By Joanne Rae M. Ramirez

“One never forgets.”

Never, never, in my wildest dreams did I think that the principal when I was in high school at the Assumption Convent, San Lorenzo, the nun in the purple habit who would strum the guitar during Mass and give the most compelling of talks — and the most engaging of jokes — was not just a rape victim but also a victim of incest!

To me, Carmen “Pinky” Valdes, then known to us as “Sister Jude,” looked like Princess Diana. She still does. She always held me in thrall whenever she spoke, and especially when she sang. She was always news.

When she left the convent, she was news.

When she became the first lay person to become president of Assumption College, she, again, was news.

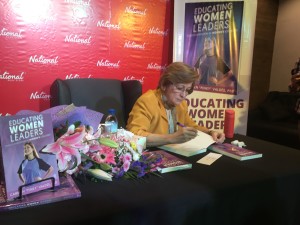

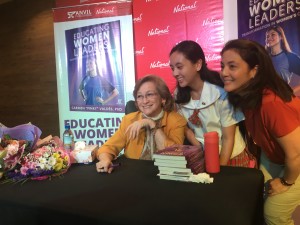

But this woman who always blazes trails and shocks and awes people, then dropped the biggest of all her bombshells when she launched a book last week that detailed her deepest secret without shame. In her newest book, Educating Women Leaders: Transformation in Women’s Colleges (available in National Book Store Glorietta 1), she bared her past in a chapter titled, “What was Missing?” In that chapter, she detailed the points that are either missing or inadequately considered in the education of young women. The fifth point there was “What nobody wants to talk about — incest, sexual, abuse and domestic violence.”

Then in a sub-chapter titled “I know from experience,” she told her story.

***

“It was the year of my first communion. We lived in a compound in Metro Manila. I was in second grade. My cousin was a teenager. This is what I clearly remember. He took me up the staircase to his room in the big house…As he led me to his house, my heart started beating faster. Somehow, I knew things were not right. He opened the door to his room. I remember the bed and the words he said. He made me lie down. I need not spell out the rest.”

Pinky recalls that when it was over, he looked at the sheets. She remembers the word, “blood.”

Now, she knows why. Unfortunately, her experience wasn’t a one-afternoon stand for her abuser. “Once or maybe twice, he brought another cousin about his age. I can still smell them. Just the memory of the scent turns my stomach. One never forgets.”

Pinky also experienced abuse in the hands of a babysitter, her “Tita Sally” who burned her bottom with a burning match stick when she wet her parents’ bed.

But the abuse did not end there.

After second grade, Pinky’s family left Manila for California. One day, her father, a La Salle boy through and through (“the type who carried a rosary in his pocket to his dying day”), invited one of his teachers, an American Brother, to their home.

“The Brother won me over with his magic tricks,” says Pinky. But what was to follow wasn’t magic at all. During one of the Brother’s frequent visits to the Valdes home, he would let Pinky sit on his lap, and “then he would begin to touch me.”

One day, her mother chanced upon a scene that shocked her. When she asked Pinky if the Brother indeed touched her, the little girl, typical of an abused child, lied and said, “No.”

It was only when her mother asked her a second time, and assured Pinky that what transpired was not her fault, that she tearfully admitted that yes, she was touched.

But then her mother told Pinky something that was just as jolting: “You know, Pinky, priests and brothers get very lonely, so sometimes they do things they should not do.”

To this day, Pinky, who holds two master’s degrees in educational management from La Salle and another in Theology from the University of San Francisco, and a doctorate in Philosophy from UC Berkeley, is not sure whether her mother was being compassionate or was simply in denial.

“Between my cousin, Tita Sally and the Brother, my childhood was lost and left me with unbearable wounds. It has taken many, many years for the wounds to heal.”

Perhaps, the reason Pinky delves into the issue of the inner scars of a woman is to posit the fact that our wounds can save others — just like Jesus Christ’s wounds have.

When Pinky was working on her master’s in Theology, a professor, Sister Mary Neil, talked to the class about healing a child who is a victim of abusive adults. One woman in the class suddenly cried, “I was a victim of incest. I am sure none of you know what this is like.”

Pinky looked at her and said, “I do.” The woman stopped crying.

There was a man in the group and tearfully, he held both Pinky’s hands and said, “Pinky, I am a priest. In the name of the Catholic Church and of priests and brothers everywhere, I apologize to you. The Church owes you a profound apology…I am deeply sorry.”

For Pinky, who was also awarded the Loyola Professorial Chair in Theology by the Ateneo de Manila University, her childhood trauma has given her an experiential understanding of how “broken many of us are and how badly we need healing.”

“I am not talking here about just the victim, but the abuser as well because he or she, too, is a broken person.”

Pinky, who in fact went to La Salle for her master’s, has forgiven her abusers. “I forgave them, a long time ago, and that is why I have been able to move on.”

***

Last week, Dr. Pinky Valdes, now the first lay president of the Assumption College, broke her vow of silence about being raped by a teenaged cousin when she was six years old, and other abuses.

Now 74, Pinky talked about the abuse when she launched her book Educating Women Leaders: Transformation in Women’s Colleges in front of the nuns of the Religious of the Assumption without shame or fear.

Why only now? I asked her in a one-on-one interview at the Assumption, not far from the classrooms where she would teach us.

“Because in our day we didn’t talk about those things,” she says. But now, wherever she goes, both men and women stop her to salute her courage.

Why did she do it?

“The reason why I spoke is to give other people the courage to speak up. I’m against extrajudicial killings, I’m against violence but I cannot ask you to go out and protest if I’m not going to step forward myself. I can’t say, ‘You go tell your parents!’ if you are abused, but I am in the shadows and I’m not saying anything. I have to be the first to show this is the way you handle it, because the best friend of abusers is silence. And all people who are abused, even domestic violence and physical violence, their best friend is silence. Because if the person who was abused — the wife or a girl, some of these girls have been abused by their boyfriends because they told us, they were not beaten up but they were slapped — the first thing that happens, 80 or 90 percent of the time, you freeze. Some people run right away, some people get really mad, but 80 percent of society, look at all those movie stars, they froze.”

Pinky, who was called “La Rubia” (the Blonde) by friends and family alike because of her golden hair, was raped at age six by her teenaged cousin, who lived in the house next to theirs. Traumatized by the experience, she wet her parents’ bed and her caregiver “Tita Sally” lit a match under her bottom while she sat over an orinola. When she was older, in the US, she was molested by a La Salle Brother, her dad’s favorite teacher.

Despite the string of abuses, and the fact that she had no one to turn to, Pinky didn’t cave in. She stood tall and straight.

“Spirituality is what got me across,” she declares. “Because spirituality is what gives you depth.” She tried to find meaning in life. It also helped that she had loving parents, and in their care, she found a safe harbor. Except at that time six decades ago, she just couldn’t tell them about what her cousin did to her.

During family reunions, she would see her cousin looking her way. But she would look away.

Then about 10 years ago, when she decided to write the book, she asked her friend Anna Valdes Lim if she should include that painful episode in her life in the book she was planning to write.

Anna then told her, “You have to, otherwise the secret goes on forever.”

Ever since the book was launched, Pinky says she got many text messages saying, “Me, too.”

***

But has she forgiven her cousin?

To my utter surprise, she forgave the man who robbed her of her childhood, “very easily.”

She wrote her cousin when she was in her sixties and he, nearing his eighties. She let it all out, the hurt and the feelings of betrayal. “I don’t know how you feel,” she wrote him, “but I forgive you anyway.”

He wrote her back. It was a short letter with a bold message, “Thank you very much. I have lived with guilt all my life. All these years I’ve been wanting to apologize but I didn’t know how, and I’ve been wanting to approach you.” Pinky realizes that’s why he kept on looking at her.

He died not long after.

***

After her traumatic experiences, Pinky turned to something that would give her a high. Not drugs, but a spiritual high. “Let’s say that the rape never happened to me, I still would’ve had this life. The dimension that it added was that from a very early age, I was looking for meaning. There has to be something there.”

It also gave her a third eye that made her see others who were also in pain. “The experience made me empathetic and very understanding of others’ pain.”

I asked her if she felt her revelation that she is a rape victim has diminished her stature as president of Assumption College.

“If you’re in a position of power, you cannot have been raped because that ruins the power? It’s kind of strange, isn’t it? I knew that those reactions would happen. But I said that’s par for the course and let the chips fall where they may. If you think that a person in a high position should be untouched by the world, unscarred by the world, and that’s your image of power, you have a lot of thinking to do because that’s not what it is. What makes a person strong is to grow through pain and transcend it. It can be cancer, it can be sexual abuse, it can be rejection, it can be ‘I’m not pretty as my sister,’ or ‘I’m not as rich as you are,’ ‘I’m not as educated as you are.’ All of them fall under the same category. It’s not just sexual abuse.”

She tells me the Assumption nuns were “very supportive” of her coming out.

“The aim of education in the Assumption is to set a person free and to allow the good to break though the ‘rock’ that imprisons it and bring it into the light of truth and faith, where it can blossom and shed its radiance. And by setting the person free, she can be an instrument or channel of transformation, of life in the world,” says Sister Sheryl Reyes, the provincial superior for the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam.

“The people who can lead are the ones who have been to the trenches. You can’t stay in the trenches because then you’ve just allowed the trenches to swallow you. You have to pull yourself together, you have to transcend it and say ‘Now, what can I do to give back to society?’ You go up and you give it back. It’s not the end of my life. You go back to that pain to get the light.

“My book is about educating women. I put my story because I wanted to reach teachers, parents and girls to help them how to deal with these traumatic events and make them transformative,” Pinky explains.

Pinky left the convent more than 30 years ago but her spirituality has not diminished. She says that whether a pearl is in an oyster’s shell or in the sand or mounted on a ring, it is still a pearl.

So now you see, it is more than just Pinky’s natural golden blonde hair that makes her shine.

Despite all her hurts and pains, or because of all her hurts and pains, she shines.

This peace was originally published in two parts as “My HS principal at the Assumption, then a nun, was a rape victim” and “Raped at 6, she ‘very easily’ forgave her attacker for robbing her of her childhood” in the Feb. 6, 2018 and Feb. 8, 2018 editions of The Philippine STAR respectively. Educating Women Leaders: Transformation in Women’s Colleges by Pinky Valdes, PhD is available at National Book Store.