BY MAX V. SOLIVEN

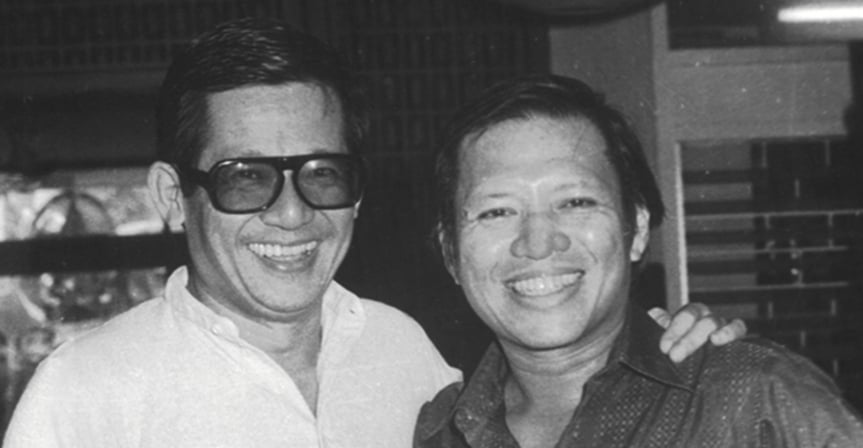

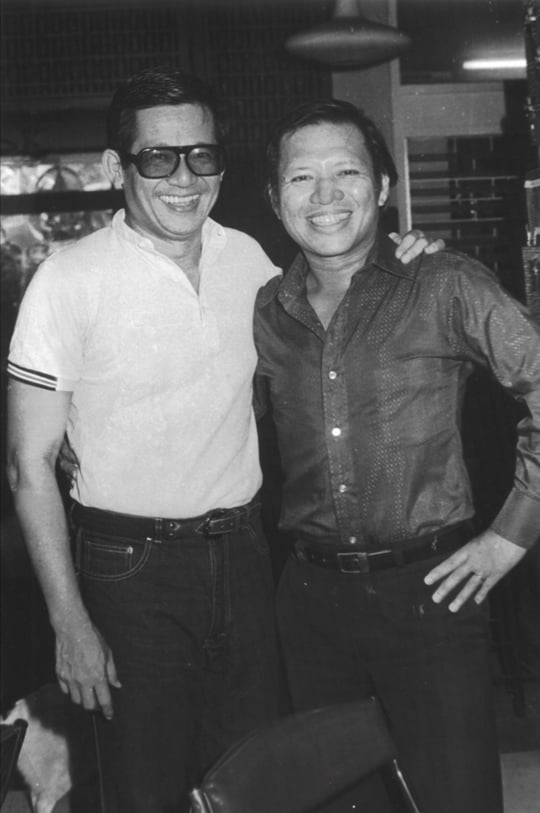

Max V. Soliven was founding publisher of The Philippine STAR as well as PeopleAsia magazine. Soliven and the late Sen. Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino were arrested and thrown into the same prison after martial law was declared on Sept. 21, 1972. On the 38th anniversary of Ninoy’s assassination this Saturday, Aug. 21, read Soliven’s poignant tribute to his martyred friend.

What we have to fear is not any lingering doubt of Ninoy Aquino’s heroism, but its opposite—the danger that he might become a “cult figure” of such rarefied proportions as to appear godlike or superhuman. For, although we dubbed him “Superboy” (both in derision and admiration) early in his career, we knew well enough that he was of flesh and blood: we saw with a jeweler’s eye his doubts, his hesitations, his mercurial swings of mood and his imperfections. And this is precisely what makes his heroism so grand. That he rose over all these blemishes to become – not just in one blinding moment of bravery, but in the slow and painful crucible of imprisonment and humiliation—a true hero.

Starting early

Ninoy Aquino was the son of a landlord and a politician. He was a “premature” baby, his mother, Doña Aurora, said, recalling that she had given birth to Ninoy on Nov. 27, 1932. “I was expecting a delivery in the first week of December and I was very glad because it would coincide with the fiesta of our town of Concepcion, Dec. 8. But I was just as glad over Nov. 27 because it was the Feast of the Miraculous Medal.” His father, Don Benigno—a senator—was in the United States and learned of his son’s “arrival” by a cablegram sent by no less than the American governor-general himself.

Ninoy was Doña Aurora’s second child. The eldest, in what was to become a family of seven kids, was Maur (now Mrs. Ernesto Lichauco) – there were 14 months between Ninoy and her.

Their mother recalls that, from the very start, Ninoy enjoyed being around people. “Filipino children tend to be shy,” she says, “but Ninoy was certainly not. At three, his father would display him to all our visitors and he loved to ask and answer questions. When he was in the shower, dad would send Ninoy out ahead and he would entertain our visitors. When he was four, we sometimes would miss him—and guess where we would find him. In the driveway or at the curb, among the drivers of our guests, talking with them. He was even giving speeches to them.”

Ninoy was no scholar. Maur recounts that he hated to go to school. “Our house on Broadway and St. Joseph’s College was only a block away. And I remember, when we used to go to school. Every morning it was really such a chore because the driver had to carry him to school…” Ninoy was about four or five years old at that time. Later on, he was transferred to the Ateneo Grade School.

Ninoy hopped from one school to another. For high school, he went to San Beda, and acquired that typical Bedan “regular guy” spirit – practical and irrepressible. There was a stint in De La Salle College. Then he went to the Ateneo to study A.B. Philosophy, soon shifting to A.B. History. Finally, he went to the University of the Philippines to study Law.

Ninoy loved the limelight—and he loved girls. And if you couldn’t make the basketball varsity team, or the football team, what was more glamorous than to become a cheerleader? Ninoy tried out for the Ateneo Cheerleading Platoon, and was rejected. Joe Lazaro, who was head cheerleader, remembers that the young Aquino was too clumsy—all arms and legs going the wrong way. But Ninoy gritted his teeth and persevered, practicing those movements many hours a day. In his second year at the Ateneo, he was finally accepted and proudly got his cheerleader’s blues.

And Ninoy did have that fighting spirit himself. His father, previously so revered, was branded a collaborator after the war. His father, whom he worshipped, died of a heart attack on Dec. 20, 1946. Ninoy was 14 years old at the time.

The “Motion Machine”

Somewhere along the line, Ninoy picked himself up and resolved to restore the family name to its former glory. As friend and foe alike were to remark in later years, he was a perpetual “Motion Machine”—restless, searching, almost as irresistible as a force of nature, crackling with suppressed mischief and laughter.

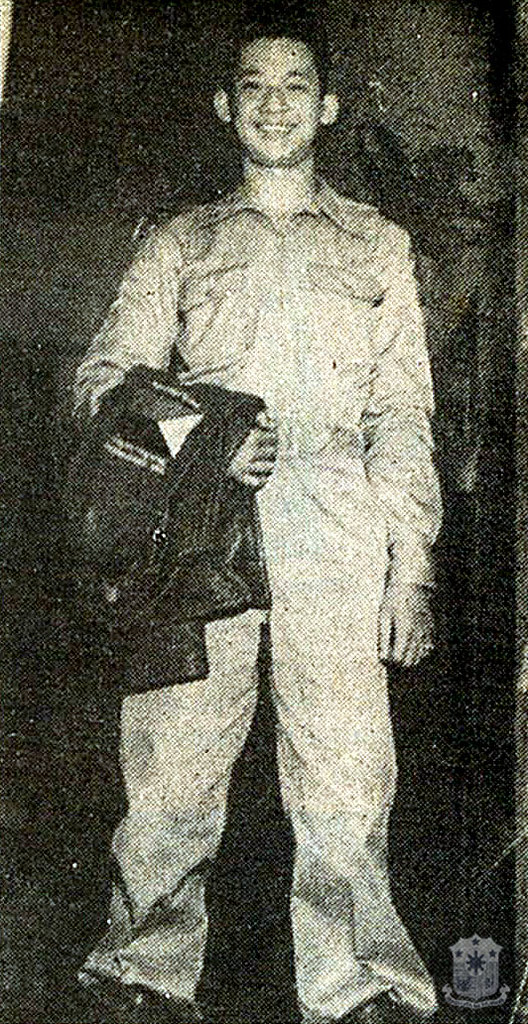

Ninoy went on to join the country’s newspaper, The Manila Times. When The Times was casting about for someone to cover what was happening to the Philippine contingent in the Korean War, Ninoy jumped at the chance. He cajoled the newspaper’s Brooklyn-born editor, Dave Bugoslav, and its publisher, Joaquin “Chino” Roces to send him to Korea. But he was only 17! What could a “boy correspondent” do? When the two hesitated (Chino exclaimed, “What will your mother say?”), Ninoy simply hitched a ride on a military plane and was in Korea, sending dispatches before his two bosses realized that he had jumped the gun on them. The Times’ editors, Bugoslav and Jose Bautista, soon came to appreciate that gung ho quality, which was to rocket Aquino to fame.

Man in a hurry

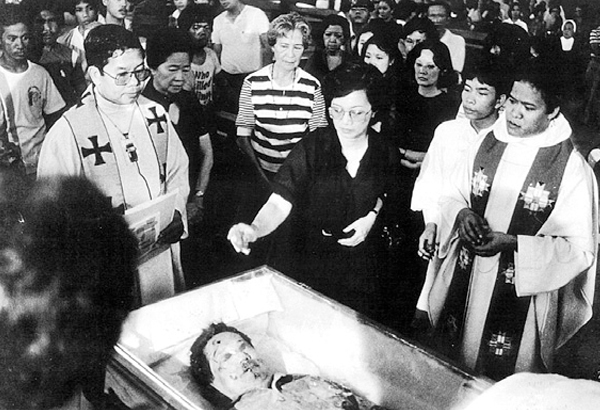

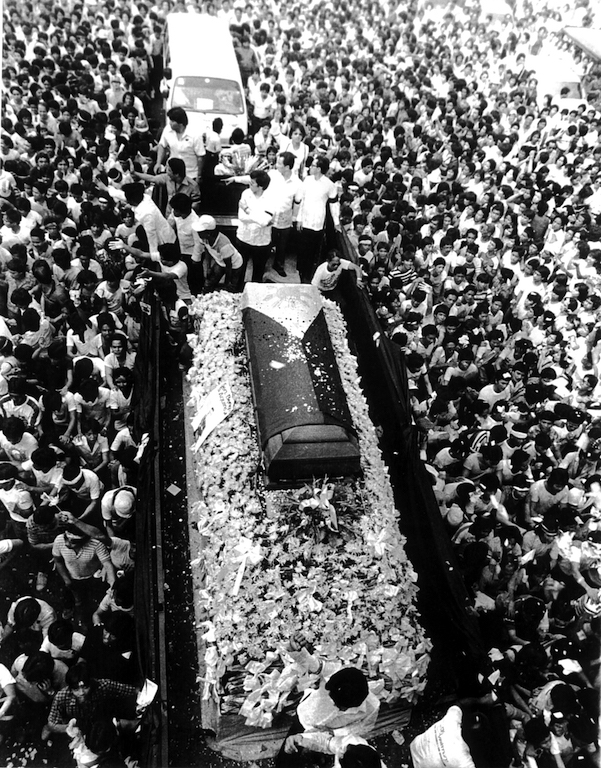

Everyone has been saying that Ninoy was always a “Young Man in a Hurry.” But there was always logic and a sort of rhythm to everything Ninoy did. His mother, in that week of grief in which his body lay in Sto. Domingo Church, visited by seemingly endless lines of mourners, remarked to me that “perhaps Ninoy was always in a hurry, because he knew in his heart that his life will be so short.”

The truth is that Ninoy could have taken a short cut to national leadership (he was already “living” in Malacañang) by remaining within Magsaysay’s circle of power. But that simply wasn’t Ninoy’s way. He perceived that the only way to serve the people was to understand the people.

He went back to his beginnings in Concepcion, Tarlac, and ran for mayor. True to type, he became the youngest mayor in the country’s history (he even had to produce a birth certificate to prove to his critics and adversaries that he was “of age”). At 23, the youngest municipal mayor, he became, at 27, the nation’s youngest vice-governor, and at 29, the youngest governor.

Ninoy, that “Magsaysay boy” (who commuted daily between Tarlac and the Palace), was a fervid Nacionalista and his advice and support was sought by President Carlos P. Garcia. But Diosdado Macapagal of the Liberal Party rode to victory over Garcia.

Macapagal bled Tarlac to the bone. No public works appropriations, no “pork barrels.” Macapagal’s condition for releasing money for Tarlac was no less than abject surrender on the part of Ninoy. His ultimatum: Ninoy should swear himself as a Liberal.

Ninoy went to see me, along with other friends, to explain his capitulation. He said to me: “I took the only course left open to me. I kissed my innocence goodbye.”

Once he had crossed the bridge, Aquino became Macapagal’s close confidant and a pillar of the Liberal Party. But he had crossed the fence at an ill-starred hour. No sooner had he comfortably settled in as an LP than Ferdinand E. Marcos (ironically the former party president of the Liberals) crossed over in the opposite direction. Marcos was nominated presidential standard-bearer of the opposition Nacionalistas in a surprise second-ballot upset at the Manila Hotel, trouncing Macapagal in 1965.

By 1967, Marcos was still riding high. He decided to barnstorm all over the country to promote the Nacionalista local candidates and the senatorial ticket, vowing to crush all LP opposition. He predicted an eight-zero “shut-out” in the senatorial elections that year. Ninoy, knowing from bitter past experience that he could not remain a provincial governor while Malacañang’s purse strings were in hostile hands, decided it was time to go for broke – to run for senator.

Boy Wonder

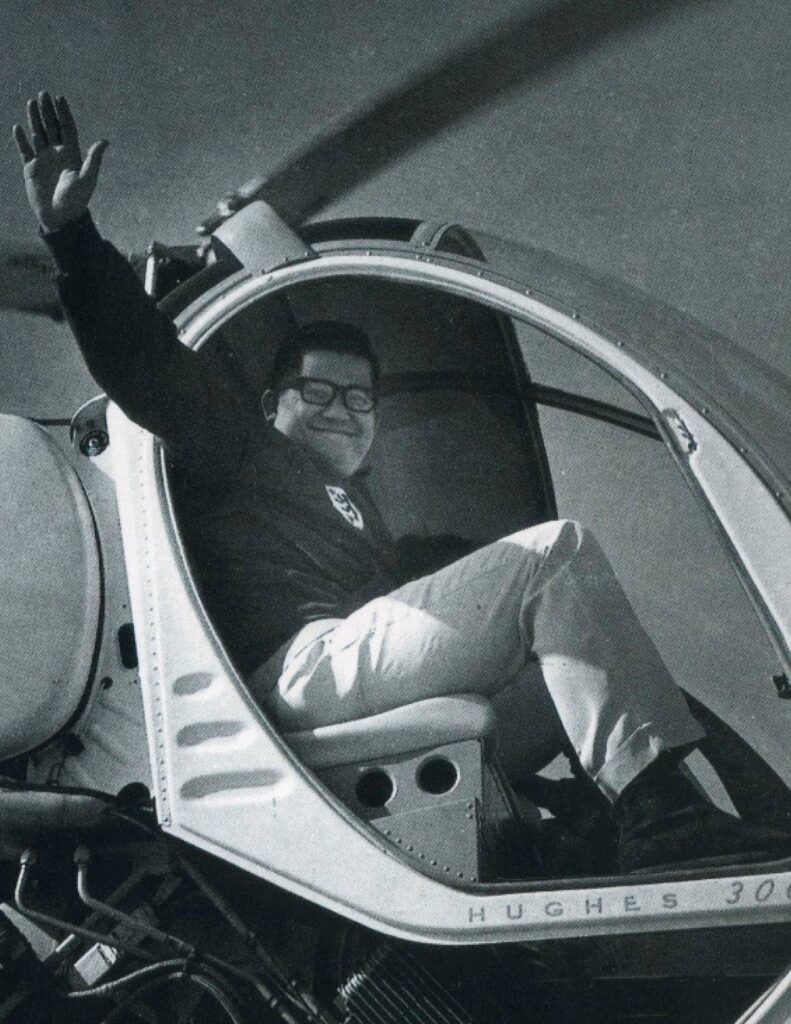

It can be said that Ninoy—the relatively unknown Boy Wonder, the country yokel from Concepcion – made up for the national prominence of his rivals, the older senatorial contenders on both NP and LP line-ups, by waging a campaign of tireless locomotion. Ninoy was obsessed with gadgetry, and he put these to work for him – walkie-talkies, sophisticated radios, computers. He island- hopped by private aircraft and helicopter, giving speeches from barrio to barrio and shaking hands endlessly. His trademark became jumping in and out of helicopters.

“You know, you arrive in a car,” he explained later, “lahat kayo naka-kotse (all of you are riding in cars) – and people don’t look at you. But you arrive from 2,000 feet up and people will gather from all over to watch you come down. Right there you have an audience, an automatic audience. Hover over a town and circle it three or four times before you land and people will come to seeyour chopper, especially from far-off places like Lake Lanao or Northern Luzon.”

What’s more, the Nacionalista Party had led a motion on Oct. 29, just two weeks to go before the polls, seeking to disqualify Aquino for being below legal age! The battle was one of semantics. The 1935 Constitution, as amended, states that a senator must be at least 35 years old “at the time of his election.” On Nov. 14, 1967, Election Day, the Nacionalistas pointed out Ninoy would still be just 34 years old, 13 days shy of reaching 35. Ninoy would turn 35 on Nov. 27. Ninoy and his lawyers replied that the Constitution also declared that 30 days after “the election, the winners shall be proclaimed.”

The Aquino legal argument hinged on the specific wording of the Constitution, which stipulated: “at the time of his election” not “at the time of the elections.” On Nov. 6, the Comelec chucked out the NP suit for lack of jurisdiction, which threw the case on the lap of the Supreme Court. The supreme tribunal, in turn, postponed the deadline for Ninoy to submit his answer to Nov. 18, or four days after election day. This meant that Ninoy could stay in the race. When all the ballots had been counted, Aquino was the only “survivor” in a Liberal Party rout – and what a showing he had made! He was nosed out as a “topnotcher” only by the veteran Sen. Jose J. Roy (Nacionalista), by coincidence a fellow Tarlaqueño, who got 3,770,000 votes against Ninoy’s 3,650,000.

In the Senate, Aquino’s investigative and historic talents came to full flower. Ninoy’s gift was that he was a phrase-maker. He hammered on the theme that the 1967 elections had been characterized by “Guns, Goons and Gold.”

“We must criticize to be free,” he asserted in one speech, “because we are free only if we criticize.”

And he also constantly put his double- barreled mouth to good use in living up to that injunction of his. In 1968, his rst year in the Upper House, he warned that Marcos was building up “a Garrison state” by “ballooning the armed forces budget,” saddling the defense establishment “with overstaying generals” and “militarizing our civilian government of ces” — all these caveats uttered almost four years before martial law. He assailed the shenanigans, syndicates, stinks of “the Sweepstakes.” He attacked the San Juanico “Bridge of Love” project (at a time when it was estimated it would cost P66 million) as “Mr. Marcos’ Folly” — “a luxury bridge to nowhere” — when the money could be better used for a special educational fund; to operate rural health units; for Land Reform or an agricultural development fund; or to expand the railroad to the Cagayan Valley or the far reaches of the Bicol regions.

He exposed what he called an Army and Philippine Constabulary “campaign of terror” in Central Luzon, identifying military Death Squads as groups which styled themselves as the “Monkees” to counteract the terror units called the “Beatles.” (The latter were the forerunners, I suppose, of the present New People’s Army “Sparrow” liquidation squad.)

Marcos’ nemesis

In a million different ways, the indefatigable Aquino bedeviled the Marcos regime, chipping away like a beaver at its monolithic façade. His most celebrated speech, insolently entitled “A Pantheon for Imelda,” was delivered on Feb. 10, 1969, and assailed the First Lady’s first extravagant project, the P50-million Cultural Center, which he dubbed “a monument to shame.” In a land where so many people were starving, Aquino challenged, why should an ostentatious edifice be built “so the bejeweled elite, the nation’s first 100 families… can live it up!” He called Imelda “The Fabulous One” and declared:

“I have risen at the risk of Mrs. Marcos’ scorn and wrath, because a voice must be raised to try and put a stop to the First Family’s wasteful misuse of public money.

“I have risen at the risk of her fury, because country and people demand they cease those wild Palace and yacht bacchanalian feasts.

“I have risen at the risk of her spite, because out there, barely 200 meters away from a fabulous Imelda Cultural Center, a ghetto sprawls, where thousands of Filipinos are kept captives by misery and poverty… I have risen at the risk of her spite, because I am plainly revolted by this will to immortality while the nation suffers and lies on the razor’s edge.”

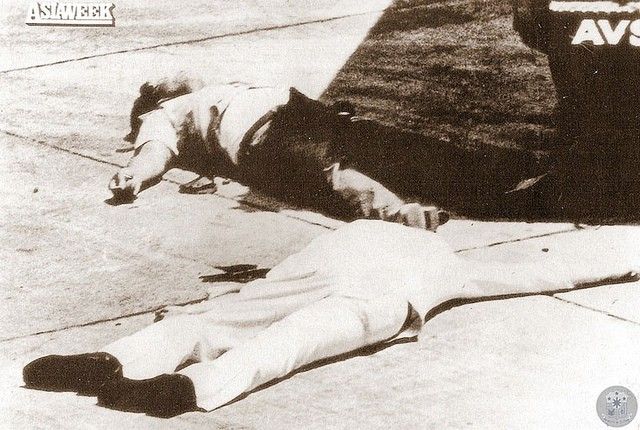

It was not until the Plaza Miranda bombing however – on Aug. 21, 1971 (12 years to the day before Aquino’s own assassination) – that the pattern of direct confrontation, the grand collision between Marcos and Aquino emerged.

At 9:15 p.m. on that day at the kick-off rally of the Liberal Party, the LP candidates had formed a line on the makeshift platform and raised their hands as the crowd applauded them. The band played, a fireworks “show” drew all eyes – but then there were two loud explosions that were not part of the fireworks. The stage became a scene of weird carnage.

It was later discovered by the police that two fragmentation grenades had been thrown at the stage by “persons unknown.” Ramon Bagatsing, later to win as Manila Mayor, lost his leg from just below the knee. Jovito Salonga lost the sight of his left eye, hearing in his left ear and his arms and fingers were mangled. John “Sonny” Osmeña’s kneecaps were smashed. Gerry Roxas, Eva Estrada Kalaw, Ramon Mitra, Melanio Singson, Salipada Pendatun, Eddie Ilarde and Salvador Mariño were hurt and hospitalized for weeks, but recovered.

Although the nger of suspicion pointed at the Nacionalistas, the Marcos henchmen sought to deflect this by insinuating that, perhaps, Aquino might have had a hand in the blast — in a bid to eliminate his potential rivals in the party. Ninoy, indeed, had not been on the damned entablado — he had been delayed at a wedding party at the Jai Alai building on Taft Avenue (he was the Ninong) of one of Sen. Salvador Laurel’s children. Moreover, as his fellow Liberals pointed out later, Ninoy was invariably the “last speaker” at LP rallies. He was the most sought-after bomba speaker at each affair and was therefore scheduled close to midnight, because after his speeches the crowd tended to melt away.

Marcos suspended the Writ of Habeas Corpus, vowed that the killers would be apprehended within 48 hours (they never were), and arrested a score of alleged “Maoists” on general principles.

The Liberals crushed the Nacionalistas in the senatorial contest, with six LPs topping the list, led by Jovito Salonga (4,321,000 votes), Genaro Magsaysay (3,656,000), John Osmeña (3,576,000), Eddie Ilarde (3,571,000), Eva Kalaw (3,482,000) and Ramon Mitra Jr. (3,051,000). Only Ernesto Maceda and Alejandro Almendras (both more than 300,000 votes behind Mitra) survived the catastrophe.

Martial Law

But the almost “private” battle between Marcos and Ninoy found its culmination with the declaration of Martial law on Friday, Sept. 22 (not 21 as all the government bulletins bill it) in 1972.

Aquino and many others sensed that something was afoot. On Sept. 18 at 7:30 p.m., Aquino had appeared (at his request) on my television talk show on Channel 4 and used the program as a forum to expose “Oplan Sagittarius.” (His mistake was to believe, subsequently, that once it was exposed, the plan might be scotched.)

Aquino was picked up at midnight while attending a House Senate committee meeting in the Manila Hilton. An officer whom he knew well, Col. Romeo Gatan (a former PC provincial commander in Tarlac) telephoned him from the lobby and then went up to his seventh floor room to serve the warrant of arrest. Gatan (subsequently promoted to general) advised Ninoy to tell his bodyguards not to resist since the Metrocom had surrounded the hotel with 200 men. Then he bundled the senator into his car and brought him to Camp Crame in Quezon City.

I was arrested two hours later at my home in San Juan. By the morning’s first light, there were more than 400 prisoners crammed into the gym at Camp Crame. At about 8 a.m. or thereabouts, a colonel strode into the gymnasium and started rattling out a list of names: Aquino, Sen. Monching Mitra, Sen. Jose W. Diokno, former Sen. Franciso “Soc” Rodrigo, Manila Times publisher Joaquin “Chino” Roces, Free Press publisher and editor Teddy Locsin, Napoleon Rama of the Free Press who was also a Constitutional Convention delegate, Constitutional Convention delegates Voltaire Garcia and Jose Mari Velez (who was also a Channel 5 newscaster), labor leader Vicente Rafael and myself.

“Will the following gentlemen please step forward,” the officer said.

We began to suspect the worst. Why, of all the 400 or more assembled in that gym, had the 11 of us been singled out? Ninoy didn’t help matters. He stood beside me and cheerfully nudged me in the ribs, whispering: “Eto na, eto na! (Here it is, here it is!) Firing squad na tayo!” We were marched out of the gym and a military bus, khaki painted, with windows sealed with chicken wire, was awaiting us — plus an impressive escort of about 18 blue Metrocom cars, their lights flashing. Our motorcade, however, went only about 200 or 300 yards. We were instructed to alight again and herded into a small one- story barracks building. Ninoy couldn’t have been more cheerful.

“Aba!” he said. “We are going to be shot here in Crame after all.”

Grace under pressure

“Soc” Rodrigo, whom we were to call our Bishop or our “Monsignor,” took out his rosary and asked all of us, his captive congregation, to join him in prayer. Ninoy discovered that there was a shower stall at the rear of the room and decided to take a shower. “What do you want to do that for,” I grumbled, “if they’re only going to shoot us anyway?” And Ninoy cracked, at that point, what I thought at the time was the most tasteless quip of his career: “At least I’ll meet my Maker clean!” I took a shower, also.

That was Ninoy. Brave, even cheerful in the face of danger. We came to realize that his antics were designed to put us, his fellow prisoners, at ease. He wasn’t grandstanding. He was trying to cheer everybody else up. It has been said that courage can only be defined as “grace under pressure.” Aquino, in that dark hour, exhibited that grace. He was thinking, not about himself, but about others.

After a wait of hours, they came for us again, loaded us back into that bus – and off we went merrily down EDSA, the Metrocom cars with their sirens wailing and their lights flashing.

We speculated whether the convoy would turn right at Buendia Avenue – so we could be shot at the Luneta like Jose Rizal. But we turned left and sped directly into Fort Bonifacio’s MSU (Military Security Unit) compound. They didn’t line us up for the firing squad that day.

The next morning, Sunday, the military sent us a priest to say Mass for us and hear our confessions. Ninoy laughed. “Oh boy, at least we’ll have a chance to go to confession before… you know.”

Voltaire Garcia was my first cellmate, but we soon found out that he was ill. (Poor Voltaire succumbed to leukemia a few months later.)

My next cellmate was Ninoy. And I confess that when I was assigned to be Aquino’s cellmate, I wasn’t flattered. My heart sank to my knees. By that time, we had all come to the conclusion that the main target of this entire exercise of martial law was Ninoy Aquino and we were just the “supporting cast.” I reasoned that since I was Ninoy’s cellmate, I would be there forever.

But I wasn’t bored because I had Ninoy to entertain me. We talked and talked, and read and read. We traded ideas. We argued ideologies. We cracked jokes. We read until they were thumb-worn back issues of Playboy magazine, which my wife had sent in to me. (Don’t ask me why, ask Freud.) We read books. (By the time Ninoy was allowed to leave his lonely cubicle, years later, he must have read 5,000 books!) We dreamed dreams.

It was then I realized that Ninoy Aquino, for all his wit, his air of right cynicism, and his veneer of tough political pragmatism, was an incurable romantic.

One day, out of the blue, he said to me: “Don’t worry, Max. Within six months to one year, we’ll both be out of here!

“The Filipino people are used to democracy – they love liberty. You just can’t take it away from them. I have faith in our people. Within six months to one year, the Filipinos will stand up and demand our freedom!”

I shook my head sadly, “Ninoy,” I said, “we had better dig in for the long haul. Marcos is the greatest group dynamics expert in this neck of the woods, and he’s studied the Filipino’s weaknesses. Tinimbang tayo ngunit kulang.” (We were weighed and found wanting.)

I was wrong on only one signi cant point. I wasn’t there for five to 10 years. To our surprise, all of us except for Ninoy and Pepe Diokno, were released within less than three months. (Diokno remained another two years in the same compound, while Ninoy suffered seven years and seven months in solitary confinement.)

Unbowed and unbroken

Ninoy’s optimism was a revelation. For the treatment at the hands of his captors had grown worse after most of us had gone, not better. By March 1973, as Ninoy himself recounted it in a letter to “Monsignor” Soc Rodrigo, he was averaging 1,200 Hail Mary’s a day.

On March 12, Ninoy was led to a blue Volkswagen Combi and saw Pepe Diokno already seated inside. The two of them were hustled aboard a blue and white helicopter “with a presidential seal,” blindfolded and handcuffed. The chopper took off and landed (as they found out weeks later) in Fort Magsaysay in Laur, Nueva Ecija. “When the blindfold was finally removed,” Ninoy recalled, “I found myself inside a newly painted room, roughly four by five meters with barred windows, the outside of which was boarded with plywood panels.” Only a six-inch gap between the panels provided air and light. A bright neon tube burned day and night. There were no electric switches, the room was bare except for a steel bed without mattress. No chairs, tables, nothing.

Ninoy was stripped naked, his wedding ring, watch, eyeglasses, shoes, clothes, taken away. A guard brought in a bedpan and said that he would be allowed to go to the bathroom only once daily in the morning to shower, brush his teeth and wash his clothes. He was issued two jockey briefs and two T-shirts and instructed to wash one set everyday. Diokno apparently occupied the adjoining “box,” but they were warned not to try to communicate with each other.

The cruel part of this punishment (Ninoy was never informed what they were being punished for) was that all his belongings – ring, watch, glasses, were given to his wife, Cory, without explanation. For a horrified period of time, his mother and his brothers and Cory and the children, sisters, could only despair that Ninoy was dead. Eventually they located him, but they were powerless to do anything. Ninoy and Pepe endured 30 days in their stifling boxes – during the hottest time of the year. It was a transparent attempt to break Aquino’s and Diokno’s will.

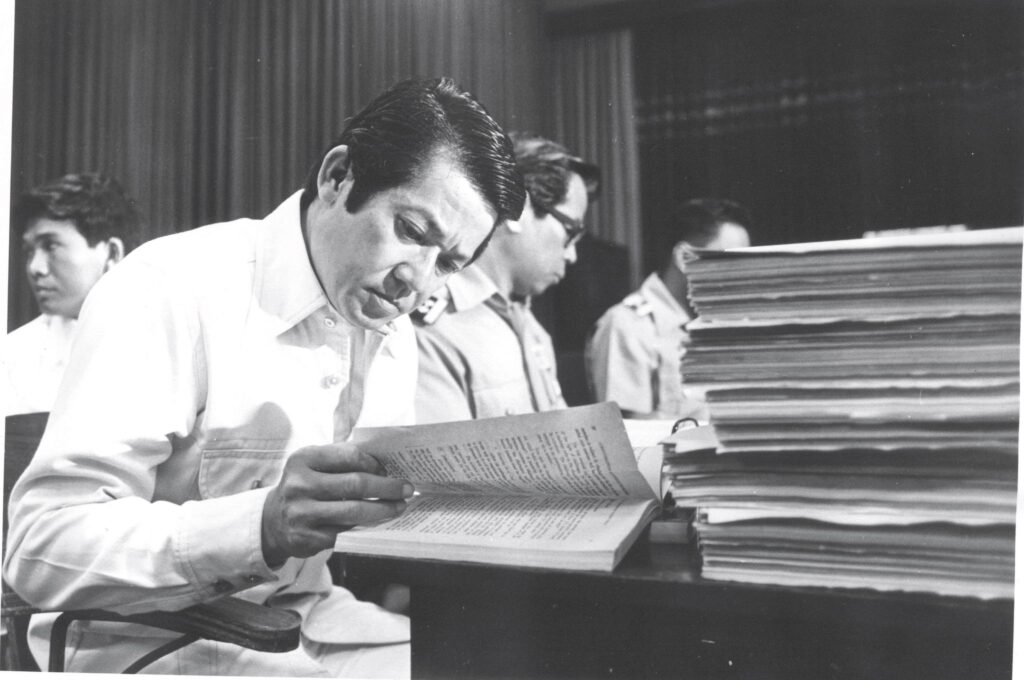

On Aug. 27, 1973, back in Bonifacio, Ninoy was brought before the Military Tribunal, specifically Military Commision No. 2 chaired by Brig. Gen. Jose G. Syjuco. Ninoy was charged with alleged violations of Republic Act No. 1700, the Anti-Subversion Law, with four separate charges and a total of nine specifications including murder, subversion, illegal possession of firearms. He refused to take part in such a farce of a trial, asserting that military of cers should not be allowed to try him since their Commander-in-Chief, President Marcos, had already declared him “guilty” in his public pronouncements.

Moreover, sentence by a military tribunal did not permit him an appeal to the Supreme Court. “I will not participate,” he stated. “You can dispose of my esh, but I cannot yield to you my spirit and conscience.”

Aquino’s defiance led to the suspensions of hearing for a year and a half. On March 31, 1975, his objections were brushed aside by the tribunal which proceeded to “reinvestigate” witnesses against him, Huk Commanders Melody, Ligaya and Pusa, Tarlac politician Max Llorente, and others. Ninoy put up no defense for the trial that was launched in 1973 and finally concluded in 1977. He simply expressed his innocence.

On April 4, 1975, he announced that he was starting a fast to the death to protest the injustice of his military tribunal. Ten days after the “fast” began, he instructed his lawyer to withdraw all motions he had submitted to the Supreme Court. As weeks went by, he took no food, only salt tablets, sodium bicarbonate, and amino acids and two glasses of water a day.

Even as he grew weaker, undergoing chills and cramps, the soldiers forcibly dragged him to the military tribunal’s session. His family and hundreds of friends heard Mass nightly at the Santuario de San Jose in Greenhills, praying that he would not die. Near the end, Aquino’s weight had dropped from 160 to only 120 pounds, and he could neither stand nor sit. On March 13, 1975, on the 40th day of his fast, he noted that it was the Feast of Our Lady of Fatima. His family and several priests and friends, begged him to stop his fast, pointing out that even our Lord had only fasted 40 days and nights. “I want to die today,” he prayed to God, “but if You do not allow me to die, I’ll take it You want me to continue my work. Your will be done.”

He survived. He had made his gesture. Offered his sacrifice up to God. But at 10:25 a.m. on Nov. 27, 1977, Military Commission No. 2 sentenced Aquino and his two co-accused, Bernabe Buscayno (Commander Dante) and Lt. Victor Corpuz, to death by firing squad.

Ninoy called the act an “indecent and immoral rush to judgment.” But as he said, “a time comes in a man’s life when he must take a stand and make a painful decision: to willingly die for his principles or surrender. I have opted to die for my principles because my cause transcends my individual self and freedom.”

‘LABAN’

However, the official firing squad was denied Ninoy Aquino. In 1978, from his prison cell, he was even allowed to “take part” in the elections for an Interim Batasang Pambansa (Parliament). Thus his political party, dubbed “Lakas ng Bayan” (People’s Power) was born, with a fighting acronym that was more than appropriate: “LABAN.” Ninoy was allowed one “television” interview from his cell on Face the Nation and proved to a startled and impressed populace that imprisonment had neither dulled his rapier-like tongue nor dampened his fighting spirit.

Foreign correspondents and diplomats asked us what would happen to the LABAN ticket. All agreed that LABAN would win on Friday election day, but lose the next day. On Thursday night, at 9 p.m., a massive noise rally transformed Metro Manila into a festival of jubilant and defiant protest. The “noise rally” was supposed to last for only 15 minutes, but everybody seemed to be out in the streets, cars and jeepneys horns honking, banging at pots and pans, blowing whistles and shooting off firecrackers.

Malacañang was shaken by what had transpired, former Press Secretary Francisco “Kit” Tatad revealed (after he had quit the Cabinet). But, looking back, the very success of the almost spontaneous noise rally (nobody, even in LABAN’s top councils, could pinpoint who had first spread the word about it) was the Opposition’s undoing. The metropolis-wide phenomenon had alerted the President and his KBL that the Opposition was strong enough to topple their 21-member slate (led by Imelda) in Metro Manila.

Following the emotional upsurge of the LABAN campaign and the letdown of “defeat” on April 7, 1978, Ninoy’s life in his Fort Bonifacio cell reverted to drudgery. Word ltered in to Ninoy that American President Jimmy Carter, in his international campaign for human rights, had warned Mr. Marcos that if anything happened to Aquino, there would be an immediate “chill” in relations between Washington D.C. and Manila. Was this rumor or fact? Nobody would admit to it. But Ninoy continued to stand pat on the challenge he had hurled at the Military Commission: “If Marcos thinks I am guilty, let him shoot me tomorrow.”

Matters of the heart

In early 1980, about mid-March, he suffered his rst heart attack. Being locked up in a cage, in solitary con nement at that (a cruel punishment for an extroverted and naturally gregarious individual), the unremitting test of wills between him and Marcos and the Military Tribunal which had nally condemned him, the rigors of his 40- day fast, had at last exacted their toll on his body. The camp doctor examined him and advised him merely to rest.

At length, the doctor agreed to ask permission to take Aquino to the Heart Center in Quezon City for tests. A couple of days later, Aquino received a letter on of cial stationery. When he read the letter itself, his mouth (he recounted later) dropped open. The letter had been written to “regretfully” inform him that the camp doctor had died of a “massive coronary” the afternoon before.

“Oh, wow,” Ninoy remarked. “Here he was reassuring me that there was nothing wrong with my heart – and the poor fellow couldn’t even diagnose his own heart condition!”

At the Heart Center, Ninoy suffered another attack and the doctors were able to take his ECG right there and then. They found out that he had blocked arteries. The director of the Heart Center did not want to operate on Ninoy because he did not want to be involved in such a controversial matter. Besides, Ninoy refused to submit himself to any surgery at the Heart Center, preferring to return to Fort Bonifacio.

Ninoy asked Deputy Minister of Defense Carmelo Barbero to inform President Marcos of his heart ailments and also Ninoy’s request to go to the Baylor Medical Center in Dallas, Texas. Barbero instructed Ninoy to write to Marcos and Ninoy did.

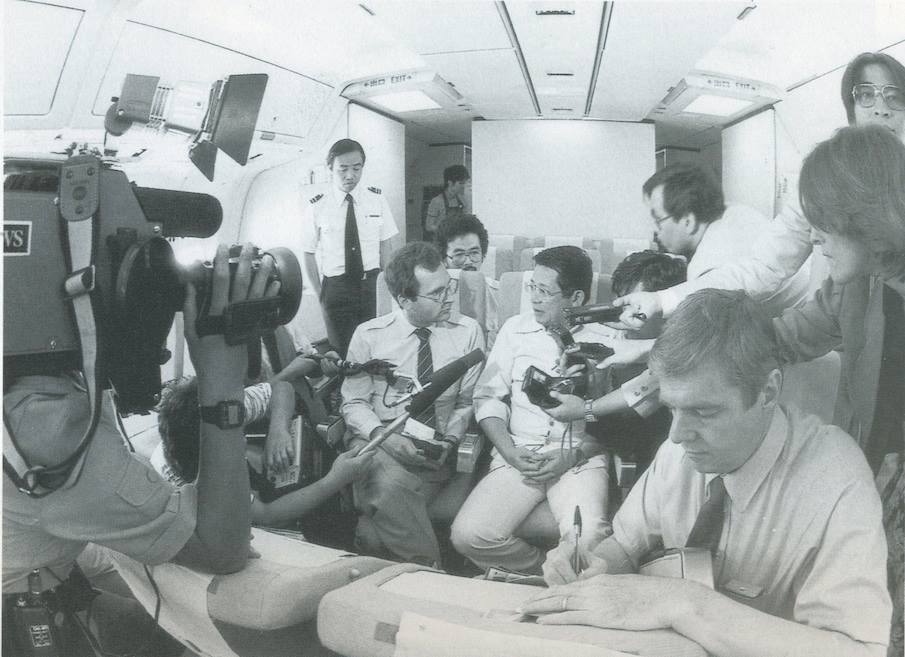

On May 8, 1980, Imelda Marcos came to Ninoy’s hospital room. She asked him if he would like to leave that evening for the U.S. She then ordered General Ver and Mel Mathay to make the necessary arrangements for passports, visas and plane tickets for the Aquino family.

Ninoy, in his weakened condition, had to rest brie y in California before enplaning anew for Dallas, Texas. When he got there, his friend, the renowned cardiologist, Dr. Rolando Solis (of Romblon) con rmed the Heart Center’s original diagnosis. He asked Ninoy when he wanted to go under the knife. “If you’re superstitious, tomorrow’s Friday the 13th.” Ninoy glanced at the calendar and recalled that Friday was the Feast of Our Lady of Fatima, the same day eight years previously that he had ended his 40-day fast. “Hit me tomorrow!” Ninoy told Solis. He said that if God permitted him to survive the second time, it would be an indication that God still had work for him to do.

Ninoy was operated on in Dallas, Texas and not only recuperated speedily, but was jogging within two weeks and making plans to y to Damascus (Syria) to contact Muslim leaders just ve weeks after. When he reiterated that he was returning to the Philippines, he received a message from the Palace saying that it would be all right for him to extend his medical furlough. Eventually, Aquino decided to renounce his two covenants with Malacañang “because of the dictates of higher national interest.”

Exile

Aquino spent three happy years in US “exile,” setting up house with Cory and the kids in Newton, a suburb of Boston, Massachusetts. On fellowship grants from Harvard University and Massachusetts Institute of Technology, he worked on the manuscripts of two books and gave a series of lectures to packed halls, classrooms and auditoriums. He rocketed all over the US delivering speeches critical of the Marcos government. The President and his of cials, in turn, accused Ninoy of being the “Mad Bomber” behind a rash of bombings, which had erupted in Metro Manila in 1981 and 1982.

Aquino denied that he was advocating bloody revolution but warned that new oppositionists were threatening to use violence soon. He urged Marcos to “heed the voice of conscience and moderation,” and declared that he was willing to lay his own life on the line.

In one memorable speech, Aquino averred:

“I have asked myself many times: Is the Filipino worth suffering or even dying for? Is he not a coward who would yield to any colonizer, be he foreign or homegrown? Is a Filipino more comfortable under an authoritarian leader because he does not want to be burdened with the freedom of choice? Is he unprepared, or worse, ill-suited for presidential or parliamentary democracy? I have carefully weighed the virtues and faults of the Filipino and I have come to the conclusion that he is worth dying for.”

Although many Filipino audiences in America responded to his spell-binding perorations and were attracted by both his militant message and his charisma, Aquino was saddened to nd the great majority of “stateside Pinoys,” apathetic. They were too busy building up careers in a new land, striving to nd a place under the California sun or a toehold in the Eastern seaboard. He was surrounded by many American admirers, but he longed for home. When we would talk to each other on the telephone, he kept on repeating: “I’m coming home! I must come home!”

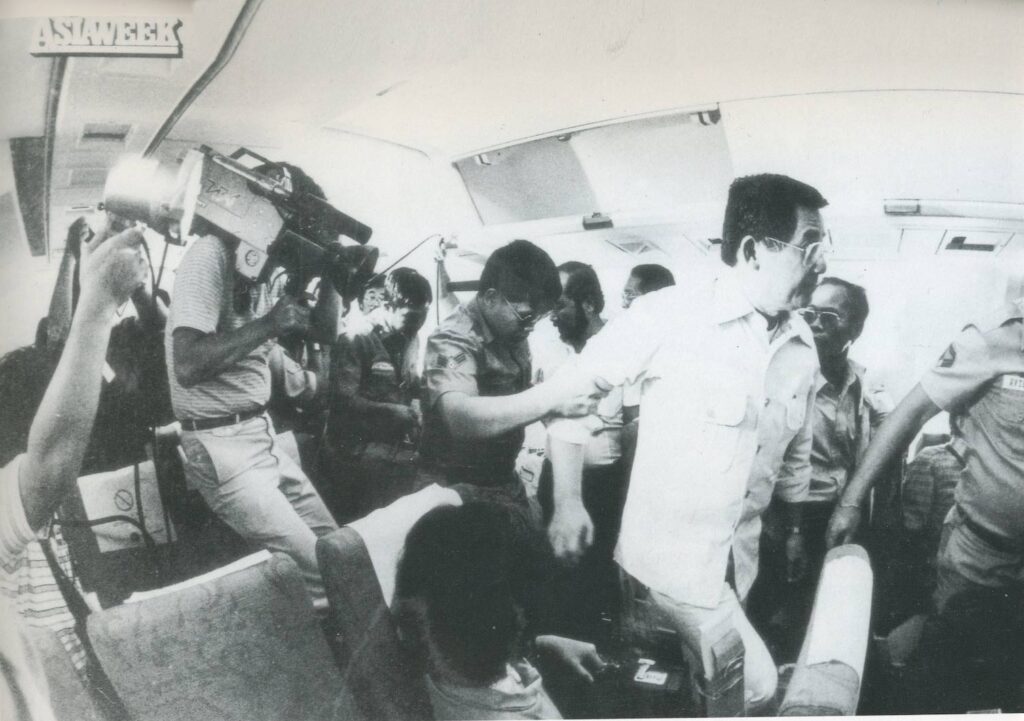

Finally, in 1983, Ninoy made his decision to return to the Philippines. The rst target date was Aug. 7, which he later pushed back to Aug. 21. His mother, his wife, his family urged him to reconsider his decision. Imelda herself warned him (when they met in New York) that if he insisted on coming home, he’d be dead.

When his sister Lupita Kashiwahara arrived in Manila from San Francisco as his “advance team,” she brought with her Ninoy’s nal answer to all his friends who were begging him not to risk coming home. “If I die, so be it. But I hope my death will awaken our people to the need to stand up and fight for themselves.”

When Ninoy invoked that favorite and fatalistic expression, “So be it,” it was a signal that his mind was made up. Stubborn, gallant, romantic Ninoy.

The rest is history.

Editor’s Note: This piece was written by the late Max Soliven in homage to Ninoy on the latter’s 20th death anniversary in 2003. The same piece came on August 2013 in PeopleAsia’s special issue commemorating Ninoy’s 30th death anniversary.