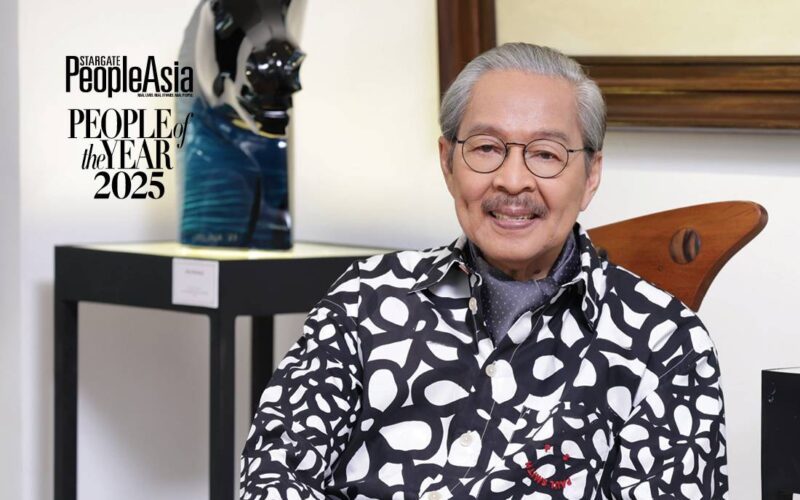

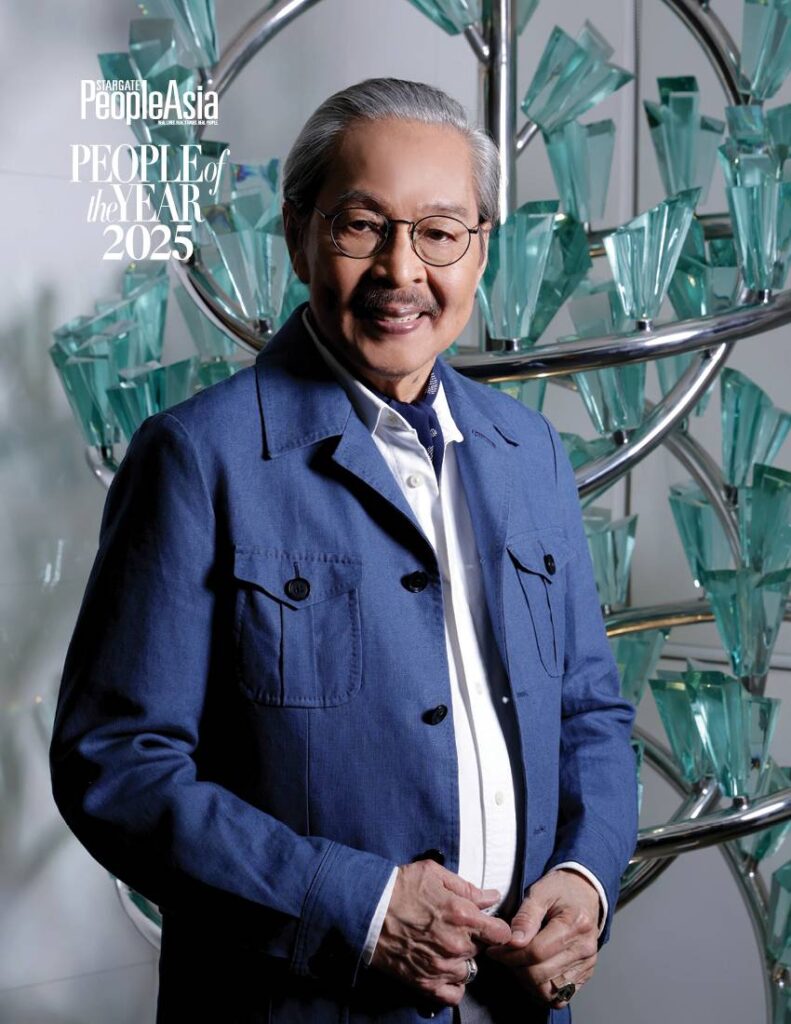

When it comes to revealing hidden forms and shapes within his chosen medium, no artist comes close to this trained architect and devoted family man in bringing out the unique optical and transparent qualities of glass.

By ALEX Y. VERGARA

To a seasoned glass sculptor like Ramon Orlina, who broke ground way back in the early ’70s when, out of necessity, he started to gradually shift from architecture to become a full-time artist, the signature quality of his artworks is as clear as the material he loves to work with.

“The obvious answer would be the medium itself, which is glass,” Orlina, a trained architect, says. “When I sculpt, I always like to maximize the optical and transparent qualities of glass, and use that so-called magic to bring out forms and shapes within the glass.”

He calls this the “fourth dimension,” a state which can only be achieved using a material like glass. Because of the medium’s inherent transparent and optical qualities, which Orlina endeavors to maximize using custom-made tools he developed and perfected over the decades, he doesn’t just focus on the medium’s external form, but also on what can be seen from within.

Drawn to visual arts

Even before he pursued and finished a degree in Architecture at the University of Santo Tomas (UST), Orlina had always been fascinated by the visual arts. And he has the innate talent to go with it, drawing for hours on end as a child, as he copied superhero characters splashed on comic books. His skills came in handy in college when he was exempted from the free-hand drawing course every freshman had to take.

“When I was a child, I would tag along with my mother to Quiapo Church and be awed by the bas-relief sculpture of Napoleon Abueva,” recalls Orlina, who, at 80, remains a sharp and sprightly gentleman with a knack for clothes. “I was so attracted to it. I knew even then that my consciousness of sculpture was awakened.”

But it took a national crisis [soon after martial law was declared in 1972] that directly impacted the construction sector and, by extension, the practice of architecture, for Orlina to gradually embrace art as a full-time profession.

Not long after founding his own architectural firm with a good friend after working for several years with seasoned architect Carlos Arguelles, Orlina started losing his clients no thanks to the economic downturn. In hindsight, he considers such a setback providential.

“With time on my hands, I could do what I loved most — art! So, that was when I started painting. Since I wanted to be different, I painted on glass panes. They became my canvas.”

It was during his initial series of one-man shows in 1975 featuring such paintings on glass that he caught the attention of Victor Lim, president of Republic Glass Corp., then the country’s largest glass manufacturer.

The company invited the young artist to tour its factory and even offered him a scholarship to study glass art anywhere in the world. Although the offer appeared too good to refuse, Orlina declined to accept it after reflecting on it for a week. Instead, he requested Republic Glass to allow him to immerse himself inside its factory by studying the techniques behind glassmaking.

Epiphany

His exposure led him to discover glass cullet, the residual glass from the factory furnace. Upon examining it, Orlina had an epiphany. He had found the material he wanted to work with in throwaway glass.

“I saw tools and equipment in the factory that I later improvised to cut, grind, smoothen and polish these glass blocks. I was able to recycle them and transform them into remarkable works of art,” says Orlina amid some of his best and most iconic works displayed at the private Museo Orlina in Tagaytay City.

Apart from being a showcase of his favorite works, none of which are for sale, Museo Orlina also has ample space to host regular exhibits showcasing the works of other artists.

To say that his initial foray into glass sculpture was difficult and involved a great deal of trial and error is an understatement. Apart from scouring industrial stores looking for equipment he could use to improve his art, he had to learn on his own how to cut, grind, smoothen and polish glass. Sometime later, he graduated from working with cullet as he found glass companies abroad capable of providing him with bigger blocks of glass.

Despite finding a steady source of material, he still has to work around the material in front of him. Put simply, working with a general plan in his head, Orlina allows irregular blocks of glass and not designs drawn on paper to guide him as he chips and grinds away to produce his next masterpiece.

“I’m thankful to have been guided initially by the engineers and workers at Republic Glass,” he says. “Eventually, I had my own studio and fabricated my own machines that would best be used for my process.”

On the home front, he and Malaysian-born wife Lay Ann Lee have been blessed with four children, two of whom — Anna and Michael — followed in their father’s footsteps. Their two other children are Naesa — that’s Asean spelled backwards — and Ningning.

As an aside, Anna, who was present when we visited Museo Orlina, shares with us how her parents met and eventually fell in love. It was in the early ’80s when Orlina, then working on a huge outdoor sculpture in Singapore, had to go to another country after staying for nearly a month in the city state.

He had to refresh, so to speak, his visitor’s visa or risk being questioned as an overstaying alien. To do this, he had to leave Singapore before re-entering it again. Since flying back to the Philippines would have been too cumbersome, Orlina chose instead to make a land trip to neighboring Malaysia.

There, he had the chance to meet up with a Malaysian friend, a woman and proud owner of one of his sculptures. That friend had a roommate who turned out to be Lay Ann, then a young lawyer.

“But before their first encounter, my mom kind of already knew who my dad was through his sculptures. She loves his works,” Anna shares.

Despite their 15-year age difference, love eventually blossomed between Orlina and his much-younger fan. When she and Orlina got married and decided to start a family, Lay Ann decided to quit her law practice in Malaysia for good to join her husband in the Philippines. She has been actively involved in the family enterprise ever since, where she puts her legal training to good use.

Even today, Orlina remains open to new ideas. After Anna, studied abroad, for instance, she brought home with her some techniques she learned at the Corning Museum of Glass. This time, it was her turn to share that knowledge with her father.

Labor-intensive

“Yes, it remains very labor-intensive,” he says, referring to his art. “With my loyal assistants who are like family to me, and now also with my children, the workload can be evened out better. So, I wouldn’t even say that I have slowed down because I love what I’m doing, and I still have dreams that I want to pursue.”

Over the years, Orlina’s recurring themes revolve around family and his Catholic faith — themes, he says, “that are very Filipino.” He’s also drawn to nature, from the country’s majestic mountain ranges to animals, particularly horses and birds.

“They resonate with me because I used to ride horses and also kept birds as pets,” he shares. “The female anatomy has always fascinated artists. I also draw inspiration from my many travels. It’s nice to be able to create a sculpture inspired by a memory or an experience, and have that in my home or in other people’s homes. That’s a very special feeling.

“Also, as time goes by, I have more expertise in my art, and greater confidence. And with art, you know, it is a constant development and discovery. Innovation is important. I’m still getting interesting offers, and I have more means to create bigger and better artwork.”

A car lover as well, Orlina combines his love for it with his passion for the arts through what he describes as “art cars.” He’s building an extension to Museo Orlina to house these beauties.

Some of his favorite works also happen to be some of his biggest works. They include the 10-meter high “QuatroMondial,” which was unveiled in 2011 to mark UST’s quadricentennial celebration, his first big sculpture, the three-ton mural “Paradise Gained” and the 75-ft. glass window in the Singapore Art Museum.

“As for smaller works, there’s ‘Silvery Moon,’ which won me the MR. F. Prize in Toyamura Biennale Japan and ‘Basketball Mi Mundo,’ which won me first prize in Madrid. Other works that are very special to me are the ones that are named after my children. The ‘Ningning’ series is the most famous one,” he adds.

As one of the country’s most celebrated and most prolific sculptors for nearly five decades now, where does Ramon Orlina plan to take his art?

“I want to be able to follow my passion projects, like the art cars,” he says in conclusion. “I also want to collaborate more with my children since they are sculptors, too. And I’d like to see more sculptors working on glass and having their own take on it. I am heartened to see more artists pursuing this seriously, and I want to encourage them. And my word to them is to have artistic integrity and be true to yourself.”

Photography by RENJIE TOLENTINO

Art direction by DEXTER FRANCIS DE VERA

Grooming by FRANCINE QUIRINO

Shot on location at Museo Orlina, Tagaytay City