Now that we’re in the grip of the COVID-19 pandemic, people the world over have found unlikely heroes in their healthcare workers. What’s it like these days to be a doctor or nurse living and battling it out in the frontline? PeopleAsia interviews two of them.

By Alex Y. Vergara

“One of the most difficult demands of being a doctor these days is seeing the patient die.” So, declares Dr. Juan Carlos “JC” de Leon (not his real name), one of the many frontline healthcare workers in the country who has responded to the call of the times.

He continues: “What makes it more difficult, as one of my mentors said, is that this time, there are no embraces between people, just dejected looks. No relatives are there to comfort the patient. No words. The hardest part is there are no wakes, no time to send off the deceased, no more goodbyes for those left behind.”

Now that we’re in the grip of the COVID-19 pandemic, people the world over have found unlikely heroes not in their policemen and soldiers, but in their healthcare workers—doctors, nurses and even orderlies who stay up long hours in hospitals risking life and limb attending to patients infected with the deadly novel coronavirus from which there’s still no known cure or vaccine.

Cheers and applause

From Italy to India, France to Turkey, grateful citizens, a good number of whom have friends and loved ones who are either sick of or have succumbed to COVID-19, step out of their houses or go to their balconies at exactly 8 p.m. every evening since the crisis deepened and became more apparent a little over a month ago, to cheer on and applaud their respective healthcare professionals.

It’s the least they could do, really, to honor and buoy the spirits of people who man the frontline in a borderless and unconventional war with an unseen enemy, which has so far also proven cunning and ruthless. And like all conflicts, there have been casualties—nearly 20,000 deaths so far, including many of the finest doctors and nurses from the world over who once walked this earth and helped heal people.

For sure, this isn’t the first nor will it be the last pandemic the world would be witnessed to. But the COVID-19 crisis is the first and biggest modern-day contagion of its kind since the Spanish flu pandemic in 1918, which no one alive today, except for a handful of supercentenarians, has lived through or personally remembers. Three months on since the first cases of COVID-19 appeared in Wuhan, China, the war rages with no immediate end in sight.

After the calm before the storm, an uneasy two months when not a few Filipinos spent going about their business while wishing that the country be spared of the virus—an exercise in wishful thinking in a globalized world where air travel has become routine, tourism and the deployment of overseas Filipino workers to parts unknown vital lifelines to the country’s economy—COVID-19 has finally made its presence felt, and how, just soon after March rolled in.

Steadily rising

As of this writing, the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases in the Philippines has steadily climbed to 636, including 38 deaths. The number, of course, is expected to increase in the coming weeks. By how many would greatly depend on the success or failure of the government-imposed Luzon-wide enhanced community quarantine.

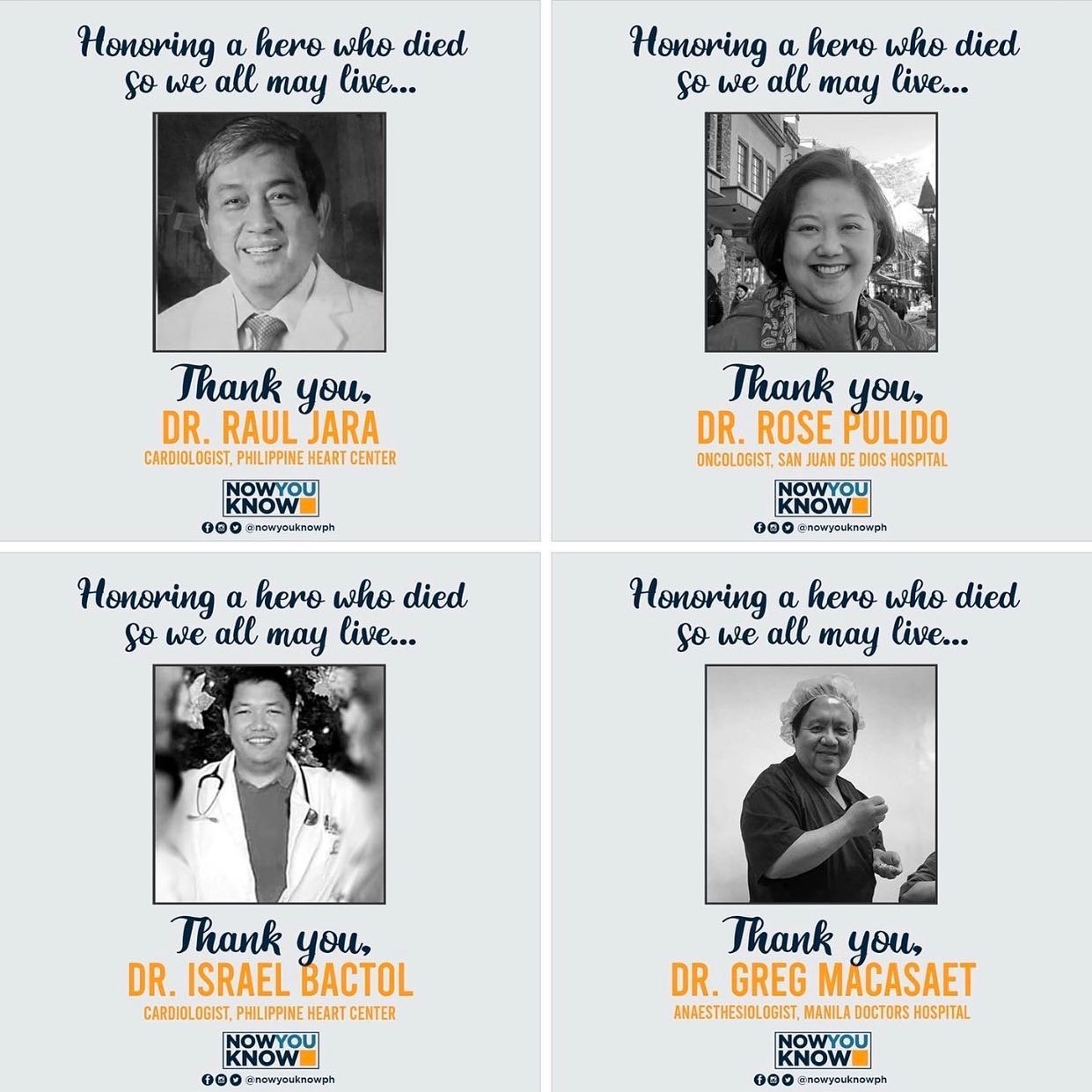

This early, several Filipino doctors, including two leading cardiologists, an anesthesiologist and an oncologist, have died of COVID-19-related complications while staying true to their sworn oath to save lives.

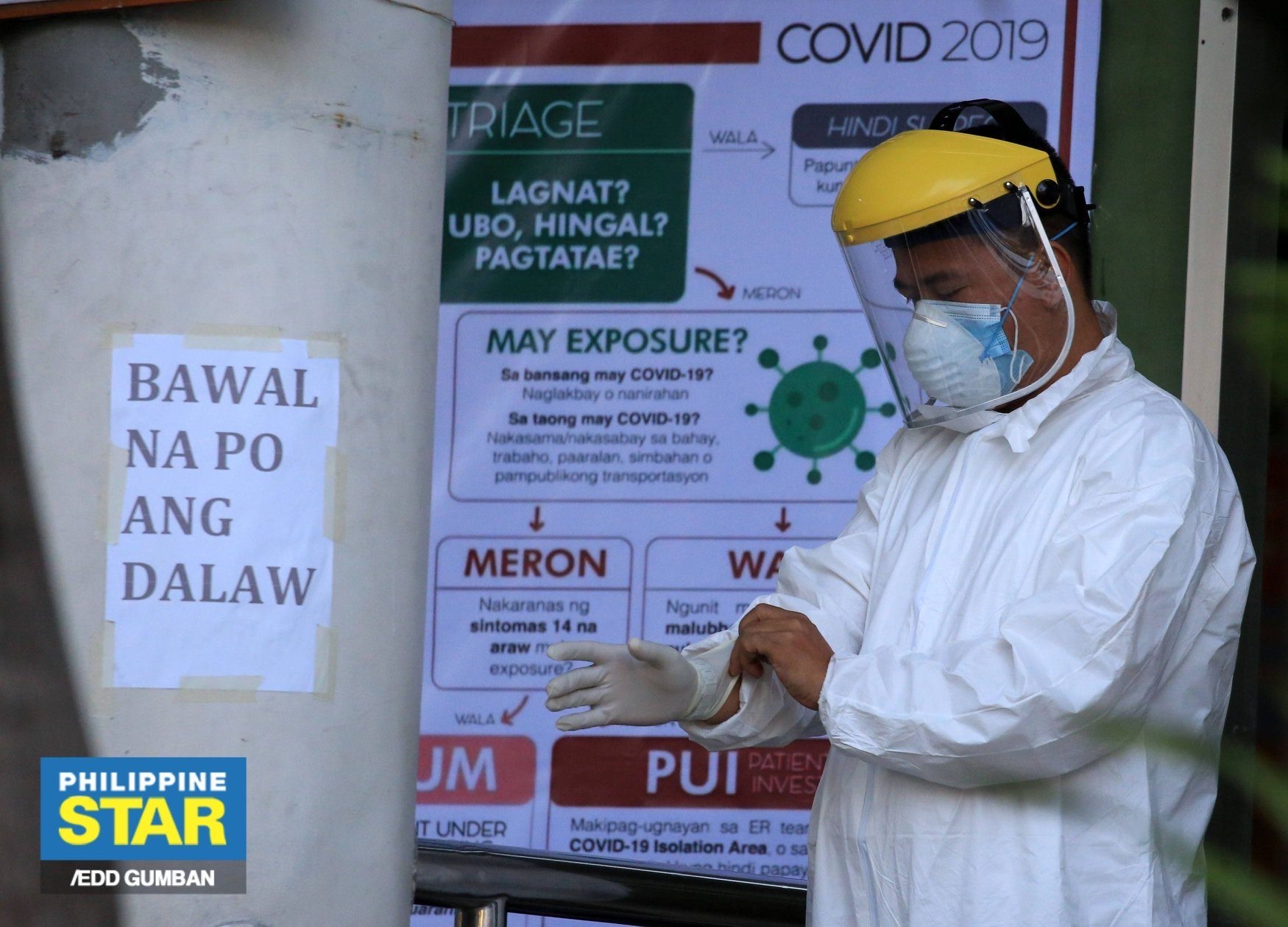

How is it like to be in the frontline these days? To be a so-called front liner armed not with bombs and bullets, but with needles, IV drips, intubating equipment and ventilators? PeopleAsia interviews two of these modern-day heroes, a doctor and a nurse who are both in their late 20s, working for different hospitals in Metro Manila.

In keeping with the World Health Organization’s order to practice social distancing, we conducted this interview via Facebook Personal Messenger and email. JC, a neurology resident, requested that we withhold his real identity and the hospital he works for, while ICU nurse Angela Katrina Fonte reiterates that her views are her own and don’t reflect in any way those of The Medical City (TMC).

JC, who began his training as a future neurologist barely three months ago, was called upon by his superiors to tend to the first cases of PUI (persons under investigation) and PUM (persons under monitoring) who began arriving and seeking the hospital’s help earlier this month.

PUI and PUM

A person with cough and/or fever and has a travel history within the last 14 days, especially to countries with issued travel restrictions and significant number of COVID-19 cases, is considered a PUI. He or she warrants hospital admission.

A PUM exhibits no signs or symptoms, but also has a travel history within the last 14 days to countries with issued travel restrictions and significant number of COVID-19 cases. His or her condition warrants self-quarantine and monitoring.

In both cases, a PUI and PUM have also been likely exposed to another person who tested positive for COVID-19. During the early stages of the epidemic, two of the best ways to control its spread were contact tracing and testing of people who were likely exposed to and showing signs of the disease.

Now that widespread infections have gone down to the community level, healthcare authorities have since appealed to people, even to those who are asymptomatic, to treat themselves as if they are also carriers by strictly practicing social distancing and staying at home.

Seasoned critical care nurse

Angela, for her part, has been working for TMC for more than two years now. She has spent the last eight months assigned at the hospital’s ICU. She also served as a critical care nurse for three years in two other hospitals.

“Nowadays, we’re really required to wear personal protective equipment (PPE) in [dealing] with each one of them,” says JC. “So, at any given time, we have double-layer protection.”

To minimize contamination, JC and his colleagues change in and out of the second layer of PPE every time they deal with a different patient. Common symptoms of patients afflicted with COVID-19 include high fever, dry, persistent cough and difficulty in breathing.

“Once the patient presents symptoms similar to COVID-19, we follow an algorithm of classifying them as either PUI or PUM. Once classified, they’re already put in isolation for their safety and that of their relatives, visitors and the rest of the medical team,” says Angela.

Based on released data, TMC has 18 confirmed COVID-19 cases, says Angela. JC is unable to give a concrete number since, apart from a lag in test results, their hospital’s threshold for considering PUIs and PUMs has changed significantly “resulting in the dramatic increase of cases.” Such a development, he says, led to the quarantining of a huge portion of the hospital’s staff.

Palpable sense of fear

While JC admits that a “palpable sense of fear and uncertainty” among overworked hospital staff is evident these days in their workplace, the passion and willfulness to serve the sick remain.

As ICU nurses, Angela and her colleagues are, in her words, “somewhat” familiar in dealing with COVID-19 cases, a condition which usually leads to acute respiratory distress syndrome—a common complication associated with pneumonia as well as COVID-19. But attending to several cases all at once, something they haven’t encountered until now, can be stressful.

“Since we’re dubbed as the hospital’s critical care unit, it was common for us before to encounter one to two toxic cases a day,” she says. “But this pandemic has been testing our strength and faith as a team. We’re assisting each other cope not only physically, but also emotionally, spiritually and mentally. Dealing with a pandemic first hand, we’ve learned, is still overwhelming even for us.”

The constant feeling of fear JC shares with his peers isn’t centered on his safety, but the health and safety of people around him—loved ones, friends and even his colleagues.

“The main challenge for me is not knowing when things will get back to normal,” he shares. “I’ve started this training so that I could eventually build up my practice and fix my life from thereon. With this, there’s no way of telling when it will end.”

Like most young doctors his age, JC never imagined himself facing a pandemic as huge as this in his lifetime. But he’s fully aware of the fact that life-changing events like this one is what “we doctors and other healthcare workers have signed up for.”

As a resident in training, JC considers the time he spends with patients relatively short. As newbies, he and the other residents are spared from frequent duties to limit their exposure to the virus. But since the situation is still quite fluid, all that may change, especially if the country experiences a dearth in trained doctors.

“We are prepared to cover and go full time if the need arises,” he says. “Proper hygiene and the use of PPE are paramount if we are to survive this.”

Possibility of infection

Despite her positive disposition and calm nature, Angela admits that there’s always a lingering fear she and her fellow nurses share regarding the possibility of contracting the dreaded disease themselves.

Apart from properly donning their PPE and following established hospital protocols, Angela and her colleagues have been preparing themselves “holistically” for months before the first COVID-19 cases came bursting through TMC’s doors.

“Even before this pandemic, I have been taking care of myself by boosting my immune system,” she shares. “I’ve been exercising, taking essential vitamins and consulting regularly with a doctor to make sure I’m in great shape. To top it all, prayers to keep me safe at all times.”

She would need every bit of strength in mind, body and spirit, as Angela is on duty these days from 6 p.m. to 6 a.m. Despite her youth, lack of sleep and working in the graveyard shift could take its toll, she admits.

“There’s also less time to eat these days during duty,” she shares. “Before, I still had at least 15 minutes to munch on a snack. But from time to time, I look for an opportunity to eat and drink water. I’m still mindful of the need to keep healthy.”

Otherwise, she continues, the prevailing mood within the ICU remains relaxed and calm. The place may resemble a battlefield, but Angela and the rest of the TMC team don’t let that get to them. They have to think clearly and focus if they are to succeed in clinically stabilizing every patient’s conditions.

“Honestly, I feel at ease working with a team consisting of competent and reliable nurses, doctors, medical technologists, respiratory therapists, radiation technologists and pharmacists,” she says. “Part of it is the thought that we’re working towards one goal, which is to be the best we can be for our patients.”

Living away from home

Since healthcare professionals like JC and Angela are directly exposed to the novel coronavirus themselves, they’ve had to live elsewhere, away from immediate family members to avoid possibly infecting them.

“One of my fears is to bring this (infection) home so I’m living in a dormitory for the time being,” says JC.

Angela, who stays alone in a family-owned condominium unit to isolate herself from loved ones, has done the same.

“It’s for their safety and protection,” she shares. “While away, I just keep an open communication by updating them of my current situation. Once in a while, I go home to pick up some things. I try not to interact with anyone until I’ve washed my hands and showered to prevent the spread of possible infection.”

Since visitors aren’t allowed in the ICU, it has also fallen on critical care nurses like Angela to update patients’ family members on their conditions through phone. Despite doing so for years, such a task has yet to become easy for her.

If there’s an emergency that requires urgent decision, resident doctors take over to discuss it with patients’ immediate relatives.

“Up to now, it’s still heart-wrenching to see patients die without their relatives by their side. As their healthcare provider, we stand by their side until they breathe their last,” she says.

Public support

Amid a general feeling of doom and gloom these days, both front liners still find plenty of reasons to feel joyful and positive. In JC’s case, he and his team have been, in his words, “flooded” with donations in the form of food, monetary support and vital PPE kits.

“We’ve received a pool of endless messages from friends and family alike,” he says. “We cannot begin to thank everyone for being with us in spirit, supporting us as we go through every battle.”

Angela also can’t help but feel buoyed, as she thanks people “for their generous hands and hearts, donating food and providing transport service to the healthcare team.”

Her appeal to the public hasn’t changed since the start of the crisis: “Just stay home, listen and follow rules and guidelines imposed by the government.”

JC’s “simple but important plea” to those in positions of authority is for them to “set their priorities and ensure public safety, never one’s own self-interest or ego.”

And his plea extends to everyone, as front liners like them need all the assistance they can get. That includes listening to their recommendations and solutions with regards to strictly adhering to rules set involving isolation and quarantine.

Regardless of address, education and station in life, we’re all in this together. The common enemy is the novel coronavirus and its alter ego of sorts, which is COVID-19. Only by helping each other, he declares, can we win this war!