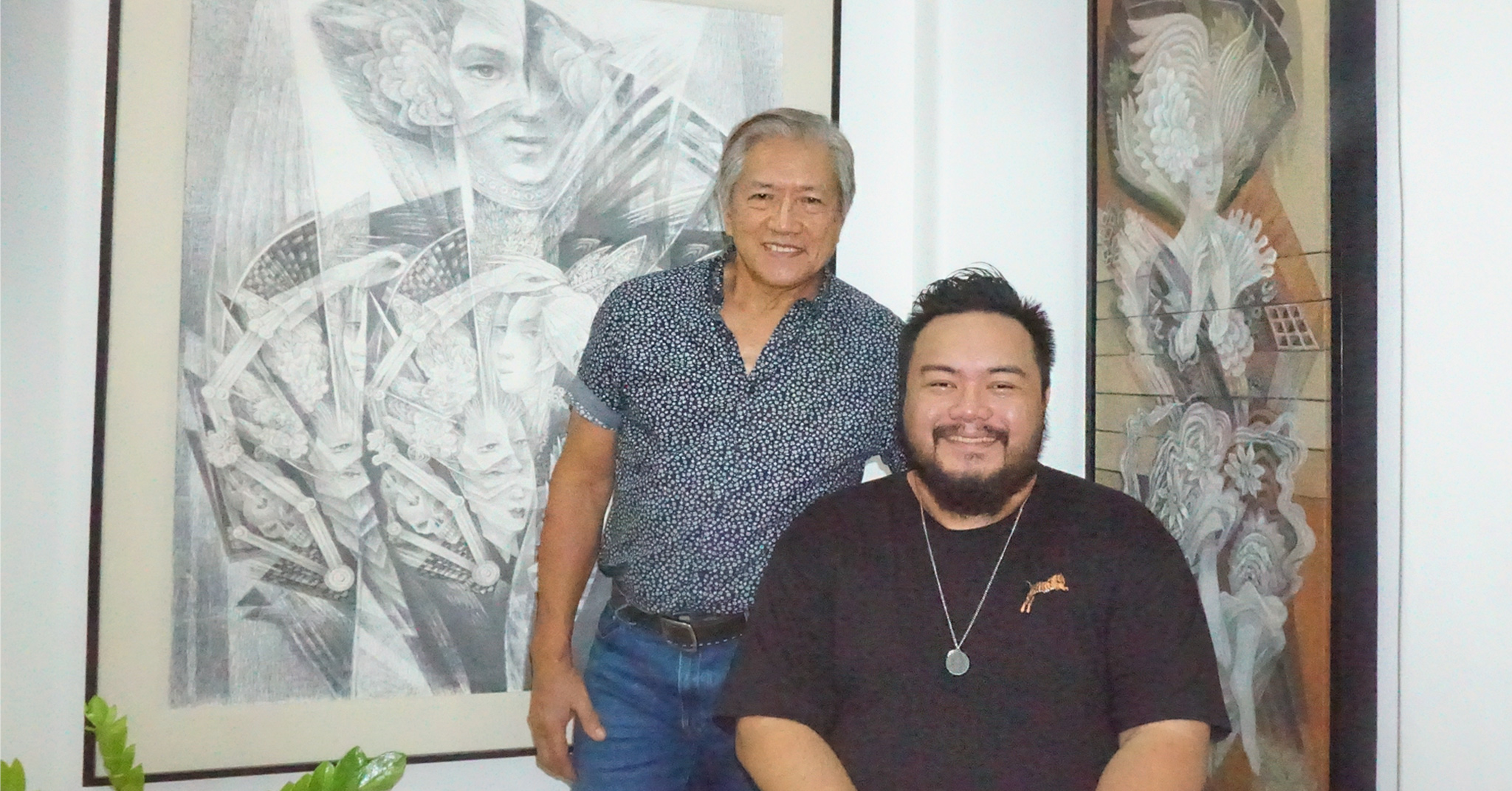

Seasoned artist Fil Delacruz didn’t lead to produce an accomplished artist-son in Janos Delacruz by telling him to do this or to don’t do that. He did it instead by leading through example and the strength of his convictions, which was first put to the test when his then teacher-mother initially wanted him to turn his back on Fine Arts in favor of Education.

By Alex Y. Vergara

Photos by Elizabeth Laus

Although they’re both into surrealism, father-and-son Fil and Janos Delacruz have very different styles, thought processes and sources of inspiration as artists. And because of the gap in their ages, they’re also products of their own time.

And while Fil, 72, has had to struggle during his younger years to convince his parents, especially his strong-willed and practical Bulakeña mother, that a career in the arts offered him a bright, stable future, Janos, 36, encountered no such obstacle. He could have been anything he wanted to be since his father, owing perhaps to his own earlier experience, gave his son the freedom to express himself as he pleased at a very early age.

Since the younger Delacruz didn’t experience any pressure from his old man either to completely shun the arts or, worse, be like him down to the last stroke and color palette, Janos invariably gravitated to becoming an artist himself, even choosing to study and finish Fine Arts at the University of Santo Tomas (UST), the same school where Fil graduated from decades earlier.

Childhood memories

“My first memories as a child, which have remained with me to this day, was my father taking my brother and I to his old studio,” says Janos one rainy afternoon at “Bahay Sining,” the home-slash-studio he shares with his father in Metro Manila. While Fil painted the hours away, his two boys lay on the floor doodling on pieces of paper to their hearts’ content.

“He was never the type of father or teacher who would say do this or don’t do that,” Janos adds. “He simply allowed us to be as we tried to find ourselves.”

As far as Janos remembers, the only time his father stepped in, obviously unable to hide his disapproval, was when he started experimenting by putting together collages of blown-up images taken by different photographers back in college.

“He asked me why on earth was I doing that when I could very well paint images myself,” he says with a chuckle. “It was a period of discovery for me when I was open to doing anything. But, in hindsight, he was right.” In due time, Janos, after having pondered over his dad’s question, picked up paint and brush again and went back to his daily date with the canvas.

Even up to now, he continues, his father’s influence over him and his art has found ways to seep through not because of what Fil says, but how he conducts himself as a person and as an artist. The discipline and curiosity to explore new ideas as well as to venture out of his comfort zone to adapt to new processes and technologies, not the style and themes Fil embraces, are what Janos proudly takes after his father.

Matching daddy’s achievements

“It’s funny,” Janos says animatedly. “I’ve never consciously tried to emulate or copy my father’s style, but I have tried as much as I could, over the years, to match his accomplishments.” Far for being envious of Fil’s feats, Janos sees it more as forms of positive reinforcement that not only inspire him, but also enable him to take his art to a higher level.

Thus, when Fil received the Benavidez award, one of the highest forms of recognitions UST gives out to its accomplished alumni, Janos also dreamt of and earned the recognition himself much later. When Fil was honored by the Cultural Center of the Philippines as one of its Thirteen Artists awardees some years back, his son was also inspired to produce exceptional work with the hope of one day getting noticed by the country’s premier arts and cultural body. He’s only in his mid-thirties. Give him time and he might one day get it.

“That was how my dad inspired and continues to inspire me,” he says with a hearty chuckle.

Learning, it has often been said, is a two-way street. Since art, Fil believes, is a “continuing process of learning,” he has also learned a thing or two from his son. Although father and son have stuck to their respective styles, this hasn’t stopped them from observing each other’s works and exchanging notes during light moments.

Exchanges

And these exchanges have also involved matters of composition and ways of playing with imagery that an older, more seasoned artist like Fil would have probably dismissed as “off-key” until he saw the quaint beauty of such unusual juxtapositions—for seemingly grotesque human figures interspersed with scenes, say, from a comic strip as well as numerical figures in one frame—in his son’s canvases.

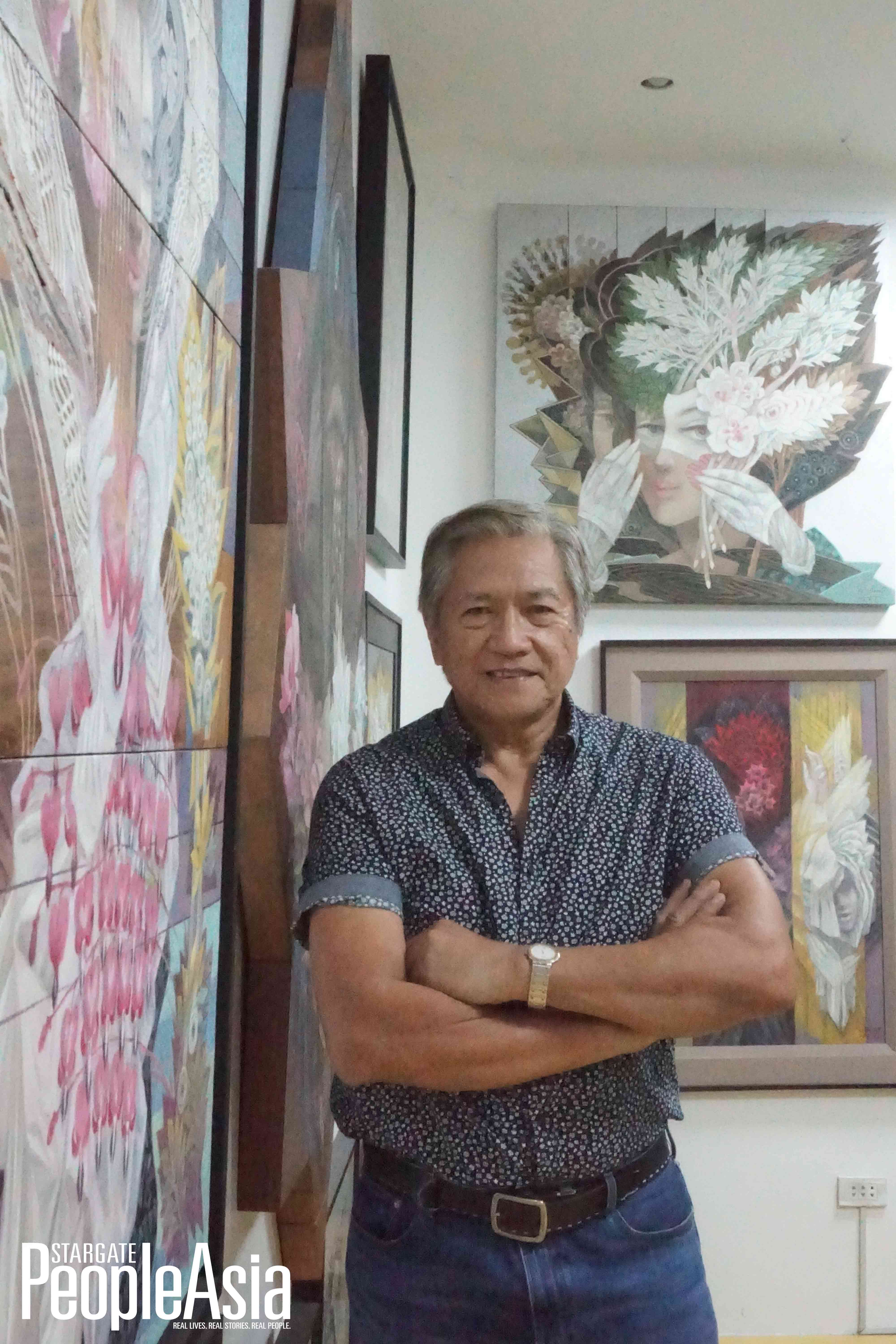

“Like they say, if you want to grow as an artist, don’t stop at being a student. Your attitude as a student should remain. If you already have the attitude of a master, you close the room for further growth. You have effectively closed all avenues to learn and discover new things,” says Fil.

Although Janos’ big brother didn’t end up as a full-time artist, he also possesses that gift that God has so generously bestowed on both Fil and Janos. What his first-born lacked, Fil explains, is the passion to be an artist—“a process as well as a discipline that’s so removed from the cliches we usually see in movies and books.”

His point? Being an artist, no matter how gifted you are, is not as easy as standing in front of the canvas and easel, and coming up with a breathtaking portrait, still life, rural scene or cityscape within five minutes or so. Neither do artists like him only paint when they’re “in the mood.”

“If you wait for that mood to come, chances are you would end up accomplishing very little,” says Fil who, whenever he’s in his studio, spends part of his time conceptualizing and experimenting before sitting down to do the actual work.

The importance of mood

“Yes, I do believe in moods, and its importance” he clarifies. “But it shouldn’t be your prime motivator to produce actual work. You may catch me sometimes sitting down inside my studio doing nothing. But deep inside, my mind is already working, conjuring up images, colors and nuances inside my head.”

He also doesn’t subscribe to the stereotype of the artist going hungry, looking disheveled and leading the unstructured life of a “bohemian” in pursuit of his art. “If that is the case, then it is a choice he has made,” he says, addressing the importance for artists to know their worth as well as the true value of their works.

Both father and son also dabbled as educators, teaching at certain points in their respective careers at their alma mater. Fil also taught at the University of the Philippines and the Philippine School of the Arts in Laguna. These days, both men have decided to impart their knowledge by conducting occasional workshops catered to established artists who want to take their art further through print-making.

Despite the differences in their backgrounds and career paths, Fil and Janos have found certain commonalities as artists. They’ve also decided to work together under one roof, albeit in different areas on the ground floor of the Mexican pueblo-style house they share as a family. The second floor hosts their living quarters, while the third floor leads to a semi-outdoor viewing deck.

Studio with a “ref”

“There was a time when we lived in a house where the refrigerator was in the same area where my father’s studio was,” Janos recalls. “So, whenever my brother and I would get something from the ref, we ended up catching glimpses of dad and his works in progress. We literally grew up seeing how invested he was with his art and profession.”

Such freedom to be was absent while Fil was growing up in Hagonoy, Bulacan. The son of a teacher and a farmer, Fil and his family were far from rich and didn’t have the luxury to experiment and invest in careers that might not pan out or take a long time to bear fruit.

“My mother, a public school teacher, who later became a principal only meant well,” Fil says. Apart from being costly to finance, studying to become an artist offered an iffy future, especially to someone like Fil who was poor and not well-connected.

Most people in rural areas also had a limited idea of what artists could do back then, he says. They thought you’d be consigned to a life painting the artworks that adorn new bancas before they were blessed, or doing giant billboards, images and signages along highways and cinemas, or during town fiestas, decades before the dawn of computer-printed tarpaulins, which have practically decimated such sources of livelihood.

“She was trying to convince me to follow in her footsteps instead by taking up Education. But I couldn’t see myself doing anything else but paint. Instead of giving in, I decided to temporarily stop attending school soon after graduating from high school.” Fil shares.

A life’s journey’s first steps

Three years later, Fil, who made a deal with his older sister for her to help finance his education as soon as she finishes college and becomes a full-pledged teacher, finally began making the first steps into his journey of becoming a trained artist, as he stepped inside the sprawling and postcard-pretty UST campus to begin his formal education.

And he never looked back, making his once doubtful mother, who has since passed on, finally believe in his son’s immense talent and determination, as Fil’s renown in the art world continued to grow through the years.

What about Janos’ achievements as a painter? Does he see it as part of his legacy? “Not at all,” Fil says empathically. “His decision to become a painter has nothing to do with my legacy. I’m just too happy for him that he has found a discipline and source of livelihood that he is passionate about.”

For someone who never had it easy during the beginning, Fil has never once discouraged any of his sons to follow their hearts’ desires. Despite his lax parenting style though, he only had one caveat when they were growing up. And he expected them to follow it: “If you’re not passionate with what you’re doing, you better give it up as soon as possible. Find something else that you’re really passionate about. Otherwise, you’d end up going nowhere.”

Fil and Janos Delacruz, who both occasionally collaborate with Art Lounge Manila, will have their respective shows this July. Fil will be one of the featured artists in the Empty Chair Project at Art Lounge Manila’s gallery at The Podium starting July 1, while Janos will stage his latest solo show starting July 16, also at the same venue.