Born and raised in the Philippines and now living in the US, the author has always been proud and cognizant of the fact that America, for him, apart from being a land of opportunity, is generally a color-blind society where hard work and intellectual merit are all you need to get ahead in life. More recent turn of events have made him revisit such thoughts.

Text and photos by Jay Mobo

On May 25, 2020, Memorial Day, I walked the Cynwyd Trail after dropping off my sons at their mom’s. A wildflower with white petals and a yellow center — an aster — caught my attention. The ring of slender petals reminded me of the coronavirus. The satellite buds, one near the top, the other near the bottom, seemed to suggest yin and yang. To me, the image symbolized purity and balance amidst the COVID-19 pandemic.

After a couple of months under lockdown, Philadelphia was starting to ease off on restrictions. I wouldn’t have imagined that such semblance of fragile peace would be shattered two hours, eight minutes and some 46 seconds later, as harrowing images captured on someone’s smartphone five states away were beamed to the rest of the country, and later the world, almost in real time.

That day in Minnesota, a black man drew his last agonizing breath while a cop’s knee was pressed on his neck. This wasn’t the first brutal killing I’ve been aware of while in the US. But, like many throughout the world, George Floyd’s death on live television provoked something visceral in me.

An America in chaos?

That weekend, more than 100 protests, rallies, and vigils were held across the country, including in Philadelphia. While many of the legitimate protest marches were peaceful, some were marred by violence perpetrated by opportunists who, wittingly or not, hijacked the agenda of people expressing righteous indignation. Visuals of burning police cars and looting sent a message to the world that America is in chaos.

Back in the Philippines, I grew up during the Martial Law years and have heard stories of arrests and incarcerations of protesters in my childhood. But my first real exposure to social injustice was while at the Philippine Science High School or Pisay on August 21, 1983—the day Ninoy Aquino’s lifeless body, felled by an assassin’s bullet, lay sprawled on the airport tarmac.

During college, I joined the first batch of UP students in EDSA. And I fully understood and recognized early on the great divide between rich Filipinos and those struggling from paycheck-to-paycheck. After all, Pisay and UP were microcosms of the country. I was aware that many of my friends have wealthy parents. But that didn’t matter. All that mattered was your hard work and dedication to learning. So, I would like to think that I have a healthy sense of social justice and equality. But racism wasn’t something I was aware of.

A person of color

Even in the US, I haven’t experienced racial discrimination towards me personally (at least not to my face). Intellectually, I am cognizant of the impact of race and socio-economic factors on health. But my America was proud and nurturing of its diversity and talent.

My mentor at Montefiore is of Irish Catholic descent, who married an Indian woman. Tom introduced me and my now ex-wife to their priest, Father Ned, who officiated our wedding. Interestingly, Father Ned had been to Boracay while visiting his brother, who is another Jesuit priest assigned in Ateneo.

My best friend at Yale is Nigerian-born. He now heads the 3M global medical department. Mark, my renowned program director, is Jewish. He left Yale for Stanford because his wife was offered something she could build from the ground and shape into her liking. Mark handpicked me to take over his Master of Public Health course and elevated me to associate residency director. He was replaced by Carrie, another renowned occupational pulmonologist. And more than half of the Beth Israel Deaconess healthcare quality and safety leadership was female.

My piece of the American pie was also sweet, kind, and generous. It was rewarding of hard work and merit. I would like to believe that my America had been colorblind as evidenced by my personal and professional growth. My little piece of America led me to the hallowed halls of Yale and Harvard despite of my brown skin, peculiar accent, and foreign education. Ultimately, then, the America that I knew allowed me to come to Philadelphia to be near my sons by providing me job opportunities based solely on my skill sets.

On June 4th, several days after a weekend of violent protests in Center City, Philadelphia, I brought my eldest son, Peter, to his allergy clinic for an overdue follow up. The clinic is about a block from city hall. On the way, we saw blocked-off streets and a troop of fully armed police and military personnel guarding the front of city hall. I asked Peter if it scared him. He replied with a nonchalant no. I know that he and Christian, his younger brother, are aware of racial injustice and discriminations from school.

And we had had recent talks about the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on people of color. So, to me, his reply came from a place of his truth and experience rather than from indifference. When they were younger, we lived in the smallest house in the tony town of Darien, Connecticut. Peter and Christian were among the handful of non-white kids in school. Yet, they were never bullied or ostracized by virtue of the color of their skin. Their cohorts of friends have always been multi-racial. Thus, I would like to think that we had raised them in the mold of my version of America to be colorblind, conscious, fair, decent, and upstanding citizens.

Changing times

Yet, I sensed a change in my America in recent years.

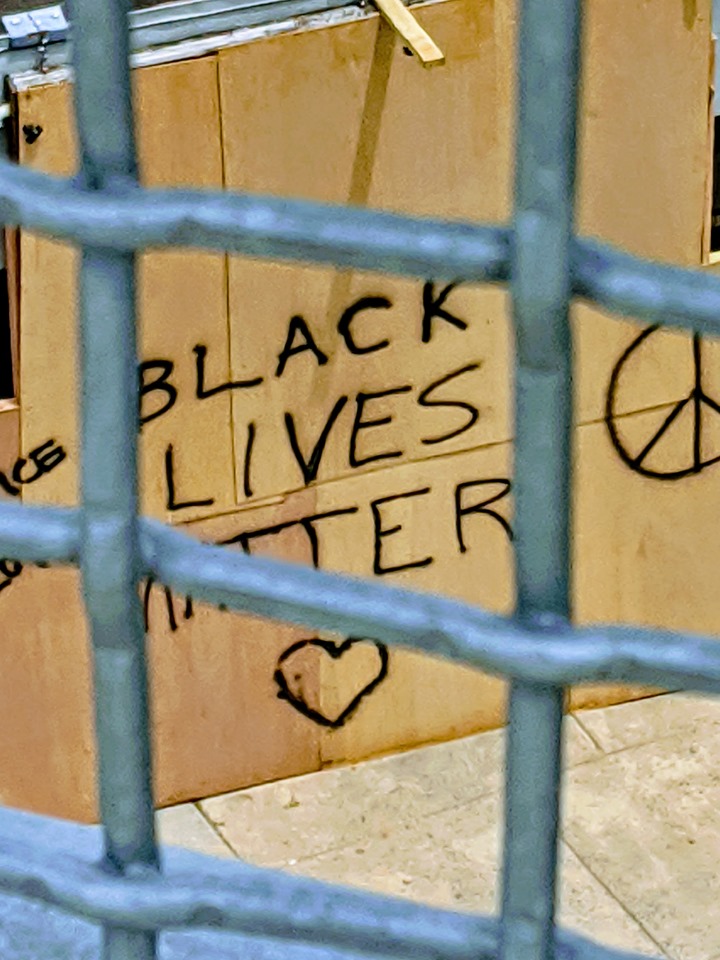

I understand the racial divide between white America and black America is deeply rooted. I cannot even begin to suggest that I understand the full issues. For me, “Black Lives Matter” is predicated on the principle of improving the lives of the most disenfranchised. And, once the floor is raised, so will the rest of the house. Or something along the lines of rising tides and lifting all boats.

Theodor Adorno, a noted German philosopher and sociologist, once said: “Not only is the self entwined in society; it owes society its existence in the most literal sense.” He must have alluded to Vincent Chin, a Chinese-American who was beaten to death by two white men who displaced their anger on him over losing their jobs to Japanese workers.

So while I cannot offer solutions given the limitations of my American experience, I know that we all have a skin in the game. I also know this: A behavior unbecoming when modeled by someone in power gives permission for others to do the same. Vitriol when spouted by people who should know better emboldens and enables more hatefulness. If left unabated, it will permeate and seep wide and deep, and it will corrode everything on its path. Sooner or later, it will hit home. And, then, we all lose: Black, White, Brown, everyone.

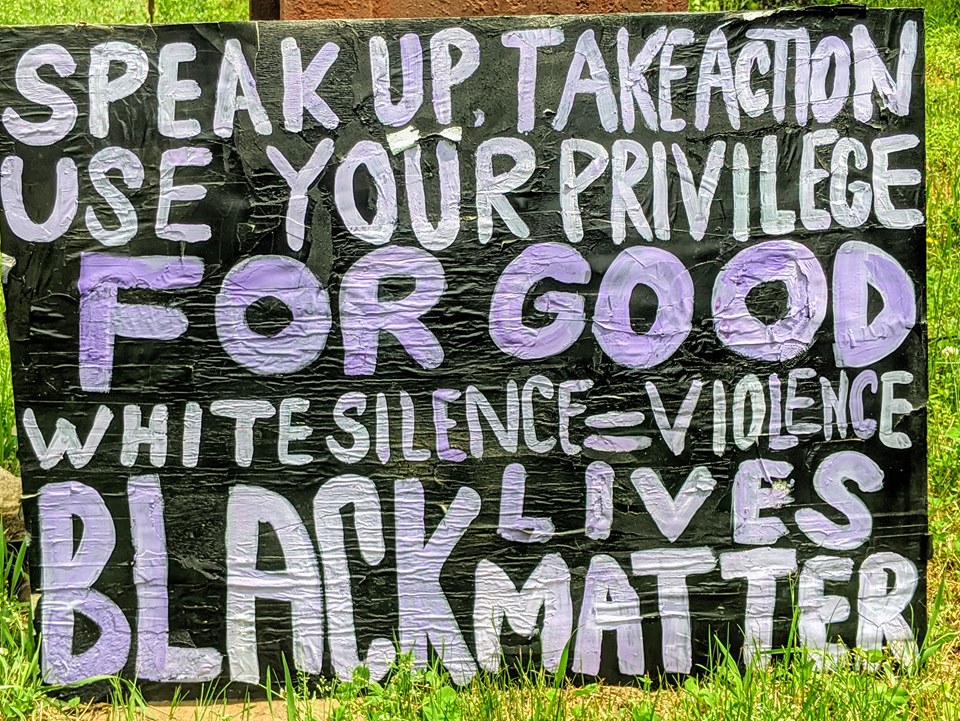

On June 6th, I walked the same trail. Hoisted in one of the posts was a homemade poster that read: “Speak up. Take action. Use your privilege for good. White silence =Violence. Black Lives Matter.” Under the bridge, I heard cars honking. I peeked and saw people of various ages, genders, and colors peacefully holding up signs or kneeling quietly, as passing cars honked in solidarity. The few police officers were standing by to keep the peace.

My mind went back to my aster photo. I checked the image in my phone. Instead of a simple flower, what I saw this time was a satellite image of an eye of the storm. In my mind’s eye, it now symbolizes a storm of change that is coming. Someone wise once said: “The opposite of love is not hate, it’s indifference…And the opposite of life is not death, it’s indifference.”

My version of America has to reconcile with the rest of itself and to heal as one. Then, and no sooner, can we celebrate a true independence.

Dr. Jay Mobo is a father of two young adult sons. He is board-certified in both Internal Medicine and Occupational and Environmental Medicine and received a Master of Public Health at Yale. In his spare time, he likes to dabble in photography and writing.