, and Pacquiao, the underdog, turned it into a mismatch. He earned over $15 million for this fight alone.

Next came Ricky Hatton, who was knocked out inside two rounds; Miguel Cotto, who also did not last the distance; and Antonio Margarito, who left the ring with his face bloody and distorted.

Pacquiao fought Marquez a couple more times, and lost one by knockout. He faced Tim Bradley twice, losing once, and just recently he sent Chris Algieri down on the canvas six times for a clear verdict.

Many times, Pacquiao has been asked which among his fights he treasures most. “It’s hard to pick one because all of them are special to me,” he said. “But if there are fights I like most, then they’re the first Barrera fight, then De La Hoya and then Hatton.”

‘Pacquiao for president?’

Despite routinely notching up world boxing titles as if he were picking them off a supermarket shelf, politics has presented a completely different sort of challenge for Pacquiao – at least in the beginning. Here he has always had to punch well above his weight, as he discovered when suffering his first knockout in the political ring.

That defeat for the congressional seat of his hometown of General Santos City in the politically volatile region of Mindanao to demure Rep. Darlene Custodio in 2010 taught Pacquiao a harsh lesson that success and adulation in the sporting amphitheater does not always transfer seamlessly onto the political stage. But suitably chastened, he exchanged his swashbuckling celebrity persona for a voter-friendly and more focused image and won a seat in Congress three years later.

Today, Pacquiao is now part of the Senate, after having successfully amassed 16 million votes in the 2016 elections. And if the rumors hold water, Pacqiuao – after his fight with Ugas – could very well be headed to the biggest bout of his life. A fight that could eventually end up in Malacañang.

And while Pacquiao himself has not yet confirmed his plans for 2022, his spokesperson, Monico Puentevella, says otherwise. “Bahala na kung sinong [ibang] tatakbo (It doesn’t matter who else are running) but Manny Pacman Pacquiao is going to run for President… he will file his candidacy,” Puentevella told CNN Philippines earlier this year.

But the battle for the presidency will have to wait another day. As the STAR’s Abac Cordero wrote in his column last Aug.20, “So close to the fight, there’s no room for politics for Pacquiao.”— by Jose Paolo dela Cruz, with Abac Cordero and Glenn Gale